With my precious free hours away from working towards my PhD, I spend a large percentage of them training as a powerlifter. This looks like a few hours at the gym a few times a week, during which I am mostly squatting, benching, and deadlifting (meaning yes, this is a different sport than the weightlifting you might have just watched during the Olympics).

When you think “powerlifter,” maybe you picture a massive dude in a stringer throwing weights and chains around. As a lightweight, female-identifying lifter, I will be the first to challenge that view and direct your attention to many other incredibly strong women in powerlifting.

Another common stereotype is that powerlifters choose this sport because it doesn’t require speed, cardiovascular endurance, or strict dieting like other strength sports. In other words, powerlifters are powerlifters because they can sit around between exercise sets eating candy (ahem…rapidly-absorbed intra-workout carbohydrates), and skip the treadmill. Admittedly, this assumption derives from pretty common practices; even I keep a stash of sour watermelons in my gym bag. I mean come on, who doesn’t want to snack on gummies during a workout?

On the flip side, however, it is also common to hear elite athletes, coaches, and exercise scientists encourage healthy diet practices and non-sedentary lifestyles to help maximize results in the gym. For instance, tracking macronutrients to consume certain proportions of protein, carbohydrates, and fat can both fuel your body for a workout and help your muscle synthesis and recovery afterward. Other experts also recommend General Physical Preparedness training, which can range from conditioning sessions to hiking to abdominal core work, in addition to specific sports training to help increase general cardiovascular and non-specific strength and endurance.

As much as I might want to indulge my lazier impulses and fall into the candy-snacking, treadmill-avoiding category, I do mostly take the expert advice and make efforts to monitor my diet and stay active. However, I am not so committed that I’m taking up extra training activities (I do have a PhD to finish); instead, I have a daily step goal.

Do steps a day keep the doctor away?

Whether you consider yourself an athlete or not, it is likely you’ve at least heard of a daily step count, and maybe even have your own personal goal. Intuitively, we can assume walking is better for our health than sitting on the couch, but does science back this up? Is hitting a step goal enough to confer benefits (besides the satisfaction of your watch buzzing, or closing your rings)? A recent systematic review provides a simple, yet striking answer: yes!

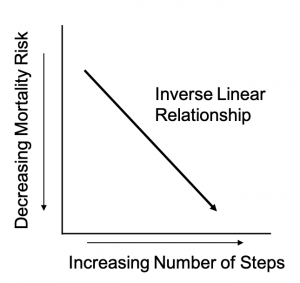

In this review, the authors performed a meta-analysis of multiple studies on step counts and all-cause mortality. For participants grouped at 1000-step intervals, they computed a hazard ratio, or a measure indicating whether participants in a given daily-step group decreased their risk of mortality compared to a control group of participants not taking that number of steps. They found an inverse linear relationship and dose-response where more daily steps correlate with a lower risk of all-cause mortality. Further, the relationship between steps and decreased mortality risk persisted when other demographic and health factors, including body mass index and smoking status, were taken into account.

Essentially, an increased number of steps decreased the risk of mortality of ANY cause, regardless of existing health status. Athlete or not, that is some serious motivation to lace up your walking shoes.

Despite the clear health benefits, for the average person busy with work, family, and life, it may not be realistic to suddenly add in 8,000 more steps every day. Encouragingly, your step goal doesn’t have to be the notorious 10,000 steps – that specific number has not been supported as the “optimal” goal. Further, small increases in activity still make meaningful improvements on your health; as the review concluded, each incremental increase in step count corresponds with an incremental decrease in risk of all-cause mortality. Simply adding in a walk around the block after dinner or taking breaks from a sedentary office job to walk around can make a difference.

Plainly, this review (and those studies included in the meta-analysis) show that taking more steps is better for you. Importantly, this benefit occurs regardless of one’s current health status; walking more is good for anyone, no matter your starting point. I’m personally encouraged by this evidence supporting my morning walk’s benefit on my physical health and might even increase my daily goal…if not just to counter my gummy habit at the gym.

If you are looking to take steps to improve your health, I recommend starting with literal steps.

Peer Editors: Deanna Corin & Devan Shell