Bacteria are a big part of who we are as humans. They live all over us, forming distinct communities, or microbiomes, on our skin, in our hair, in our mouths, and in our guts. We host these microbes, and increasingly we’re learning that in turn they have a profound effect on our health. This is particularly true when it comes to the gut microbiome, which has been linked to conditions like Crohn’s disease and Irritable Bowel Disease.

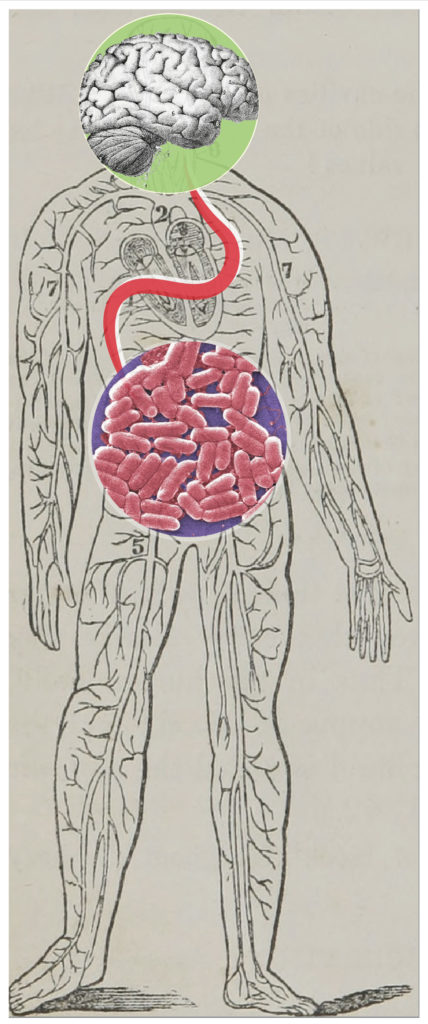

The idea that the bacteria making a home in our guts have a role in our intestinal health doesn’t seem that far-fetched, but for several years there have been intriguing suggestions that our gut bacteria may also have an influence on our mental health.

This has lead to a lot of hype around the idea that our gut bacteria may be controlling our moods or appetites to further their own ends. Experiments in mice and small-scale human studies have shown correlations between mood disorders like anxiety and depression, and alterations in gut microbiome composition.

It’s long been known that there is an intimate connection between the gut and the brain. Often termed the gut-brain-axis, this connection is like an eight lane highway facilitating a constant exchange of chemical information between the central nervous system and your belly. Ever since it was discovered in the 1980’s that bacteria produce compounds that have significant similarity to human hormones like insulin, scientists have wondered if gut bacteria may influence our mental state by producing their own sets of chemical signals.

But the field hasn’t quite gotten far enough to definitively say how exactly that process might be taking place. This problem is particularly challenging because of how hard it is to make observations in the human gut. How can we work out what gut bacteria are doing if we can’t directly see them?

Now, recent work from a group in Belgium has made one of the first efforts to address this question and functionally characterize how bacteria might influence mental state.

By comparing the gut microbial compositions and quality of life scores among a cohort of 1,054 Belgians, the group was able to test if particular bacteria were correlated with different mental health markers. While this type of association study isn’t new, what is most exciting about their work is that they have developed a method for characterizing the neuroactive potential of certain gut bacteria.

The group built what they call “gut-brain modules,” which are essentially groups of genes associated with the synthesis of compounds with potential to interact with the human nervous system. They constructed 56 such modules, all centered around a different neuroactive molecule, such as dopamine or serotonin.

By applying this gut-brain module framework to the gut microbial makeups of patients diagnosed with depression, they were able to identify and verify a single gut-brain module correlated with higher scores for social functioning. This module is associated with metabolism of Dopamine, a neurotransmitter that has been linked to pleasure and depressive disorders.

While this study doesn’t go so far as to argue a causative role for gut microbes in mental health, it does demonstrate a feasible approach to studying the black box of the human gut and that we may be one step closer to understanding the role microbiomes play in our health.

Peer edited by Gabrielle Dardis.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: