Have you ever cooked something that smells mouthwateringly good and tastes even better? What about a dish that smells foul and makes your nose scrunch in disgust? Our experience with food is mediated by a cacophony of tastes and smells that stimulate our senses. What causes these stimuli, and how are we able to perceive them?

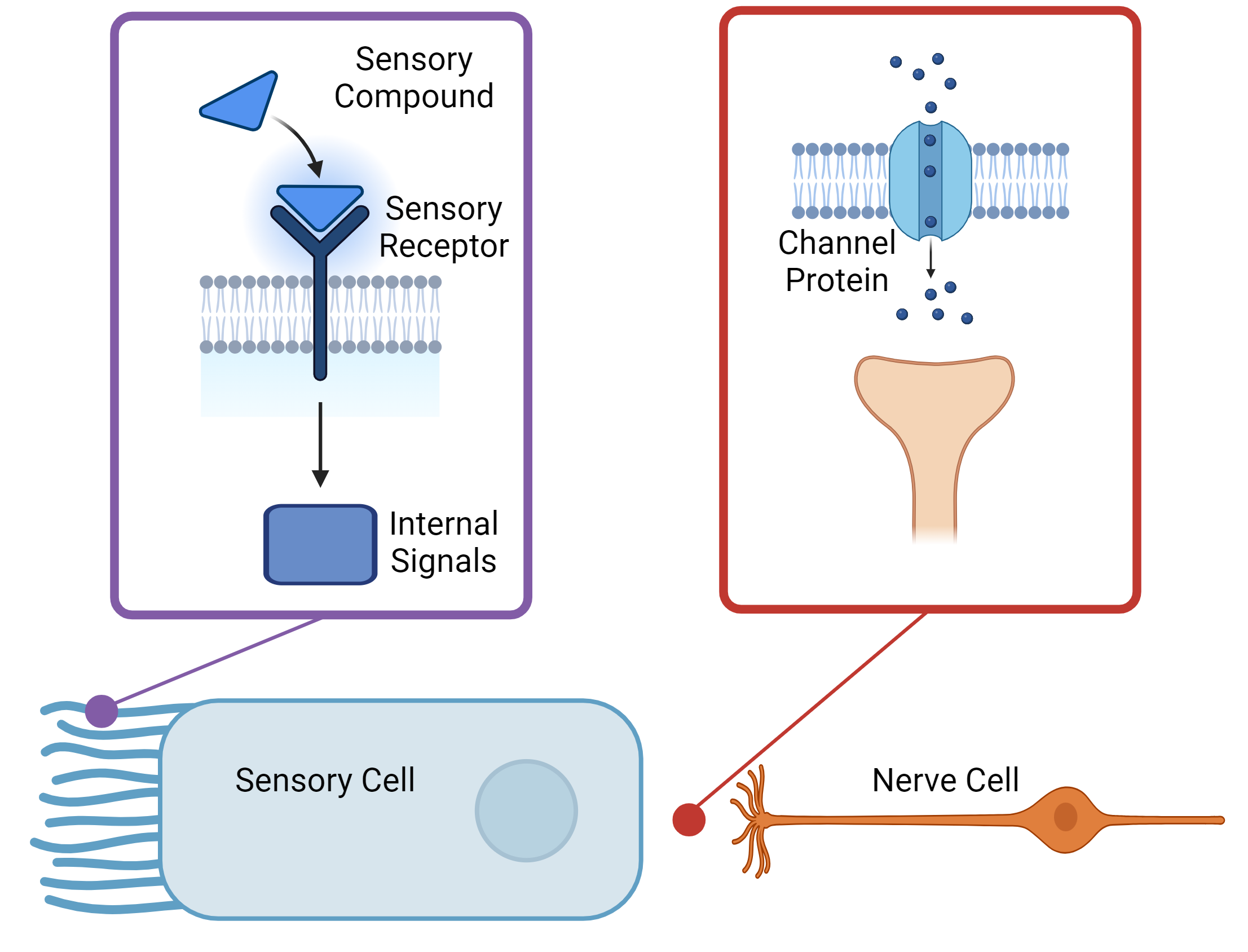

Food is made up of small molecules that we can sense thanks to specialized cells in our taste buds and nostrils. A huge variety of molecules act as signals for a particular taste or scent. Generally, “receptor” proteins on the cell surface recognize these molecules outside of the cell and translate it to proteins inside the cell. The internal proteins play a game of telephone, passing that signal along the line until it reaches a “channel” protein on the other end of the cell surface. The channel releases a new set of signals outside of the cell that are recognized by nearby nerve cells, which transmit the message to the brain.

The “sapid” molecules that create taste signals are recognized by two major types of receptors on our taste buds. The “Type 1” receptors translate sweet signals and the “Type 2” receptors translate bitter molecules. Both families consist of dozens of receptors, and each receptor is specific to a particular sweet or bitter molecule. Unsurprisingly, sweet receptors identify different sugars. On the other hand, bitter compounds can have a wide variety of chemical structures, and scientists have created ways to predict if a molecule will have a bitter flavor.

New taste receptors are still being discovered, including those that translate molecular signals for umami, sour, salt, and fat. Recently, scientists discovered receptors that identify temperature using capsaicin from spicy peppers and menthol from mint, resulting in a 2021 Nobel Prize. Beyond the dozens of different taste compounds and receptors, the flavor of our food is amplified by visuals, temperature, mechanical feel, and smell.

Similarly to taste receptors on our tongue, our nose has special cells with olfactory receptors. When you smell your food, you’re inhaling vaporized odor molecules that are recognized by the receptors. This process also happens when you chew your food, leading to a mixture of taste and odor signals that help determine the flavor of your meal. The 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for research that established our fundamental understanding of olfactory senses. Scientists found that each olfactory cell only has one kind of receptor that recognizes a limited set of odor molecules, and our nostrils house a multitude of cells to identify a wide variety of smells. Amazingly, we have hundreds of different olfactory receptors to recognize over 10,000 different odors. Different patterns of molecules and receptors merge to generate a smell “pattern” for us to recognize and remember.

The mechanisms controlling our senses are extraordinarily complex. We’re able to process a myriad of taste and odor compounds that will unconsciously draw us in or push us away. With these senses, our brains build memories of particular tastes and smells that inform our relationships with food.

Peer Editor: Caroline Yu

Featured Image: Illustration by Demi Sakelliou is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.