I watched the man at the table next to me begin to sweat profusely. I was enjoying wings with my family, and he had clearly chosen one of the spicier sauces. Why was he doing this to himself?

According to the US Department of Agriculture, the average American eats over 7 pounds of chilies a year. What is it that attracts people, like the man in the wings restaurant, to the burn of eating chilies? It is possible that you feel the same reaction eating chilies that you do riding a roller coaster? Yes, it is surprisingly similar! You get the same sense of anticipation, heart beat increase, then a rush of adrenaline and endorphins.

It has to do with the receptors that send signals to your brain, telling you that you are eating something hot. Your papillae, located on the tongue, are the receptors that detect spice, but these receptors also are activated by thermal stimuli. When you eat a chile pepper, your brain thinks your tongue is literally on fire, hence the sweating that ensues. With enough heat, your body begins to produce adrenaline and your heart pumps faster. Then, to help block the pain, your body produces endorphins. Just like riding a roller coaster, this is what makes peppers so exciting to consume.

Many people enjoy the effects of spice, but why do some people max out with the mildest jalapeno, while others enjoy much hotter peppers? There is no solid research yet to indicate that genetic differences could play a role in our tolerance to spice. However, there is plenty of data suggesting that the receptors on our tongues lose sensitivity under prolonged exposure to the same stimulus. So the more spice our capsaicin receptors are exposed to over time, the less we feel the burn. Meaning, if I had eaten a diet rich in spicy food as a child, I would be less sensitive to the burn today.

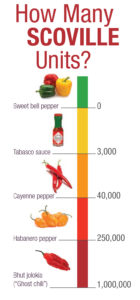

Capsaicin (pronounced cap-SAY-iss-in), the chemical compound produced by the chile that gives them their heat, can be detected by human taste buds in solutions of ten parts per million. The spice of a chile is measured in Scoville Heat Units (SHU). Wilbur Scoville, a chemist at Parke-Davis Pharmaceutical Company in Detroit, developed the SHU scale in 1912 by diluting chile pepper extract in sugar water. A panel of tasters would then rate the spice in the dilutions until the burn was no longer detectable. Today, we no longer rely on a panel of human tasters to determine SHU, but instead we can use high-pressure liquid chromatography, a computerized method that can determine the capsaicin concentration very precisely. This method is still not perfect though, as it may ignore other chemicals that are enhancing how spicy we perceive the pepper. Today, Chile peppers range in heat from 0 SHU (bell pepper) to over 1,000,000 SHU (Bhut Jolokia pepper). A typical jalapeno ranges between 2,500-5,000 SHU.

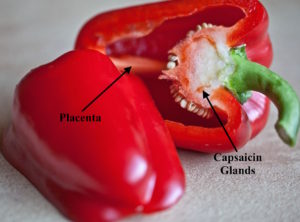

When making dishes with chile peppers, do you carefully discard the seeds thinking you are avoiding the spice? If so, you have been woefully misguided. The capsaicin is not in the seeds, but is actually produced in the capsaicin glands, which are in the bulb right underneath the stem and stored in the chile’s placenta, the lighter colored rib running down the inside of the pepper. The seeds can occasionally absorb some of the heat because of their proximity to the area where the capsaicin is produced, but they are not the spicy part of the pepper.

Humans have conserved the capsaicin receptors presumably to warn us that whatever we’ve put in our mouths is bad news. However, capsaicin and other hot foods won’t damage your tongue – so eat as much as you want and enjoy the burn!

Peer edited by Mikayla Armstrong.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: