The taxi driver went quiet, as if lost in thought. I waited, kept patient by that mysterious gut feeling that someone is about to say something.

“Tell me, why haven’t we cured cancer yet?”

Conversations about what I do often lead to this question – in taxis, on buses, even once in a nightclub. It’s a question that led me to pursue a career as a cancer biologist. People ask because, despite all the news articles about promising treatments and breakthroughs, cancer is still common. Over half a million people are predicted to die from cancer in the US in 2016.

A cure for cancer may not be impossible but it is elusive, for a few reasons.

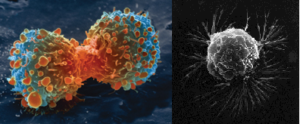

Cancer arises from cells with DNA that is damaged in such a way that allows the cells to divide rapidly and uncontrollably. These cells form a tumor that can spread around the body, causing harm to organs and normal bodily processes.

However, there is no single recipe for cancer. Scientists have shown that damage to any one of 93 places in the DNA of a single healthy breast cell can turn it into a cancer cell. Even within a single tumor, each cell could be damaged in different ways. Many current medicines treat different but specific sorts of damage that not all cancer cells have, so they cannot treat all cancers.

Another problem is that the cancer is, well, you. When we search for new antibiotics for bacterial infections, one advantage we have is that bacteria and human cells have some differences. This allows us to look for medicines that kill bacteria, but not human cells. Cancer cells, on the other hand, are our own cells, only damaged. This makes the task of finding a medicine that can distinguish between a cancer cell and a healthy cell incredibly difficult.

To make things worse, cancer cells are constantly changing and can adapt to tolerate medicines, meaning they often survive treatment. When this happens, the cancer becomes “resistant” and we need to switch to another medicine, if there is one.

So it is unlikely we will be able to cure all cancers with one medicine in the near future. But there’s some good news.

We can already treat some types of cancer, particularly if they are caught in the early stages and are still vulnerable to the medicines we have. As many as 9 out of 10 people diagnosed early with Hodgkin’s lymphoma – a type of blood cancer – are still alive 5 years after diagnosis, and many patients make a full recovery. The more we find out about the different types of cancer, the more medicines we can make. Having a greater array of medicines will allow us to personalize treatment plans to the type of cancer a patient has.

That’s not to say that scientists have given up on our one cure for many cancers, though: we’ve just got to try a different approach. The current big idea is to get our own immune system to kill the cancer cells.

Most of the time, our bodies are pretty good at seeking out damaged cells and destroying them, but cancer cells survive because they have learned to escape. Medicines are being developed – called “immunotherapies” – that help the immune system find these cancer cells and kill them. We’ve got to fine tune them as they currently have nasty side effects, but they may work for a wider range of cancers compared to current medicines.

With any luck, we will increase our arsenal with a mix of more medicines that treat specific cancers and broader medicines like immunotherapies. We may never cure cancer completely, but we can keep trying new approaches in the hope we will drastically improve survival.

The taxi driver put it well:

“So cancer is a wily beast we’ve just got to keep taming.”

As a research scientist, I’m cautiously optimistic.

Edited by Mimi Huang