The average American consumes approximately 58 pounds of beef per year, based on current estimates from the USDA. That’s about four quarter-pounders per week, which is a major problem from the standpoint of combating climate change. The meat industry is a significant contributor to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. By some estimates around 15%. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has recommended that moving towards more plant-based diets is one of the most immediate ways we can reduce global emissions and reach mid-century target CO2 reduction goals.

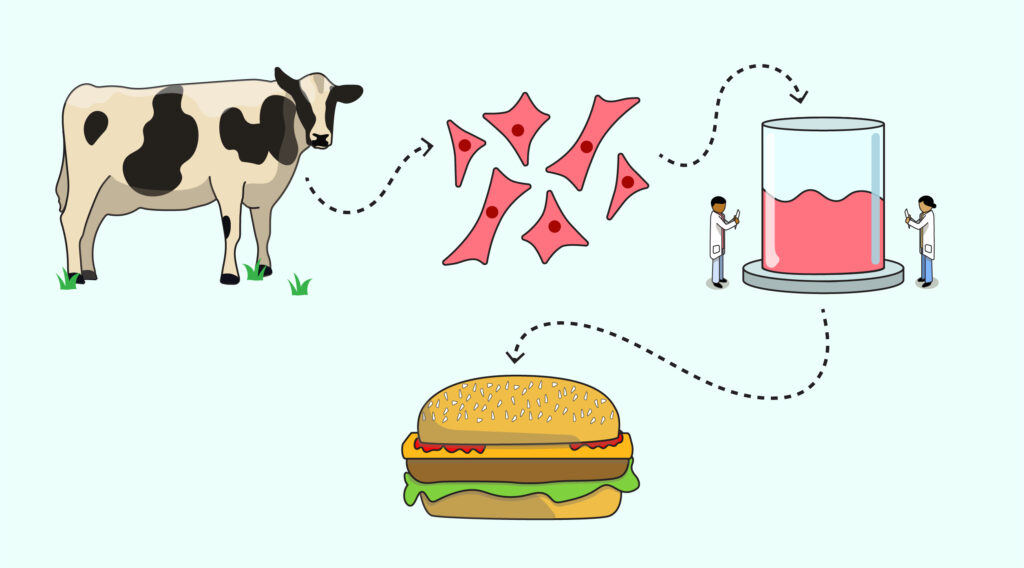

But there are those thinking beyond simply how to get people to eat less meat. Instead they’re turning to cell culture, growing animal cells outside of an actual living animal, to fundamentally reinvent how meat is cultivated.

Cultured meat, also sometimes called in vitro meat, is the process of growing cow, chicken, or fish muscle cells in a dish or vat. Thereafter, a product is created essentially identical to ground meat you’d get from actual animal tissue. The long term vision of cultured meat is easy to see: no need for pastures, no wasted cropland for feed, no manure, and no animal rights issues. The positive impact on reducing carbon and other emissions could be significant, with some studies suggesting that cultured meat may produce as much as 96% fewer emissions than conventional methods. Importantly, cultured meats may also help meet the nutritional demands of a global population expected to hit ~11 billion by the end of the century.

That at least is the dream. The reality is more complicated and involves a more open-ended question. Will these new meat products be able to effectively compete with animal grown meats and the generations old conventional industry that produce them?

A pair of new reports commissioned by the non-profit Good Food Institute (GFI), and another recent study from UC Davis, illustrate for the first time a comprehensive picture of what it will take for cultured meat to achieve these lofty goals. Although the outlook is promising, the report does highlight some of the significant hurdles the industry will have to clear to fulfill cultured meat’s potential.

Perhaps the biggest issue facing cultured meat is the cost. Growing cow cells into a burger is exorbitantly expensive. Famously, the first cultured meat burger cost a mind-blowing $330,000 to make (the reviews of which were less than positive). That was back in 2013, and costs have dropped some as methodologies have improved. More recently Aleph Farms, a cultured meat startup out of Israel, grew a very small steak for $50. Current estimates from the GFI study puts the cost of cultured meat somewhere in the range of $68-$10,000 per pound, depending on the manufacturing process. This is still several orders of magnitude more expensive than the cost of conventional meat which is around $1.10 per pound. Though a direct comparison like this may not be appropriate since the meat industry and agriculture in general are often heavily subsidized by governments. Still, the current cost of producing cultured meat would almost certainly make it prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest consumer.

Why so expensive? The reason largely has to do with the media that’s used to grow cultured cells. Media, in this case, refers to the liquid the cells are growing in. It’s the particular cocktail of proteins and hormones necessary to stimulate cell growth and proliferation. This cocktail can either be found naturally in the blood serum of animals such as Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) or made from individual components produced using recombinant organisms like yeast and bacteria. In either case, it’s a pricey thing to produce, with the various proteins and growth factors needed costing hundreds to thousands of dollars per gram.

The GFI report predicts that with increased capacity and improved methodologies for the production of growth media components, it may be possible to drop the cost of media by 1000-fold. Further cost saving and production efficiency, could stem from increasing the density of cells that can be grown at once. As a result, it may be feasible to drop the per-pounds cost of cultured meat to around $2.5 by 2030. That’s a major improvement, but still 10-fold more pricey than conventional meat, which highlights just how difficult it will be for this new industry to compete with such an established and heavily subsidized industry.

The real selling point of cultured meat isn’t about cost. It is, in theory, about helping save the planet from a climate catastrophe, but how much better is cultured meat compared to conventional in terms of carbon emissions?

The answer is that it depends. Some studies have suggested that the environmental impact of cultured meat will be massively less than conventional, but other more recent reports have highlighted that this greatly depends on how culturing operations are powered. Right now, cultured meat is expected to require quite a bit of energy to power and cool the bioreactors necessary to grow meat at scale. The GFI study reports that with current methods this may mean the carbon footprint of cultured meat is only about as good as conventional poultry and pork production. That’s still a big improvement on the current estimated footprint from beef cultivation, but falls short of the rosy forecast sometimes painted by those in the cultured meat industry.

The good news is that unlike conventional meat production, there’s a lot of room for cultured meat to reduce its carbon footprint. About 70% of cultured meat’s projected carbon emissions can be attributed to electricity use. By building large scale production facilities that use renewable energy, this negative may be largely avoided. Sustainably manufactured cultured meat is expected to be a major improvement, producing a much smaller share of carbon emissions than all other conventionally produced meats.

Addressing the negative impacts that agriculture and land use have on global warming will be a key component of mitigating the worst effects of climate change. While the industry is still in its infancy, the potential for cultured meat to play a significant role in solving these problems shouldn’t be dismissed. There’s still a lot the industry will need to work out to achieve its goals. Nonetheless, burgers, steaks, and chicken nuggets that were grown not in an animal, but in an energy sustainable factory, may very well show up on your plate in the near future with proper investment and innovation.

Peer edited by Chip Norwood and McKenzie Murvin