Do you remember when Wilmington, NC made national news in 2017 for having serious chemical contamination in their drinking water? An investigation by the EPA had identified that a chemical-manufacturing plant Chemours (a spin-off of DuPont, one of the largest chemical-manufacturing companies in the world) had been dumping the chemical known as GenX into the Cape Fear River, which is a drinking water source for residents of Wilmington. The issue was that, at that time, there was only limited information on GenX, a relatively new man-made chemical. Despite the limited information, the State ordered Chemours to stop their dumping. Perhaps a previous lawsuit against DuPont regarding C8 helped facilitate the State’s decision? Even so, there is still an ongoing effort to investigate and prevent GenX contamination in the area. The good news is that on February 14, 2019, the EPA announced a nationwide action plan for PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), in which GenX is included.

PFAS are a group of man-made chemicals, manufactured and used widely since the 1940s. They are often used in food packaging to make things grease and stain resistant (Teflon is also a type of PFAS!) but are also found in firefighting foams and have industrial applications. The drinking water contamination reported in Wilmington is an example of high-level exposures to such PFAS, and similarly, there could be other communities that are exposed to drinking water contamination from industrial facilities or places that use firefighting foams. Elevated PFAS exposure is concerning since these substances accumulate in our bodies, and an increasing number of studies link high-level exposures to adverse health outcomes.

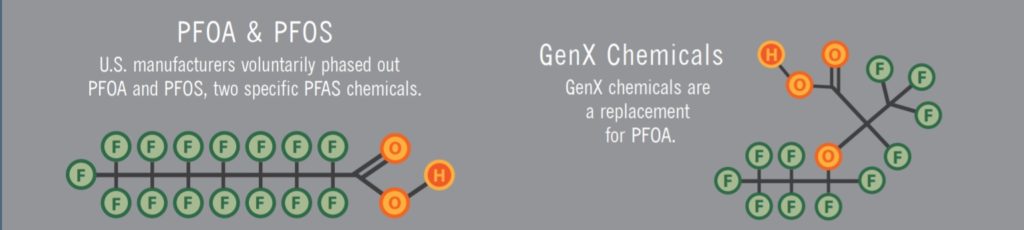

Source: EPA PFAS infographics

Amongst PFAS, the two of the most commonly used chemicals were PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) and PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid).

An increasing number of studies observed PFOA and PFOS accumulate in the human body and linked them to adverse health outcomes related to infant birth weights, immune system, cancer, and thyroid function. Due to the increasing health concerns, US manufacturers voluntarily phased out the two PFAS chemicals between 2000 and 2002, replacing them with new PFAS such as GenX. However, there is limited information about the potential adverse health effects in humans for the emerging PFAS, and we can still be exposed to PFOA and PFOS on multiple occasions. You could be unknowingly exposed to high levels of emerging PFAS, as in the case of drinking water contamination in Wilmington. Maybe you still use some consumer products that were manufactured before the phase-out of PFOA and PFOS. Even if you managed to get rid of all those products at home, PFOA and PFOS may be present in our surrounding environment since they do not break down easily. Or, consumer products manufactured internationally may contain PFOA and PFOS, if these substances are not regulated as in the US. So you can see here how difficult it would be for an individual to avoid high levels of exposures to chemicals that are known to be harmful to human health, and a combined effort at a population level is needed, like the PFAS action plan released by the EPA.

(Bloomberg Environment)

The PFAS action plan consists of regulatory actions to restrict on the known “bad actor” compounds, along with short- and long-term plans to better understand the exposure levels and potential health outcomes associated with PFAS, including the emerging compounds. Since PFOS and PFOA are the most commonly used types of PFAS with evidence of harmful human health effects, they are a high priority in administering regulations. Currently, PFAS are not regulated and there is only a non-enforceable and non-regulatory advisory level called “health advisory level”. The health advisory level, established in 2016 for PFAS, state that if both PFOA and PFOS are found in drinking water, the combined concentrations of PFOA and PFOS at 70 parts per trillion is the margin of protection for all Americans throughout their life. To enforce mandatory and nationwide regulations, the EPA is planning to include PFOA and PFOS in multiple laws and regulations.

There is no doubt that the comprehensive action plan for PFAS laid out by the EPA will help communities that are already affected by PFAS contamination, and advance the current state of knowledge. However, there is one more issue that requires careful attention – a concept called “regrettable substitution”. Under the current system, implementing regulations on a substance with known adverse human health effect could unintentionally bring about the same problem again with a substituting substance: manufacturers often replace a substance under regulation with a substituting substance that has similar chemical properties as the substance under regulation but has not been identified as a “bad actor”. Commonly, there is just not enough evidence on the substituting substance for it to be labeled as a “bad actor”: the chemical could be completely new to the market or just been used rarely that it was not sufficient to trigger noticeable adverse health outcome in humans. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence! A classic example is the phase-out of bisphenol A (BPA) and replacement with bisphenol S (BPS). Mounting evidence in potential health outcomes associated with BPA led to voluntary phase-out of BPA by manufacturers and replacement with various substitutes including BPS. However, the toxicity and potential human health effects of these substituting chemicals were unknown at the time of substitution. Shortly after BPS became widely used as the substituting chemical for BPA, studies observed that the substituting chemical BPS was as harmful as the substituted chemical BPA. The replacement of BPA with BPS is not the only example of such regrettable substitution; man-made chemicals such as diacetyl, organophosphate pesticides, and polybrominated flame retardants are also well-known examples. The case of PFOA substitution with GenX could also be viewed in this perspective. There is increasing animal studies that identified potential harmful effects of GenX, but limited studies on human health. Upon future studies, GenX could also end up being a regrettable substitution! Given the repeated history of regrettable substitution in the man-made chemicals, it is now a time to take a step back and revisit the effectiveness of the current framework and develop a more stable platform to aid the selection of safe alternatives.

Want to learn more about how different countries are trying to tackle regrettable substitution? Visit the EPA website and the European Chemicals Agency website

Want to learn more about PFAS and EPA’s action plan? Visit EPA website that includes information on the PFAS action plan, data, and state-specific resources!

Want to learn more about drinking water contamination by PFAS in the US? Visit a website with an interactive map, developed by SSEHRI, Northeastern University.

Peer edited by Brittany Shephard and Candice Crilly.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: