Likhaan, an acronym for “Linangan ng Kababaihan” meaning “a place for the development of women.” This week on March 8th, International Women’s Day (IWD) gives us the opportunity to celebrate women’s achievements and take action toward gender parity as the United Nations calls all of us to #EmbraceEquity. IWD has been observed since 1910, and over the past 113 years, women have gained greater equality in legislative rights and increased visibility in professions once dominated by men. However, there is much to be done with respect to the gender wage gap and the less commonly discussed gender health gap. Just last year on the evening of May 2, 2022, a leaked draft of a United States Supreme Court opinion to overturn Roe V Wade, which legalized abortion across the nation, raised the question of the implications on the health, safety, and well-being of women across America and the globe. When Roe V Wade fell on June 24, 2022, it was about more than just abortion—it was about the fundamental right of a woman or girl to make autonomous decisions about her own body with an aspect of that being her reproductive functions. Without recognizing that autonomy, how will society see any choices a woman makes about her health and life decisions as legitimate? Although sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is a significant part of women’s health, the definition of being a woman—in identity and personhood—comes in multiples that cannot merely be valued by the ability to multiply.

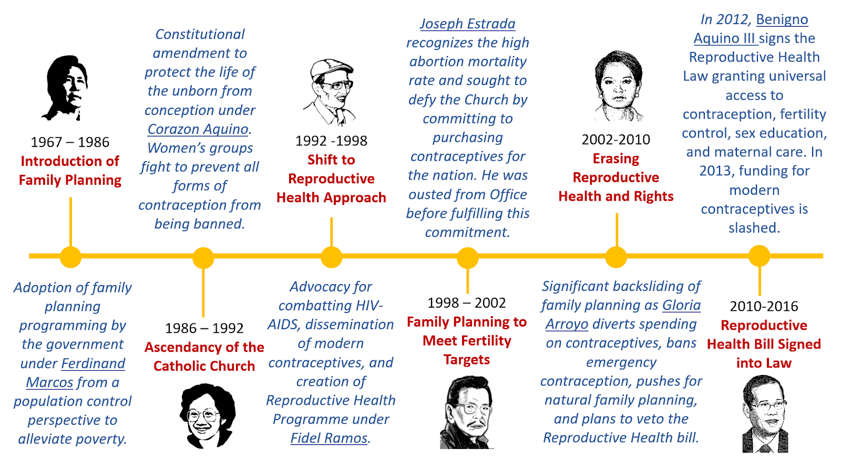

Witnessing millions of women across the United States be denied their right to bodily autonomy led me to reflect on the status of abortion rights and women’s health in my home country, the Philippines. Considering that we were once colonized by America, the overturning of this policy still has an impact on the perceived value of women’s health and rights even oceans away. As a predominantly Catholic nation, the Philippines has criminalized abortion for over a century since the Penal Code of 1870 under Spanish colonial rule and the Revised Penal Code passed in 1930 under US occupation. Without access to safe abortions, Filipino women risk their lives enduring unsafe abortions or high-risk pregnancies. In 2008, the criminalization of abortions resulted in the deaths of at least 1,000 women and complications for 90,000 more including hemorrhaging, sepsis, peritonitis, and trauma to the cervix, vagina, uterus, and abdominal organs. Over the years, progress in the protection of women’s health and rights has wavered depending on the Administration (Figure 1). For decades, a cycle of one step forward and three steps back would repeat until the Reproductive Health (RH) Law was passed in 2012, which declared universal and free access to contraception, fertility control, sex education, and maternal care. The RH Law has led to strides in improved SRH with 7.9 users of modern contraception reported in 2022, an adolescent birth rate of 25% (250 per 1,000 women) as compared to 47% in 2017, and the prevention of about 2 million unintended pregnancies. However, continued challenges of the law by the Catholic Church and disrupted access to care and programming during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the Philippines falling short of its obligations to improve SRH services.

Even with such barriers to SRH services, champions of women’s health have been working to improve the state of women’s health and equitable access to services in the Philippines, community by community. Founded in 1995, Likhaan is an NGO in the Philippines that “aims to achieve health and equality, especially for women of poor and disadvantaged groups.” Experiencing the hardship of the Marcos dictatorship and witnessing violence against women in the Philippines during her medical school training inspired Dr. Junice Melgar to co-found Likhaan, of which she is the acting Executive Director. In its early beginnings, the organization hosted community-based women’s clinics screening for hypertension, tuberculosis, and other general health concerns. Over time, Likhaan recognized an increasing demand for reproductive health and family planning services and shifted its focus while organizing and training women in slum areas as community health workers and advocates. Likhaan was instrumental in advocating for the Philippines Reproductive Health Bill which was signed into the RH Law. Their work continues to reduce maternal deaths, expand family planning and contraception accessibility, and improve health education for youth (Image 1).

Though Dr. Melgar is a well-renowned pioneer for SRH in the Philippines, she is quick to point out that “women’s health is broader than SRH although sexual and reproductive health is a big part of it.” When asked why the maternal mortality rate in the Philippines has not significantly declined since 1990 despite advances in technology, improvements in medicine, and increased funding for healthcare, she responded by stating that what has not changed since 1990 is the gender appreciation of women. Technology cannot resolve population health issues if we continuously fail to invest resources in half of the population, particularly those who are poor and thus subject to greater health disparities.

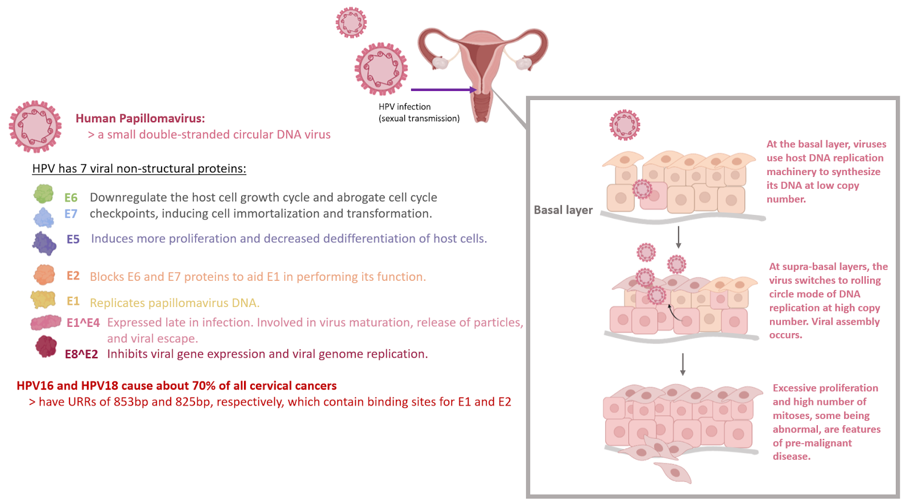

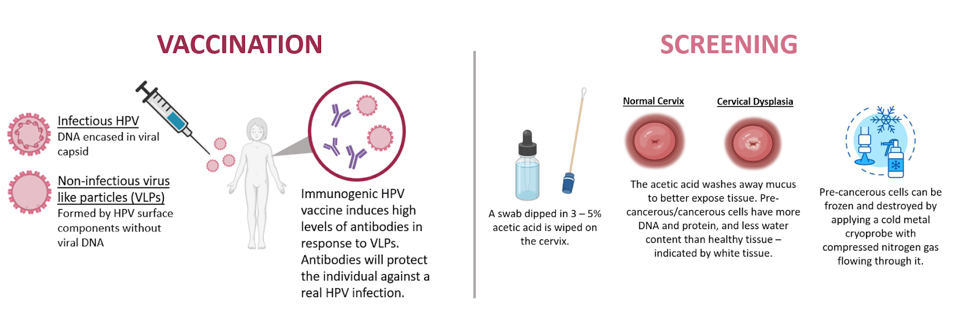

Recognizing this, Likhaan expanded its services through a partnership with Médecins Sans Frontiers (MSF) in 2018 through a campaign to combat cervical cancer by vaccinating over 25,000 young girls against the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is a small double-stranded circular DNA virus that generates seven non-structural proteins and nearly all cervical cancer cases are attributable to persistent infection by HPV. Chronic infection can cause abnormal changes in the cells of the cervix, making them precancerous. Over 100 strains of HPV exist; however, types 16 and 18 cause around 70% of all cases of cervical cancer. HPV types 16 and 18 have long regions known as URRs, upstream regulatory regions, which contain binding sites for E1 and E2 proteins which are important for viral replication. Infection of the basal layer of the epithelium with HPV results in the virus using the host DNA replication machinery to synthesize its viral DNA at a low copy number (Figure 2). Once at the suprabasal layers of the epithelium, the virus changes to a rolling circle mode of DNA replication resulting in high copy number DNA replication and viral assembly. Excessive proliferation of the basal layer cells and a high number of mitosis events, some of which are abnormal, are features of premalignant and malignant disease.

The annual burden of cervical cancer in the Philippines is 7,897 cases and 4,052 deaths. Women in impoverished communities such as those in the Tondo slums are unable to afford health services and are not covered by the government’s cervical cancer prevention initiatives. Women in low- and middle-income countries account for 87% of all deaths from cervical cancer, though only 5% of women in these regions have ever been screened for the disease. The MSF-Likhaan partnership led to 90% of the girls reached receiving both doses of the vaccine and over 1,200 women being screened for indicators of cervical cancer from January to September 2017. In low-resource regions, and countries like the Philippines that need to develop healthcare infrastructure (i.e., diagnostic labs and trained health workers), Pap smears are not a feasible screening option nor are they affordable. Instead, vinegar screening is performed by swabbing the cervix with acetic acid to test for signs of abnormal tissue. If the swabbed region of the cervix turns white within one minute, this indicates precancerous changes in the tissue (Figure 3). In less than three minutes, women are screened for precancerous cells for less than $1 per patient (as compared to $15 per Pap smear of HPV DNA testing) and can be treated at the same visit with cryotherapy or referred to local hospitals for advanced cases.

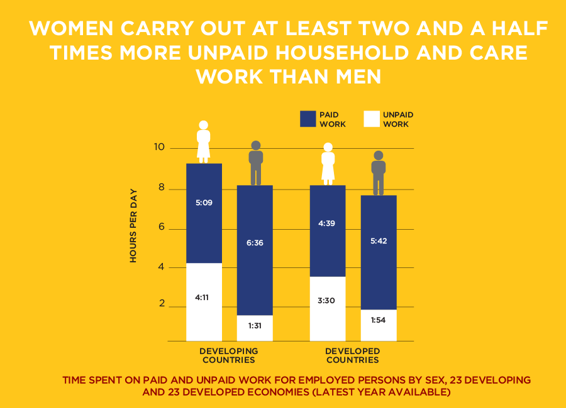

Investment in cervical cancer prevention through vaccinations and screening is just one example of how we can improve women’s health and quality of life, even in regions with limited access to resources like the Philippines. Although the Philippines is working to be a place for the development of women – Likhaan, the necessity to empower and uplift women through expanding and improving women’s health applies across the globe. The Davos 2023 session on the “Economics of Women’s Health” highlighted that more focus needs to be put on women’s mental, menstrual, and cardiovascular health among other health concerns which remain critically underserved. Furthermore, more emphasis must be placed on the diagnostic needs of women as there is currently not enough investment in preventative care. Globally, women carry out at least two and a half times the amount of unpaid household and care work than men (Image 2). Consequently, they often do not take the time to address their own health needs, demonstrating the impact of both the gender pay gap and the gender health gap. Therefore, distribution, pricing, and access to diagnostics and treatments will also be key to ensuring improvements in women’s health. Since women’s health has been synonymous with reproductive health in the past, there has been broad neglect of it as a central issue independently. To date, only 4% of biopharma research and development spending goes toward female-specific conditions. Furthermore, of 37 total prescription drugs approved by the FDA in 2022, only 2 were for female-specific health conditions.

The gender health gap, which describes the ways in which one’s gender identity can have an impact on the medical attention and treatment received, may largely be attributed to the centuries-old perspective that a woman’s ability to bear children defines her unique identity. This has led to medical discourse associating women with the body and men with the mind. Not only has this discourse misrepresented the true fundamental biology, but it has also diminished the autonomy society allows women to have over their own bodies. Biomedicine has, and in many ways continues, to define female and male bodies as distinct but not equal. As much as we would like to believe that science is an objective apolitical space, the reality is that its progress is only possible with society’s blessing. It is therefore its own political institution. Much like the hallowed halls of our capitals; labs, clinics, and all the other spaces from basic research practices “at the bench” to bedside have been predominantly occupied and governed by men. Excluding women from the equation has generated significant disparities at the levels of the treatment of an individual’s body and the treatment of that body in the public.

For decades prior to the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH)’s acknowledgment of the significance of sex as a biological variable (SABV) in 2014, most animal studies were conducted in male mice, rats, pigs, and dogs. Once again, the factor of female reproductive capacity biased biomedicine. Researchers would avoid including female animals in basic science studies out of concern that their reproductive cycles and fluctuations in hormones would confound results designed with stringent controls. Cell and animal models are the beginning of therapeutic development; therefore, excluding consideration for female biology at this fundamental step has severe consequences for healthcare in women. A study conducted in 2010 found that 75% of studies conducted in three highly cited immunology journals did not specify the sex of the animals. Other studies have found that women have more strokes than men and have poorer functional outcomes; however, only 38% of animal studies on strokes included females. A more recent study from 2021 found that of 303 articles surveyed, 352 different cell cultures were used, and across these studies, 96.3% of them did not report the sex of the cells. Of the 11 cell cultures that were reported, sex was not considered as a variable but merely reported. In several cases, certain commercially available cell lines are only derived from male subjects.

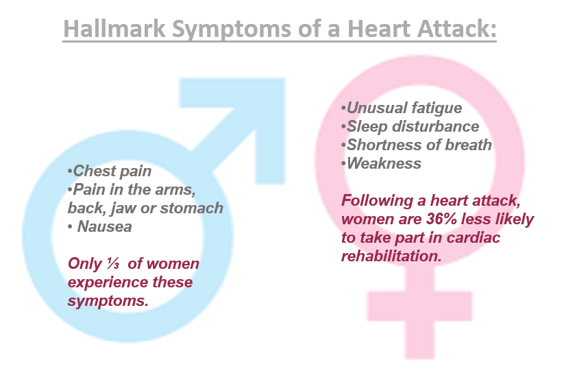

Therefore, a lack of oversight for female health at the bench manifests in more severe issues as we progress through the translational medicine pipeline toward the bedside. Likewise, not considering differences in clinical manifestations of disorders in women (Figure 4) has a significant impact on patient outcomes for women. Women are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions as compared to men; 80% of people who suffer from autoimmune disorders are women, and only one-third of women experience heart attack symptoms common in men. Yet with most research studies being based on results from young white male subjects, women are more likely to experience adverse effects from antihistamines, antibiotics, and other classifications of drugs. Currently, women only make up only 35% of individuals studied in cardiovascular research and most medications have only been tested in men.

As declared at the 2023 World Economic Forum, to improve women’s health, we must empower women to prevent unintended pregnancies, champion universal health coverage, and drive innovation to create leapfrog advances. There is hope for expanding research to advance women’s health and treatment options through innovation. The 2023 Davos session also introduced a new global healthcare company founded in June 2021 as a spin-off from Merck & Co, Organon. There has been little to no previous investment in pharmaceuticals specific to women’s health because the pharmaceutical industry is not typically gender-focused. However, Organon is striving to increase investment in innovation for pharmaceuticals targeting women’s health needs by investing in more than just maternal and reproductive health. Since their 2021 debut, Organon has begun work on treatments for contraception, fertility, and breast cancer, with plans of expanding work on postpartum hemorrhage, preterm labor, endometriosis, cystic ovarian syndrome, bacterial vaginosis and potential work in the areas of anemia, migraines, and cardiovascular health.

Science is its own political establishment influenced by various other political entities. It is one which is also guilty of enforced patriarchal institutions and biases. For centuries, men have kept women out of politics and studies, but also out of research, scientific education, and medical practice. This sex bias has further played out at the intersections of race and class. Keeping women, especially women of color, women of lower socioeconomic status, and women of other underrepresented backgrounds out of legislation, science, and medicine has resulted in major gaps in understanding and respecting female physiology and providing adequate holistic health care. As Dr. Melgar of Likhaan alluded to, expanded funding and improved technology can only go so far as improving women’s health and must be grounded in changing our fundamental belief systems to value women. To give the female body a place at the table, under the microscope, at the bench, and in a white coat at the bedside is to restore, in some part, her bodily autonomy and assert that she is equally deserving of her universal, indivisible, and interdependent human right to health.

Peer Editor: Fanting Kung