For the meat-alternatives industry, business has been booming lately. One of the meat-alternative options that is becoming more accessible throughout different grocery stores is tempeh (or tempe – in Bahasa Indonesia). If you haven’t seen one around, tempeh looks like a network of soybeans that is held together by clouds of white fluff – mycelium – as a result of fermentation. It has a nutty taste that can readily absorb flavor from other ingredients/sauce that you cook it with. While tempeh may be relatively new in the United States, it is considered one of the staple foods in my home country – Indonesia – where it serves as an affordable source of protein, and has been enjoyed by Indonesians for many generations. The fermentation process is not only responsible for giving tempeh its final look, but also enhancing tempeh’s nutritional values compared to its raw ingredients (soybeans).

Fermentation is an event whereby microorganisms (e.g. yeast, bacteria) are used to chemically breakdown a substance. Usually, the microorganisms will break down the available carbohydrate (e.g. starch or sugar) into alcohol or acid. Historically, in food science, fermentation has been used as a way to preserve food, get a desirable flavor, enhance nutrients and reduce toxicity of raw ingredients. Fermented food is seen as a safe, inexpensive, nutritious food source especially in developing countries if the technique is done properly.

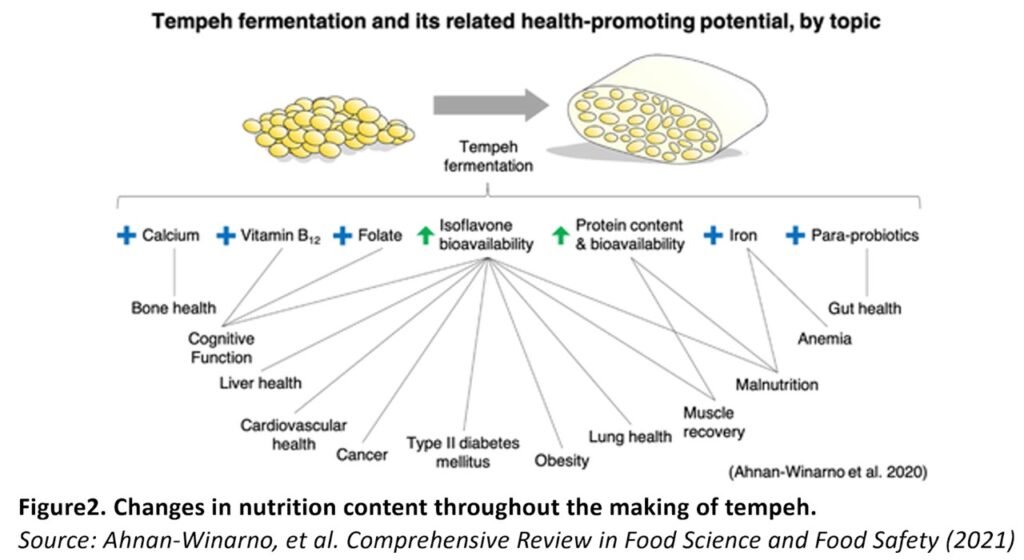

For tempeh, the fermentation process happens as soybeans and Rhizopus oligosporus (R. oligosporus) fungus are mixed. However, the preparation steps prior to this are important to ensure optimal fermentation conditions (Figure 1). Cleaning the soybeans is done to remove dirt, damaged beans and other foreign matters. Dehulling is needed as R. oligosporus can’t grow on whole soybeans with hulls. During the soaking process in water, soybeans undergo natural microbial acidification. This lowering in pH enables the mold in subsequent steps to grow while suppressing bacterial growth. Alternatively, a small amount of lactic acid or acetic acid is sometimes added during the soaking process to prevent microbial spoilage. Boiling is done to partially cook the soybean and eliminate contaminating bacteria, to break down antinutritional factors, and to release nutrients that will help the mold to grow. Draining and cooling are needed as excess water can spoil the tempeh and decrease its shelf life.

For tempeh, the fermentation process happens as soybeans and Rhizopus oligosporus (R. oligosporus) fungus are mixed. However, the preparation steps prior to this are important to ensure optimal fermentation conditions (Figure 1). Cleaning the soybeans is done to remove dirt, damaged beans and other foreign matters. Dehulling is needed as R. oligosporus can’t grow on whole soybeans with hulls. During the soaking process in water, soybeans undergo natural microbial acidification. This lowering in pH enables the mold in subsequent steps to grow while suppressing bacterial growth. Alternatively, a small amount of lactic acid or acetic acid is sometimes added during the soaking process to prevent microbial spoilage. Boiling is done to partially cook the soybean and eliminate contaminating bacteria, to break down antinutritional factors, and to release nutrients that will help the mold to grow. Draining and cooling are needed as excess water can spoil the tempeh and decrease its shelf life.

Finally, after all those steps are done, the mixture is traditionally wrapped in banana leaves to keep the beans moist and to allow gas exchange to occur. If you use a DIY tempeh starter kit that is available commercially, a plastic bag can also be used as a fermentation container. What matters is that the wrapping material allows for gaseous exchange to occur as oxygen is needed for the mold’s growth. The soybeans and R.oligosporus mixture is then kept cozy in a temperature that ranges from 25°C to 37°C for up to 48 hours, with higher temperatures requiring less incubation time. Humidity needs to be monitored throughout this time as dried out beans could stop the mold growth and consequently increase pathogenic bacterial growth instead.

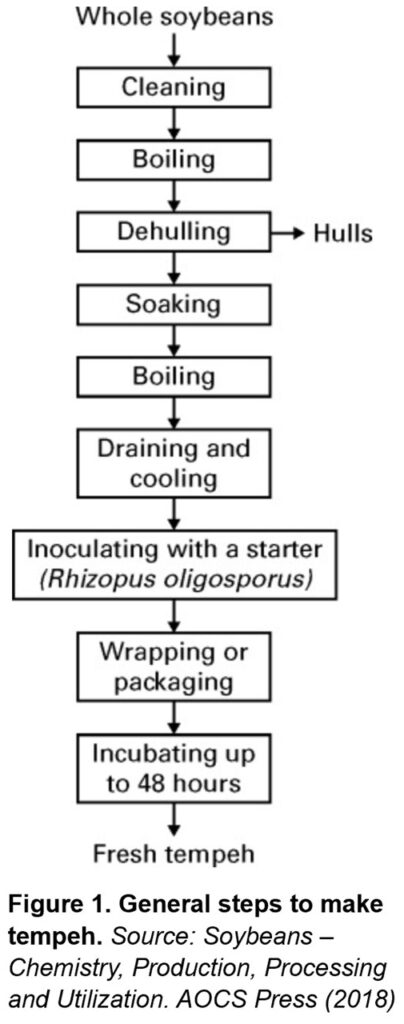

After 48 hours, not only does the fermentation process change the whole appearance of the soybeans into this glorious soybean cake, but it also transforms the nutritional content of the soybeans (Figure 2).

Soybeans contain high levels of α-galactosides of sucrose, which can cause one to feel gassy. This sugar is removed through the soaking, cooking, and fermentation process as R. oligosporus uses it as a source of carbon and energy. Fermentation also decreases soy’s high phytic acid level. Phytic acid can hinder mineral absorption, so its reduction consequently allows soy minerals (e.g. calcium, zinc, and iron) to be absorbed by the body more readily.

Tempeh is just one of the many examples whereby mold can be used to transform the look and nutrient content of one food into another. Other foods that also use the benefit of the fermentation process are cheese, kimchi, and kefir.

Although tempeh is not as popular as its soybean-based cousin (tofu) yet, it has certainly gained the interest of many plant-based food companies. There are increasing numbers of recipes out there, but you can also start with this simple recipe I grew up with: simply soak sliced tempeh in water that has been seasoned with salt and (many) crushed garlic cloves before frying them. Enjoy it as a snack or as a side dish! Other traditional Indonesian tempeh recipes to try are: tempeh manis (sweet soy tempeh), kering tempeh (crispy tempeh), keripik tempeh (crispy fried tempeh), and sambal goreng tempeh (chili-fried tempeh).

Peer edited by Corban Murphey and Rachel Haake