With each flu season comes a bombardment of new advertisements reminding people to get a flu vaccine. The vaccine is free to most and widely available, yet almost half of the United States chooses to forgo the vaccine.

When Ebola emerged, there was 24 hour news coverage and widespread panic, but the influenza virus (the flu) feels more familiar and much less fear inducing. This familiarity with the flu makes its threat easy to brush aside. Yet, every flu season is met with stern resolve from the medical community. What’s the big deal with the flu?

What makes the flu such a threat?

Influenza is a globetrotting virus: flu season in the northern hemisphere occurs from October to March and April to September in the southern hemisphere. This seasonality makes the flu a year round battle. The virus also evolves at a blistering pace, making it difficult to handle.

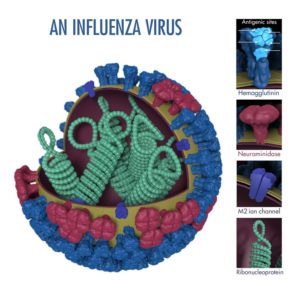

To understand why the flu is able to evolve so rapidly, its structure must be understood.The graphic to the right shows an illustration of the ball-shaped flu virus.

On the outside of the ball are molecules that let the virus slip into a person’s cells. These molecules are called hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, simply referred to as HA and NA. HA and NA are also used by our body’s immune system to identify and attack the virus, similar to how a license plate identifies a car.

These HA and NA molecules on the surface can chanAntigenic shift in the fluge through two processes. One such process is like changing one license plate number; this is known as antigenic drift. When the flu makes more of itself inside a person’s cells, the instructions for making the HA and NA molecules slightly change over time due to random mutations. When the instructions change, the way the molecules are constructed also changes. This allows the flu to sneak past our immune systems more easily by mixing up its license plate over time.

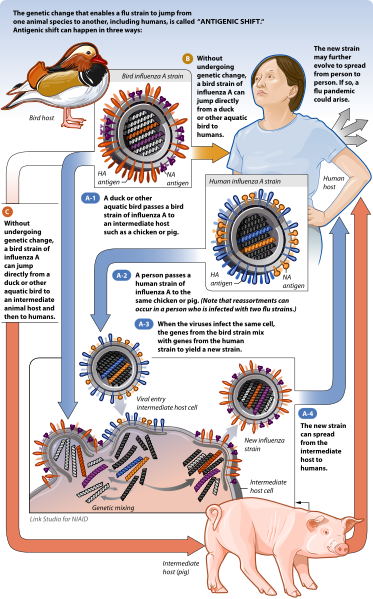

Another way the virus can evolve is known as antigenic shift. This type of evolution would be more like the virus license plate changing the state it’s from in addition to a majority of its numbers and letters, making the virus completely unidentifiable to our immune systems. Unlike antigenic drift, antigenic shift requires a few improbable factors to coalesce.

Antigenic shift happens more regularly in the flu when compared to other viruses.For instance, one type of flu virus is able to jump from birds, to pigs, and then to people without the need for substantial change. This ability to jump between different animals enables antigenic shift to occur.

This cross species jumping raises the odds of two types of the virus to infect the same animal and then infect the same cell. When both types of the flu virus are in that cell, they mix-and-match parts, as can be seen in the picture to the right. When the new mixed-up flu virus bursts out of the cell, it has completely scrambled it’s HA and NA molecules,generating a new strain of flu.

Antigenic shift is rare, but in the case of the swine flu outbreak in 2009, this mixing-and-matching occured within a pig and gave rise to a new flu virus strain.

This rapid evolution enables many different types of the flu to be circulating at the same time and that they are all constantly changing. This persistent evolution results in the previous year’s flu vaccine losing efficacy against the current viruses in circulation. This is why new flu vaccines are needed yearly. Sometimes the flu changes and becomes particularly tough to prevent as was the case with swine flu. At its peak, the swine flu was classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a class 6 pandemic, which refers to how far it had spread rather than its severity. Swine flu was able to easily infect people, fortunately it was not deadly. The constant concern of what the next flu mutation may hold keeps public health officials vigilant.

Why is there a flu season?

A paper by Eric Lofgren and colleagues from Tufts University grapples with the question “Why does a flu season happen?”. The authors highlight several prevailing theories that are believed to contribute to the ebb and flow of the flu.

One contributing factor to the existence of flu seasons is our reliance on air travel. When flu season in the Australia is coming to an end in September, an infected person can fly to Canada and infect several people there, kickstarting the flu season in Canada. This raises the question: why is flu season tied with winter?

The authors touch on this question. During the winter months, people tend to gather in close proximity allowing the flu access to many potential targets and limiting the distance the virus need to cover before infect another person. This gathering in confined areas likely contributes to the spread of flu during the winter, but another theory proposed in this paper is less obvious and centers around the impact of indoor heating.

Heating and recirculating dry air in homes and workplaces creates an ideal environment for viruses. The air is circulated throughout a building without removing the virus particles from the air, improving the chances of the virus infecting someone. The flu virus is so miniscule that air filters are unable to effectively remove it from the air. The authors come to the conclusion that the seasonality of the flu is dependent on many factors and no single cause explains the complete picture.

What are people doing to fight the flu?

The flu is a global fight, fortunately the WHO tracks the active versions of the flu across the world. This monitoring system relies on coordination from physicians worldwide. When a patient with the flu visits a health clinic, a medical provider, performs a panel of tests to detect the type and subtype of flu present. This data is then submitted to the WHO flu database, which is publicly accessible.

This worldwide collaboration and data is invaluable to the WHO; it allows for flu tracking and informed decision making when formulating a vaccine. Factor in the rapidly evolving nature of the flu and making an effective vaccine seems like a monumental task. Yet, because of this worldwide collaboration twice a year, the WHO is able to issue changes to the formulation of the vaccine as an effort to best defend people from the flu that year.

Peer edited by Rachel Cherney and Blaide Woodburn.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: