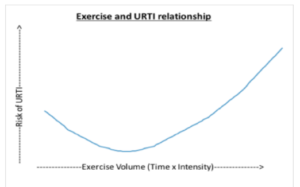

The relationship between exercise intensity (or volume) and susceptibility to upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) is a rotated J-shaped curve. This means that some regular moderate physical activity decreases the relative risk of infection below that of a sedentary individual. However, high intensity exercise or periods of much strenuous exercise can increase risk of infection. Fahlman and Engels showed a 45-50% increase in URTI prevalence in college American football players during high volume training periods. The volume of exercise needed to increase chances of URTI is usually only undertaken by higher level athletes.

How does the immune system function?

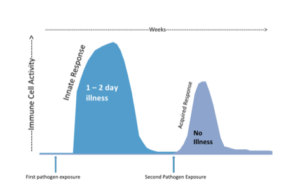

The immune system is responsible for defending organisms against infectious bacteria, viruses and fungi (known as pathogens). The human immune response is made of two components: the innate response and the acquired response. The innate response is the first, non-specific wave of resistance when encountering an infectious substance for the first time. The acquired immune response is the trained response of the immune system. This response develops after the body has come into contact with a pathogen for the first time and subsequently educates thymus immune (T) cells and bone immune (B) cells on the shape of the pathogen. However, after the acquired response has been established, elimination of the pathogen the second time it enters the body can happen in as short a time span as a couple of hours and illness may never manifest.

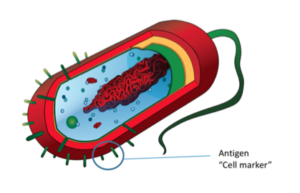

The innate response is partly composed of physical barriers such as our skin and mucous membranes. The primary ways pathogens enter the body are though consumption (food/drink) or inhalation. Inside the digestive tract and respiratory tract are mucous membranes that create an acidic environment hostile to pathogens. Beyond the exterior barriers of defense, the innate immune system also has an army of cells that work together to kill pathogens. These cells work by engulfing pathogens and by communicating to other immune cells to increase activity. Lastly, the innate immune response educates T cells and B cells on the pathogen’s signature marker (antigen) so that the next time this pathogen contacts the body, the acquired immune response kicks in quickly.

The specificity and quickness of the acquired immune response is the most critical difference between the acquired and innate responses. The primary job of the acquired immune response is to prevent pathogens from colonizing, to keep pathogens out of the body, and to seek and destroy certain invading pathogens. Much of what makes the acquired response so powerful are the T & B lymphocyte cells. After encountering a pathogen for the first time, the T & B lymphocyte cells are “educated” on the proper response to the pathogen. After a second encounter, the T & B cells quickly duplicate cells targeted at the specific pathogen. About 90% of these lymphocytes go to attack the pathogen and communicate to other immune cells to attack while 10% stay back for future attacks. The “memory” of the acquired response lasts for years.

We know now how the immune system generally works, but how does the immune system respond to exercise?

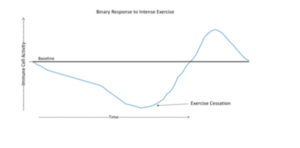

During moderate exercise, the innate response will enhance immune cell function. Conversely, during high intensity exercise, the innate response will decrease immune cell function. Moderate intensity exercise evokes moderate levels of catecholamines (stress hormones) which may increase immune cell levels, while high intensity exercise evokes high levels of catecholamines which may decrease immune cell levels. However, 2-3 hours after intense exercise, some immune cells are at their highest levels, which might lead to a more productive immune system as long as the exercise session did not exceed an hour.

As for the acquired immune response, it changes in proportion to the intensity and duration of the exercise session. T cell function can increase after exercise if the session is not too long or too intense. During long and/or intense exercise sessions, the mobility of T cells is reduced, giving pathogens a longer time to colonize before they are attacked by T cells.

The most important finding in exercise immunology is that beneficial immunological changes take place in response to moderate exercise. With each moderate session of exercise, a boost in immune system activity could reduce risk of infection. On the other end of the spectrum, trained/elite endurance athletes seemed to be more at risk to developing an infection 3 to 72 hours following a very intense session of training. This 3 to 72 hour timeframe following intense training has been called the “open-window” theory and may be more applicable to individual elite level sporting events. When exercise sessions increase in time or intensity, aspects of an athlete’s innate and acquired immune system function will be depressed but not completely inactive. What this means is that athletes engaging in hard periods of training are at increased risk of picking up the common cold or flu, but not at more risk of catching a serious illness.

As with nearly everything in physiology, the dose of stress or stimulus dictates the response. This seems to be the case with exercise and immune function. A moderate amount of activity seems to be beneficial in boosting immune function, but going overboard with exercise may put you at an increased risk for infection. However, this is mostly a concern for elite endurance athletes. Most people would reap the benefits of increased immune function associated with increased exercise!

Peer edited by Michelle Engle and Mimi Huang.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: