You’ve heard of MRSA. You may even have heard of XDR-TB and CRE. The rise of antibiotic-resistant infections in our communities has been both swift and alarming. But how did these once easily treated infections become the scourges of the healthcare world, and what can we do to stop them?

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria pose an alarming threat to global public health and result in higher mortality, increased medical costs, and longer hospital stays. Disease surveillance shows that infections which were once easily cured, including tuberculosis, pneumonia, gonorrhea, and blood poisoning, are becoming harder and harder to treat. According to the CDC, we are entering the “post-antibiotic era”, where bacterial infections could once again mean a death sentence because no treatment is available. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, kills more Americans every year than emphysema, HIV/AIDS, Parkinson’s disease, and homicide combined. The most serious antibiotic-resistant infections arise in healthcare settings and put particularly vulnerable populations, such as immunosuppressed and elderly patients, at risk. Of the 99,000 Americans per year who die from hospital-acquired infections, the vast majority die due to antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

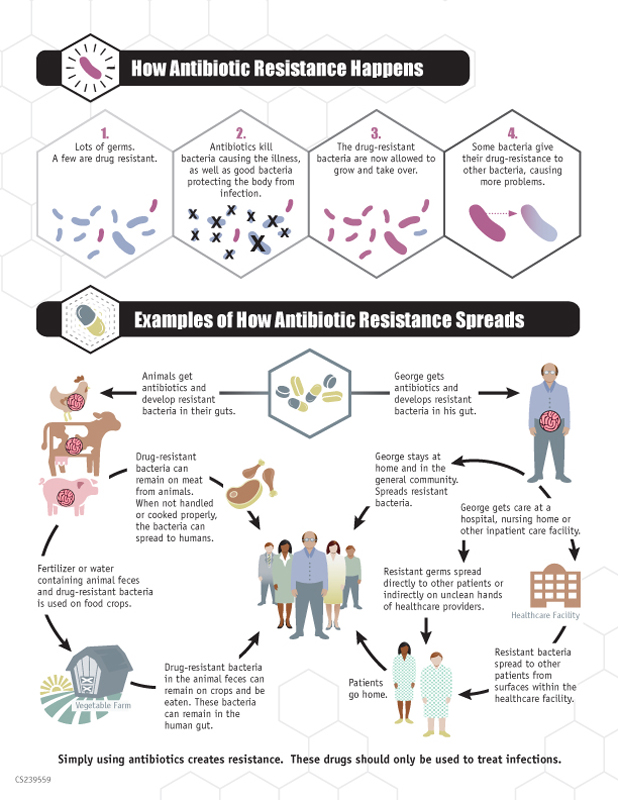

Bacteria become resistant to antibiotics through their inherent biology. Using natural selection and genetic adaptation, they can acquire select genetic mutations that make the bacteria less susceptible to antimicrobial intervention. An example of this could be a bacterium acquiring a mutation that up-regulates the expression of a membrane efflux pump, which is a transport protein that removes toxic substances from the cell. If the gene encoding the transporter is up-regulated or a repressor gene is down-regulated, the pump would then be overexpressed, allowing the bacteria to pump the antibiotic back out of the cell before it can kill the organism. Bacteria can also alter the active sites of antibacterial targets, decreasing the rate with which these drugs can effectively kill the bacteria and requiring higher and higher doses for efficacy. Much of the research on antibiotic resistance is dedicated to better understanding these mutations and developing new and better therapies that can overcome existing resistance mechanisms.

While bacteria naturally acquire mutations in their genome that allow them to evolve and survive, the rapid rise of antibiotic resistance in the last few decades has been accelerated by human actions. Antibiotic drugs are overprescribed, used incorrectly, and applied in the wrong context, which expose bacteria to more opportunities to acquire resistance mechanisms. This starts with healthcare professionals, who often prescribe and dispense antibiotics without ensuring they are required. This could include prescribing antibiotics to someone with a viral infection, such as rhinovirus, as well as prescribing a broad spectrum antibiotic without performing the appropriate tests to confirm which bacterial species they are targeting. The blame is also on patients, not only for seeking out antibiotics as a “cure-all” when it’s not necessarily appropriate, but for poor patient adherence and inappropriate disposal. It’s absolutely imperative that patients follow the advice of a qualified healthcare professional and finish antibiotics as prescribed. If a patient stops dosing early, they may have only cleared out the antibiotic-susceptible bacteria and enabled the stronger, resistant bacteria to thrive in that void. Additionally, if a patient incorrectly disposes of leftover antibiotics, they may end up in the water supply and present new opportunities for bacteria to develop resistance.

Overuse of antibiotics in the agricultural sector also aggravates this problem, because antibiotics are often obtained without veterinary supervision and used without sufficient medical reasons in livestock, crops, and aquaculture, which can spread the drugs into the environment and food supply. These contributing factors to the rise of antibiotic resistance can be mitigated by proper prescriber and patient education and by limiting unnecessary antibiotic use. Policy makers also hold the power to control the spread of resistance by implementing surveillance of treatment failures, strengthening infection prevention, incentivizing antibiotic development in industry, and promoting proper public outreach and education.

While the pharmaceutical industry desperately needs to research and develop new antimicrobials to combat the rising number of antibiotic-resistant infections, the onus is also on every member of society to both promote appropriate use of antibiotics as well as ensure safe practices. The World Health Organization has issued guidelines that could help prevent the spread of infection and antibiotic resistance. In addition, World Antibiotic Awareness Week is November 13-19, 2017, and could be used as an opportunity to educate others about the risks associated with antibiotic resistance. These actions could significantly slow the spread and development of resistant infections and encourage the drug development industry to develop new antibiotics, vaccines, and diagnostics that can effectively treat and reduce antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Peer edited by Sara Musetti

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: