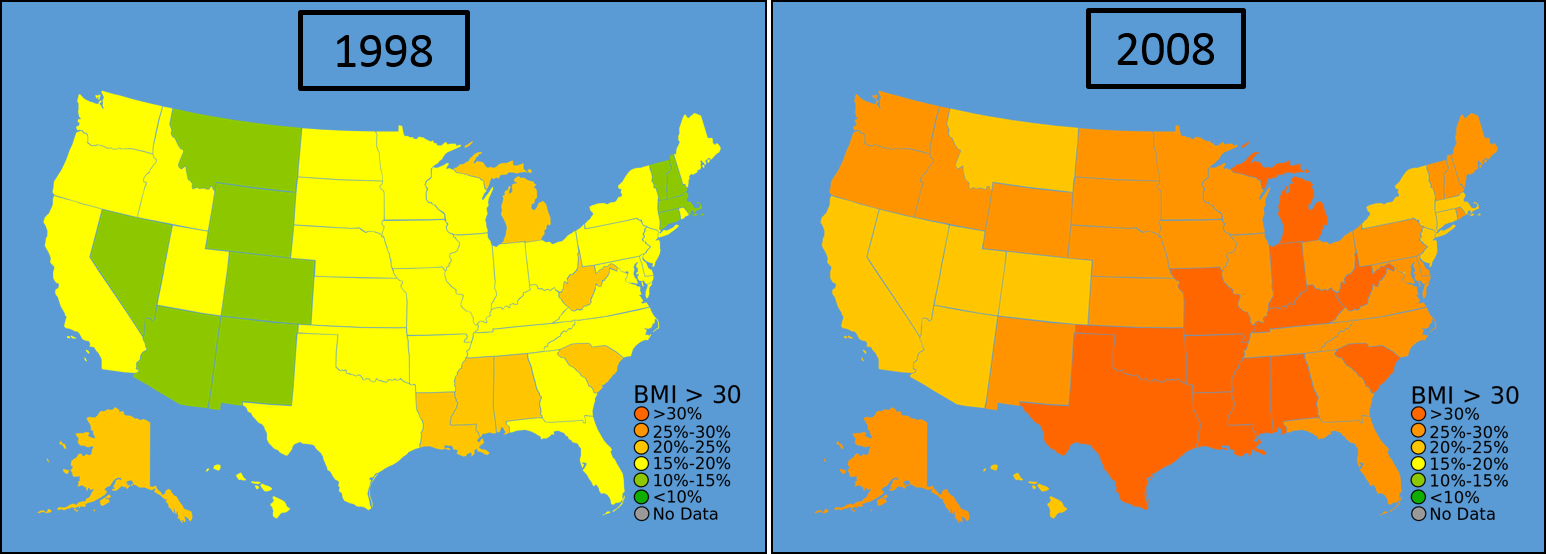

Over a third of the adult population in America is obese (Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 30) and an additional 40% are classified as overweight (BMI 25-30). Within the past ten years, this rate has increased significantly. Obesity increases risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers. According to some estimates, the medical costs of an obese person is $1429 more than a person of normal weight. While exercise and diet are very important factors that regulate a person’s weight/obesity, there may be something else interfering with the body’s natural weight regulating processes: obesogens.

Coined in 2006, the term “obesogens” refer to chemicals that may predispose an individual to gaining weight. Scientists have observed that numerous chemicals caused weight gain and obesity in animal studies, including tributyltin (pesticide), BPA (in plastics), phthalates (in plastics), PBDEs (flame retardants), and fructose (in diet). Persistent exposures to these chemicals in adult and particularly in early life, even in small doses, can have lifelong implications.

Since the field of obesogens is relatively new, how these chemicals affect obesity is still being discovered. Some chemicals act by reprogramming stem cells to differentiate into fat cells, thus increasing the number of fat cells in an individual. This number contributes to determination of the metabolic set point of an individual, or the set weight that the body is programmed to maintain. Fat cells also secrete hormonal signals that affect metabolic regulation throughout the body, such as leptin. These hormonal signals also influence neurological signals in the brain that control feeding and satiety. In addition to increasing the number of fat cells, obesogens may also target metabolism and the brain directly.

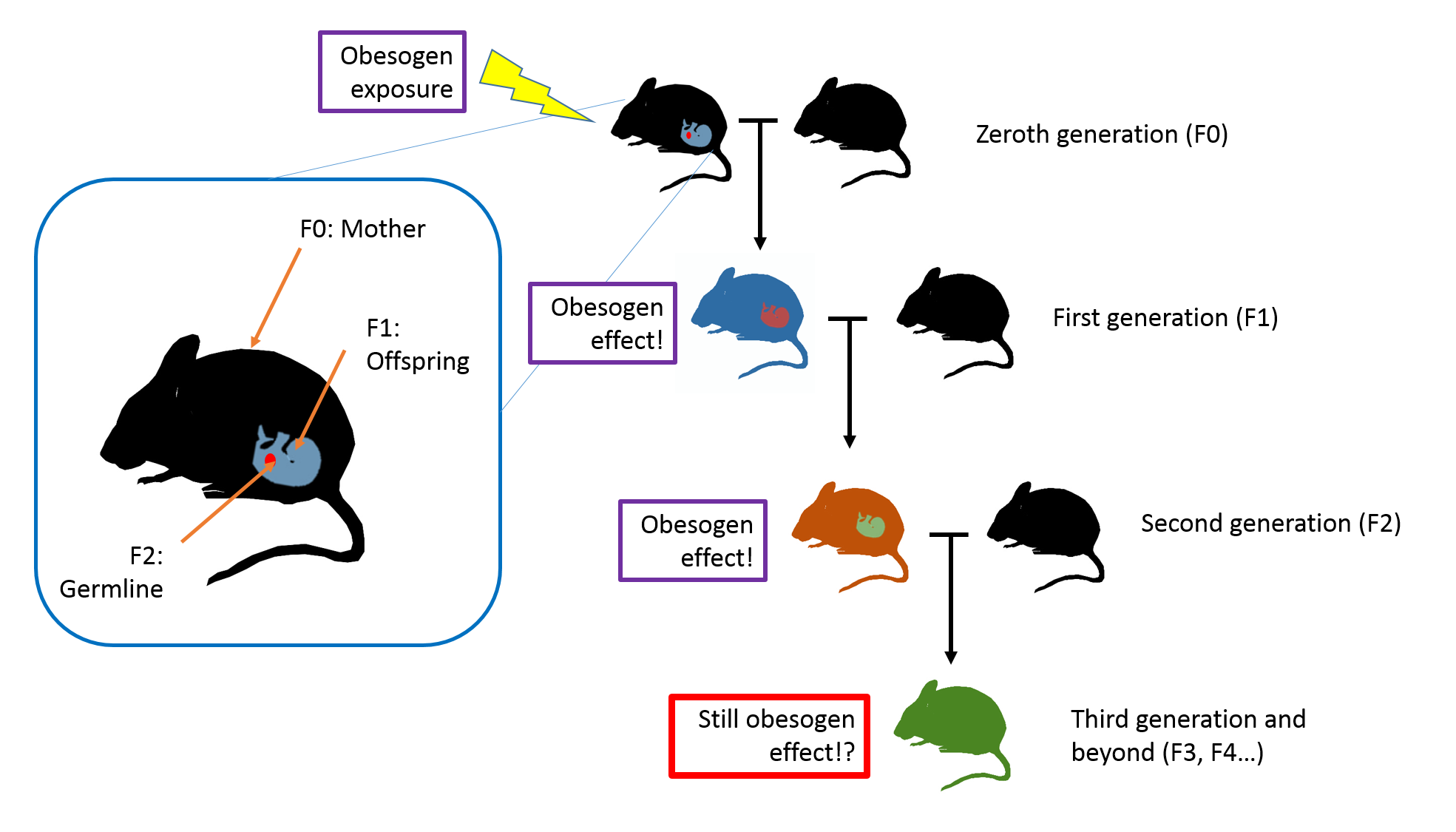

Some obesogens have transgenerational effects, where an effect of an exposure is seen in a generation that has had no direct exposure to the chemical. Researchers are finding that when animals are exposed to these chemicals, effects can be seen in their offspring and even the third generation! In other words, the effects of exposure to these obesogens may be heritable. These fattening signals could be passed on through genes or through epigenetic markers.

Obesity is a growing public health problem with serious health consequences. Increasing scientific evidence supports the idea that obesogens may be predisposing people to becoming obese. The transgenerational effects of obesogens highlights the importance and urgency of this kind of research, in order to protect not only the pregnant mother and her child, but also the third generation and beyond. Continued research in this field, mostly funded through the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, will support the establishment of policies that would regulate production and exposure to these chemicals. In the meantime, while obesogens might play their part, we also need to play ours. We should strive to maintain healthy lifestyles and eating habits, which are well-known methods to improve health.

Peer edited by Joanna Warren

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: