Growing up in Indonesia, I was blessed with plenty of sun, warm weather, tropical fruits, and friendly neighbors, but I also had to contend with frequent mosquito visitors. Aedes aegypti (Ae. aegypti) mosquitoes, in particular, are mosquitoes of concern since they can transmit diseases from an infected person to others, with dengue being the most prevalent. Aedes mosquitoes live throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Consequently, dengue is prevalent around this area since it is transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes.

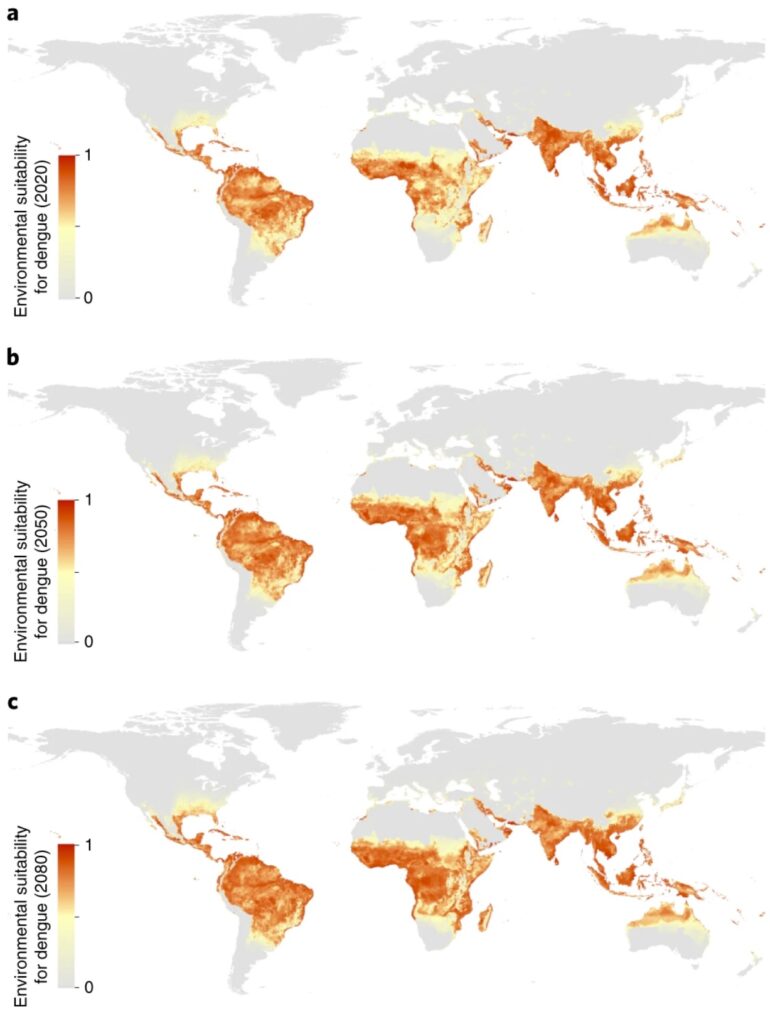

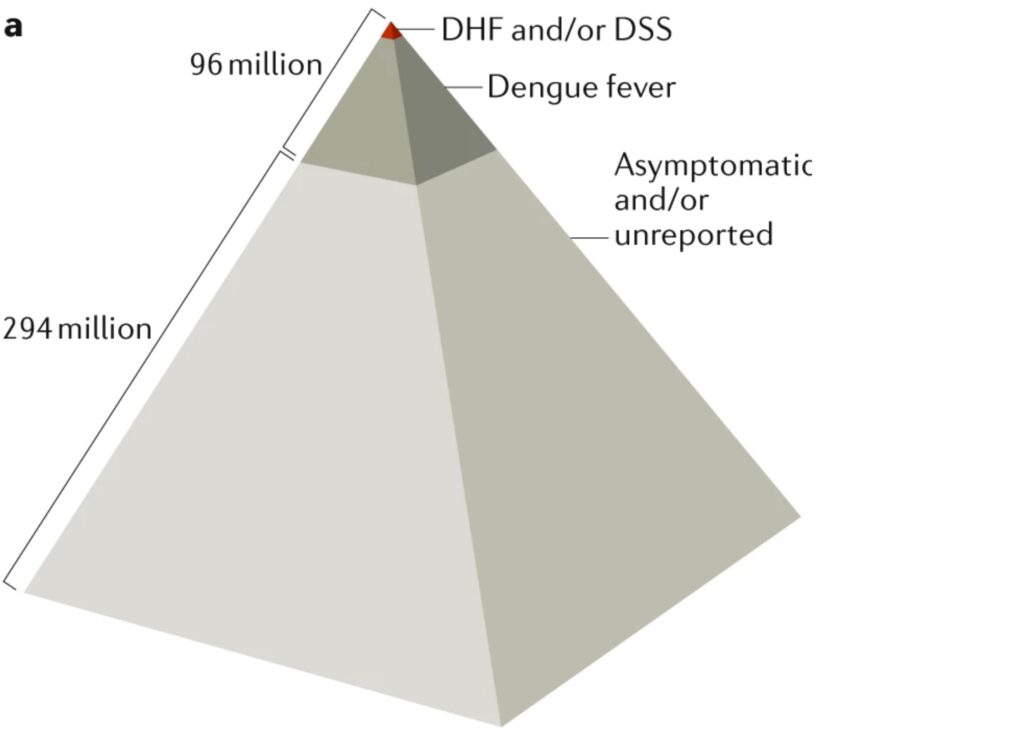

Dengue is a disease that is caused by 4 different dengue viruses. It is estimated that 4 billion people live in areas with a risk of dengue, and this number is expected to increase due to climate change (Fig. 1). Around 390 million people are infected with dengue each year. While most cases are asymptomatic, some people experience severe dengue cases which include dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS) (Fig. 2). These severe cases are characterized by plasma leakage, internal bleeding, nose and/or gum bleeding and organ impairment, which can be deadly if not treated in a timely manner.

Figure 1. Areas that are conducive for dengue transmission over the years. Range 0-1, with 0=non-conducive to 1=conducive for dengue transmission. Source: Messina, et al. Nature microbiology (2019)

Figure 2. Although most dengue cases are asymptomatic, around 20% of those who are infected experience symptoms ranging from dengue fever to fatal cases, such as dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS). Source: St. John, Rathore, Nature immunology (2019)

Currently, there are no specific treatments for dengue. Since there are four types of dengue virus, it has been a challenge to make an effective dengue vaccine that elicits equal responses to all four dengue viruses. In dengue field, someone who never had dengue infection before is called a dengue-naive individual. When dengue-naive individuals receive the current dengue vaccine, imbalance response to any of the four attenuated dengue viruses in the vaccine poses them to a greater risk of developing severe dengue if they get infected with dengue in real life. Hence, the current vaccine is only recommended for people who have had previous dengue infection.

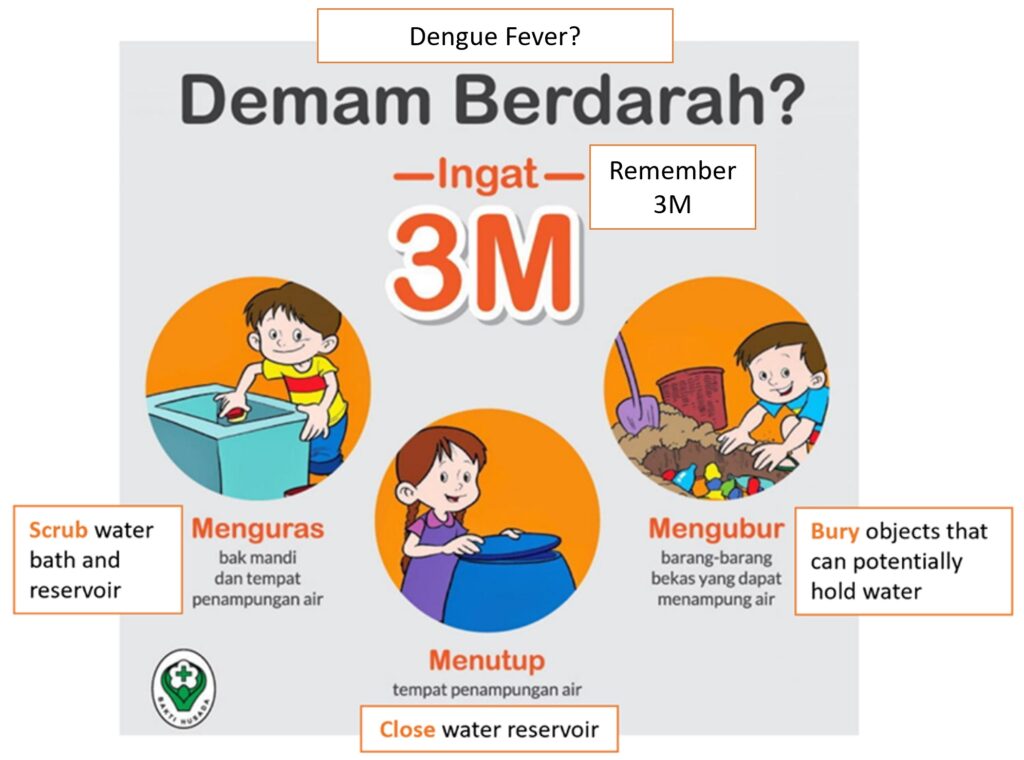

Due to the lack of specific dengue treatment and subpar dengue vaccine results in dengue-naive individuals, efforts to prevent dengue transmission are crucial to minimize the number of dengue cases. One of the preventative efforts that I grew up with was making sure that mosquito breeding ground was kept to a minimum. Pamphlet of dengue prevention campaigns to prevent mosquitoes breeding grounds from thriving and spreading (Fig. 3) is commonly found throughout different neighborhoods in Indonesia, and local governments regularly check for the presence of mosquito breeding ground in the neighborhood every few months.

Figure 3. Modified figure on dengue fever prevention from Indonesia’s Ministry of Health

Figure 3. Modified figure on dengue fever prevention from Indonesia’s Ministry of Health

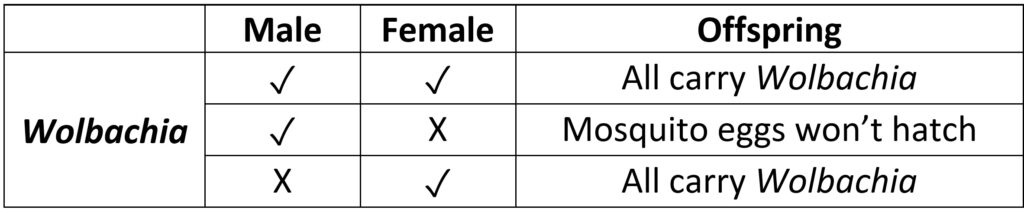

In the past few years, scientists have been looking for ways to reduce dengue transmission in an entirely new way – using the bacteria Wolbachia. Wolbachia affect the reproductive system of their host to ensure their own survival and spread. In mosquitoes, Wolbachia are passed on from one generation to the next through mosquito’s eggs (Table 1). Over several years, the number of Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes will increase following this route of infection.

Table 1. The resulting offspring from different combination of male and female mosquitoes who are infected/non-infected with Wolbachia.

In nature, Ae. aegypti mosquito does not get infected by Wolbachia; thus, when dengue virus infects Ae. aegypti, it is able to replicate freely inside the mosquito. Scientists overcome this challenge by injecting Wolbachia into mosquito eggs. Consequently, these hatched mosquitoes will carry Wolbachia and can pass the bacteria to its offspring. When this Wolbachia-positive mosquito feeds on dengue-infected humans, the existing Wolbachia in the mosquito will compete with dengue virus, consequently making it harder for the virus to replicate. The resulting low viral load in the mosquito reduces the possibility for the dengue virus to be transmitted to the next person that the mosquito feeds on.

Programs that implement this approach are taking place across the world, including The World Mosquito Program with sites across 12 countries (including Indonesia and Brazil), Project Wolbachia in Singapore, and Prevent Arboviruses (COPA) project in Puerto Rico which is a collaboration between CDC and Puerto Rico Vector Control Unit. Generally, the programs work with the local government and community to host Wolbachia-infected mosquito eggs or release Wolbachia-mosquitoes in the area over a period of time. A decrease in dengue cases were observed across the different study sites throughout the years after the initial release of Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes, such as in Singapore, Indonesia, and Brazil.

The long-term benefits of this new approach remain to be seen. To implement this method on a larger scale, one of the major hindrances is the cost of producing Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes, especially for low- and middle-income countries. However, based on the promising initial results, this approach could potentially help protect the four billion people who live in areas with high risk of mosquito-borne diseases. Furthermore, the use of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes could potentially reduce the transmission of other diseases that are also transmitted by Ae. aegypti, such as Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever.

Peer editors: Rami Major and Sophie Kennedy