Author note: This article was co-authored by Jessica Lin, a rising high-school senior and KQED Youth Advisor passionate about mental health and behavioral science. The data and views presented in this article are not reflective of the opinions of our institutions. The reporting is meant to present the data on the current state of the academic climate and its impact on the mental health of trainees from underrepresented backgrounds.

Banana trees, for which Dr. Hernandez names her debut book after, were transplanted from the South Pacific and Southeast Asian regions to the Americas via colonial European ships – forcing the plants to adapt to less than welcoming environments. In discussing the necessity of the inclusion of Indigenous voices in the environmental “conservation” discourse through her book, she also shares her experiences and knowledge being dismissed in the scientific academic sphere, invalidating Indigenous knowledge.

The themes of displacement, dismissal, and invalidation raised in this book are far-reaching beyond the field of environmental sciences or the author’s experiences as an Indigenous woman with roots in Mexico and El Salvador. The current climate of academia, higher education, and the sciences – especially in today’s America, is not conducive for the success of individuals of historically excluded and/or minoritized backgrounds. If rich diversity in the environments we cultivate benefit the ecosystems of our society, why are academic landscapes inhospitable for trainees from these groups? How can those who have enjoyed the bountiful fruits served on the leaves from these displaced banana trees neglect the harsh environments in which they endure? Rather, how can institutions built on the labor and innovation of historically excluded groups relish in their contributions without safeguarding their well-being?

On Thursday, June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States of America (SCOTUS) ruled to strike down race-based Affirmative Action, a policy meant to combat the historic discrimination against Black students and other minoritized individuals in college admissions. This court decision has abolished race-conscious admissions for every college across the United States, with some analyses projecting about a 10% drop in Black and Hispanic enrollment across the nation in upcoming admissions cycles. Empirical evidence from California, the largest state to ban race-conscious admissions, has cited a 30% to 40% drop in Black and Hispanic enrollment after selective institutions eliminated race as a consideration in admissions.

More concerningly, the ripples of this ruling will impact far more than admissions. Many administrators at academic institutions will apply this policy to all other race-related programming, threatening college preparation programs for Latino students, cutting funding for predominantly Black student organizations, preventing the creation of cultural centers, and censoring the creation of African American studies and curriculum. Reduced numbers of Asian American, Black, Indigenous, Latinx, multiracial, and Pacific Islander persons on campuses will exacerbate feelings of isolation, erasure, and unimportance leading to higher turnover rates.

“It wasn’t perfect but there’s no doubt it helped offer new ladders of opportunities for those who, throughout (United States) history, have too often been denied a chance to show how fast they can climb” – Michelle Obama

The ruling is most relevant to the most selective US universities, which receive significantly more applications than admission spots available – the same institutions that train most researchers and the next generation of those in science, technology, engineering, math, and medicine (STEMM). Heightened discussions around race-conscious admissions at the college and graduate education levels begets questions about talent retention and development. What happens to the students of minoritized identities after admission and enrollment? Efforts to increase the number of students from diverse backgrounds and identities do not mean much if there are not supports and resources in place to help students navigate systems built to exclude them.

THE BENEFITS OF DIVERSE PRACTICES

Including as many sectors of the population as possible in our universities and academia ensures a sustainable future for research that is truly representative of the racial, ethnic, and economic diversity of society. A diverse workforce that brings together various different perspectives is better equipped to pursue questions and problems that transcend the small sector of humanity that has been historically well-represented in research and the biomedical sciences. Beyond expanded innovation and increased productivity, there are moral and ethical reasons for developing an equitable and inclusive research environment. Gender and culture as examples also influence the scientific questions that are pursued in addition to the approaches taken to scientific phenomena. Although the pertinent notion is that science is an exacting and apolitical space, scientists do not check their beliefs and biases at the door. Valid science should be more than just including appropriate controls and replicates – it must be conscientious to the interests and challenges of all sectors of society. Research conducted by predominantly white, middle-class scientists will lead to studies conducted primarily on white middle-class populations, which could lead to conclusions that are not as applicable to broader populations. Thus, it is not a matter of including these groups in higher education and academia on the principle of being different, rather on recognizing their unique individual strengths and how to synergize these qualities for the advancement of society as a whole.

Examples of the scientific questions that benefit from diverse research conduct:

- Western research often uses blood and tissue from white individuals to screen drugs and therapies but little is known about that on people from different ethnic groups.

- Different ethnic groups may present with different gene variations or varied allele frequencies which can influence the efficacy of certain pharmacotherapies to prevent coronary artery disease and/or the appropriate dosage of the therapy

- All early primate behavior studies were conducted by men leading to male primatologists adopting Darwin’s view of evolutionary biology centered around competition among males for access to females. Only later when female biologists studied primate biology was it discovered that there was a new scope on maternal reproductive strategies.

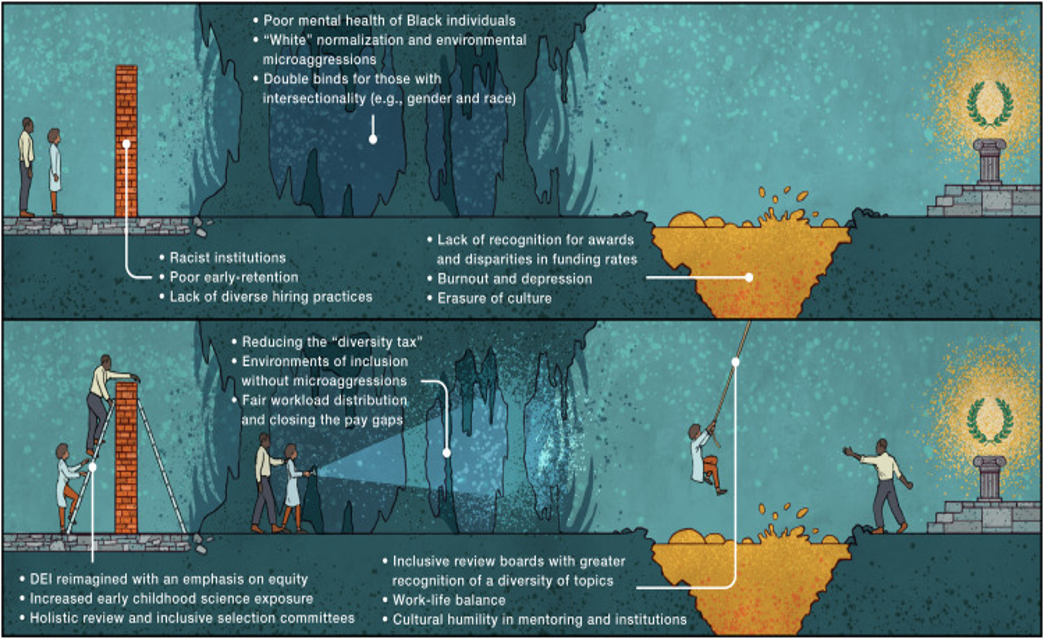

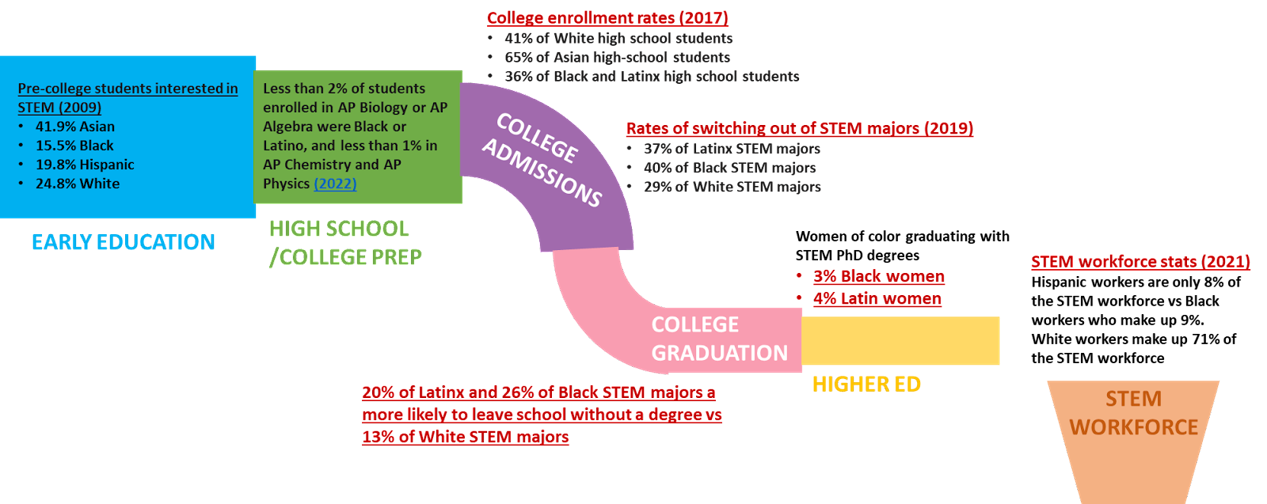

THE INHOSPITABLE ACADEMIC ENVIRONMENT

Despite the striking evidence supporting the benefits of a diverse and inclusive biomedical field, various barriers exacerbate disparities established by exclusionary academic practices with little action to change discriminatory systems. Professors of Color across top US universities have expressed witnessing other professors at these institutions following the misguided perception that students of color are not as interested or talented as white students. Though these beliefs may not be held by all professors in these institutions, external perceptions of students’ value impacts their self-perception and thus their self-efficacy in pursuing their academic and professional endeavors. Despite making up one-third of the US population, less than 15% of doctorate degrees are earned by underrepresented scientists. Data collected from the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 2017 concluded that of the 23.89% of women of color in US STEM graduate programs, only 11.96% of US STEM PhD recipients were women of color. Beyond the milestone of obtaining a doctorate, Black scientists still continue to suffer lower pay as compared to their white colleagues, lesser access to resources, fewer advancement opportunities, cultural erasure, undervalue, isolation, stereotype threat, and tokenism.

An article authored by five African American Ecology and Evolutionary Biologists further emphasizes that “reiterating notions or meritocracy and correct academic behavior do not dismantle oppressive systems” and that true diversity does not require assimilation from Black, Indigenous, and other scientists of color. The aggregate of these burdens on minoritized scientists has severe consequences for their mental health. In situations where the mental health of an individual is not prioritized, it is likely that these scientists will ultimately leave their institutions resulting in a loss of diversity and talent. Reports on the impact of research culture on the mental health and diversity in STEM identify key features of the research culture and environment that affect scientists’ ability to function and thrive in their research environments. Bullying and harassment, to which scientists from historically excluded groups (people of color, disabled individuals, LGBTQ+ members, women) experience at increased levels, was reported to have been observed by 74% of postdoctoral staff. Despite 60% of researchers attributing this behavior to their manager/supervisor, 48% of respondents report that their institutions lack a policy on this.

Forms of bullying and harassment in the research setting is often more nuanced than supervisors shouting at their trainees (although this is an unfortunate reality in some labs). These abuses of power and exploitation of trainees can present in the forms of microaggressions, threats to withhold reference letters and/or funding, not giving credit for the intellectual property or work of the trainee, exclusion from events, cutting access to resources within and outside of the lab and/or program, discouraging professional development and career exploration activities, denying reasonable vacation time requests, or delaying PhD submission to retain expertise or for other undisclosed reasons.

THE IMPACT OF THE CURRENT ACADEMIC CLIMATE ON HIGHER-ED TRAINEES

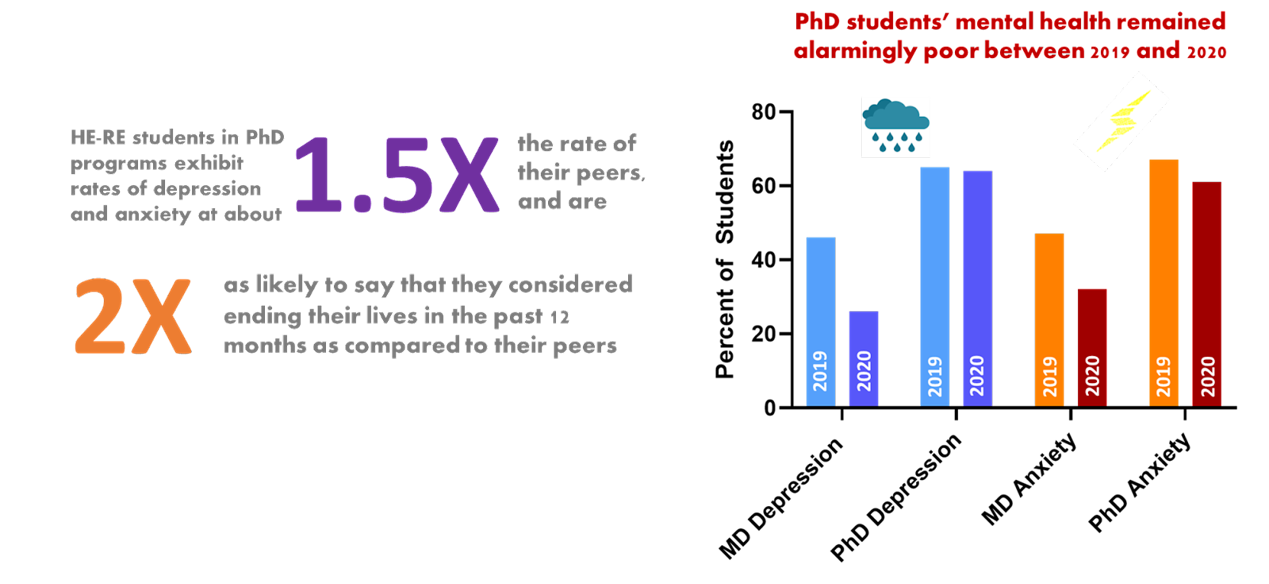

A recent study conducted on biomedical graduate students and medical students at UNC-Chapel Hill reported striking results on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and racial protests on the mental health of trainees. The study, which included survey responses from 957 students in medical and/or biomedical graduate degree programs, found that biomedical doctoral (PhD) students show greater incidence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation than medical students. Furthermore, across both training practices, historically excluded students (people of color, women, LGBTQ+ individuals) show higher incidences of heightened rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation than their peers.

Considering that across both programs historically excluded groups on the basis of race and ethnicity reported higher rates of mental health issues which were exacerbated by the pandemic, these key differences further raise concerns regarding toxic work environments, systemic racism, sexism, and unhealthy cultural and academic norms.

Further work on the impact of COVID-19 on Black students and academic staff in UK and US higher education describes the matter of inequity and injustice as “being in the same storm, but not all in the same boat”. Ultimately, although every member of society was affected by the pandemic, systemic injustices that have weighed on Black and minoritized communities since long before COVID-19, further exacerbated the disparities that impacted every day life. Emerging themes from this study included i) the pandemic within the pandemic (racism within COVID-19), which included sub themes of racial (re)traumatization and loneliness & isolation; ii) job precarity; iii) exploitation of Black labor. Staff and student surveys showed significant correlations and continuation of racism experiences across the academic landscape, underscoring the necessity to make more and culturally responsive connections between mental health service users and providers.

FROM WHERE DO THE ISSUES STEM?

This exodus of diverse talent has often been described as the ‘leaky pipeline’: a metaphor describing how women and people from minoritized groups are progressively lost from STEM subjects at each stage of the educational system – from primary school to high school then university, and ultimately reduced diversity across STEM careers. Despite the literature reporting higher rates of interest in STEM by racially minoritized students (RMS), high school graduation rates and college enrollment rates were lower for Black and Latinx students as compared to their peers in 2016. The disproportionality of these students’ participation in STEM may be attributed to the access to resources in K-12 education such as weak curricula, less qualified instructors, organizational features of the school, modest funding, and relationship dynamics with instructors. Districts in the US with the most Black, Latino, and Native students receive substantially less revenue, impacting the quality of education and access to resources for students of color. For example, although students who took AP/college-level courses during their high school years reported better preparedness for their STEM majors, within-school racial segregation and the lower likelihood that secondary schools attended by RMS offer these types of courses results in reduced participation in these programs for RMS. Furthermore, a common theme in the literature identifies that the nature of interactions RMS have with their education system critically impacts their STEM success. Hostile pre-college education climates undermine student progress, thus interests in STEM, self-efficacy, confidence, STEM identity, sense of belonging, enjoyment of math and science, and engagement are some of the key factors associated with Black and Latinx students’ STEM outcomes.

Cited studies include: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

MENTAL HEALTH DISPARITIES IN YOUTH PURSUING STEM

Mental health disparities may have a hand in the lack of diversity in STEM. In 2023, Mental Health America stated that 16.39% of youth from ages 12-17 experienced at least one major depressive episode in the past year, with the highest rates among youth who identified as more than one race, around 16.5% (about 123,000). Among minorities, Hispanic and Black youth had higher chances of showing mental health symptoms such as anxiety and/or depression, with Hispanic/Latinx youth reporting 51% and Black youth 50%. White and Asian American youth reported lower percentages; however, their rates were still high at 47% and 38%, respectively.

In the US, only 28% of youth with severe depression received consistent treatment, with 60% of youth with severe depression not receiving any care at all. According to NIH, 96% of studies reported barriers preventing youth from seeking care included limited mental health knowledge, 96% of studies stated other barriers included social factors such as social stigma and embarrassment, 68% expressed youth’s lack of trusting an unknown professional and confidentiality, and 58% reported the financial barriers of mental health care. Furthermore, in 2023, reports stated that 1 out of 10 youth (over 1.2 million) covered under private insurance still don’t have coverage for mental health care, with a therapy session in the U.S. costing on average $100-$200, according to Psychology Today. A price point that is unsustainable for most, as 27.3% of African American, 22.3% of Hispanic/Latinx, 26.3% Native American, and around 8.5% of White and Asian youth (under 18) live in poverty as of 2021, according to the U.S Department of Justice.

Among ethnic and racial minority youth, socioeconomic disadvantages contribute significantly to mental health difficulties. These youth experience stressors such as poorer education, housing, unsafe neighborhoods, and frequent experiences of discrimination, racism, and oppression. Racial trauma stemming from microaggressions to blatant racism can cause one to question their self-worth and lower their esteem. Additionally, parents may have to work multiple jobs to keep the family afloat, resulting in less time spent with children doing activities which can most likely affect the child’s development. The American Psychological Association stated that the consequences of these conditions may lead to low self-esteem and constant stress, damaging their mental health.

In a study on racial and ethnic differences in depression, major depression affects minorities differently than non-Hispanic white people. People of color are more likely to experience chronic, prolonged, and disabling depression affecting functionality, whereas they are less likely to experience acute episodes of major depression than white people. With the costs and stigma of mental health care, adults like youth are uncared for.

Although social media and the internet have pushed mental health awareness to become more normalized, cultural or religious differences can prevent minority youth from seeking help. Within the Asian American community, social norms often include shame around poor mental health and a lack of open conversations about emotions leading to high rates of Asian American suicide and poor mental health in young adults. Other minority groups similarly experience the same, with many believing that previous generations experienced tougher trauma, invalidating their own emotions or struggling with the cultural differences and values of being a certain ethnicity while being an American. For example, in many Asian cultures, youth grow up emphasizing family, whereas the American culture they take part in outside their family is more individualistic.

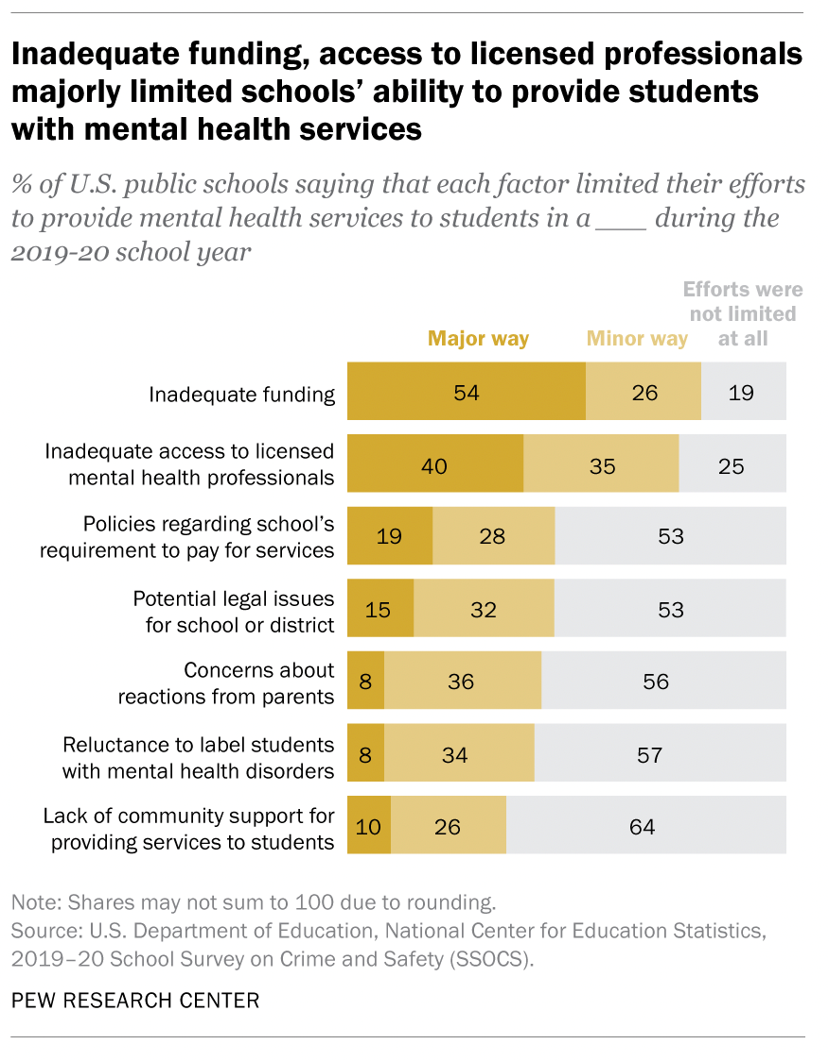

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) School Survey on Crime and Safety, during the 2019-20 school year, only 55% of U.S. public schools provided licensed diagnostic mental health assessments to evaluate students for disorders, and only 42% of K-12 schools offered treatments such as medication, counseling, or psychotherapy. Funding and access to licensed professionals limit a school’s ability to provide students with mental health services, often causing students in underprivileged areas to receive inadequate or no help in a place that is supposed to support and educate them.

Pew Research Center graph displaying barriers to access to mental health services in US public schools.

But how does mental health have an impact on diversity in STEM? Mental health can have a detrimental effect on youth and, with that, their education. Without treatment, it can lead to children being absent, suspended or expelled, or just unhappy at school, causing their learning to be negatively impacted. Mental health can also increase the risk of drug use, violence, and sexual behaviors, leading to HIV, STDs, and unintended pregnancy. If a student isn’t doing well mentally and academically they are less inclined to pursue higher education. Only 32% of students with serious mental illness continue to postsecondary education, as many drop out due to anxiety and depression. Often racial and ethnic minority students are disproportionately more at risk for mental health issues with less accessibility to proper resources. Research stated by the National Association of School Psychologists shows that students who receive social-emotional and mental/behavioral health support achieve better academically because it ensures that mental and behavioral health problems don’t affect the development of classroom engagement but also relationship and work-related skills in the long run. These skills benefit the students as they prepare to become independent. Mental health resources and care, especially for all youth, should be more affordable and accessible so that youth can thrive inside and outside the classroom.

CONCLUSIONS

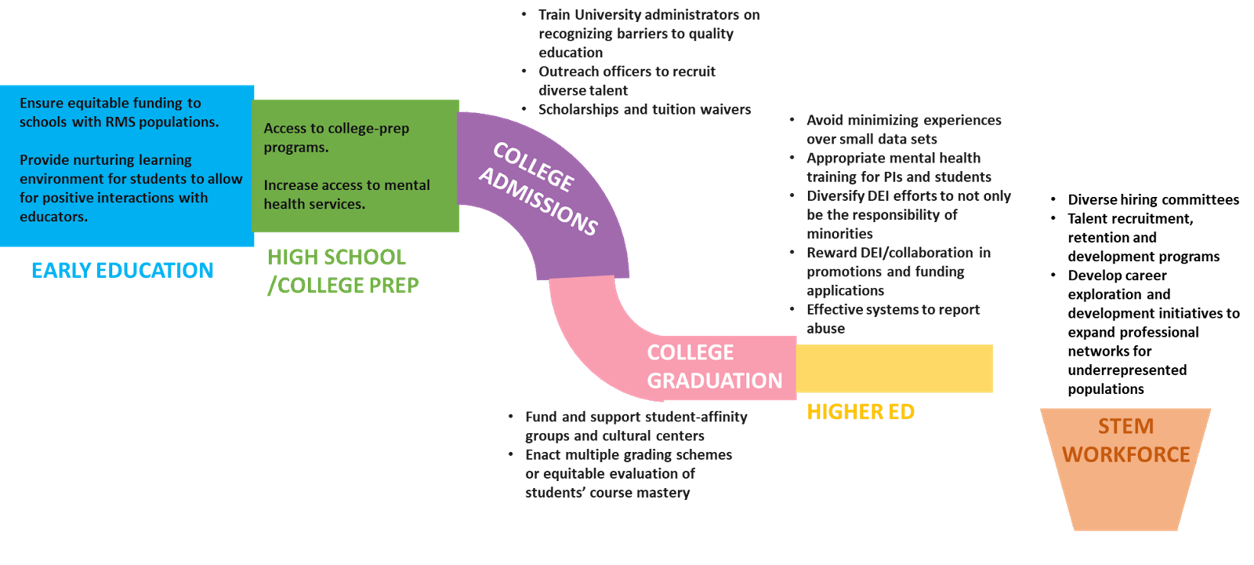

Considering that STEM occupations are among the highest paid and most prestigious professions, barriers to accessing positions in the STEM fields will translate into exacerbated disparities in income, status, and power inequalities, disproportionately impacting racially minoritized individuals and those of other minoritized identities in the broader scope of society. Although race-conscious admissions are currently at the forefront of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) discussion, institutions must also be held accountable for delivering on their mission to foster the success and prosperity of each rising generation, keeping in mind the increasingly diverse landscape.

Making the necessary actionable changes to create an inclusive culture in academic training and STEM professions requires more than just increasing the number of students from historically underrepresented and excluded groups or one-off initiatives. The momentum to build diversity crucial for success demands ongoing support, mentorship, and governance.

At the level of pre-college education, it will be crucial to ensure equitable funding to schools with higher RMS populations thus ensuring access to college preparation and STEM success programs. Furthermore, recognizing the impact of the educational environment on mental health, self-efficacy, and student success, increasing instructor diversity, providing quality training for supporting diverse students academically, and increasing access to cost-free culturally responsive mental health services will be crucial for pre-college student success.

With respect to college admissions, universities are being suggested to train faculty and senior administrators on how to recognize the barriers students have faced in seeking quality education and to consider measures of adversity to build inclusive and diverse student bodies. Universities can also staff outreach officers as part of recruitment initiatives to scout talent from underserved populations and reduce the financial barriers of attending prestigious colleges by offering scholarships or tuition waivers for families earning under a certain income. RMS are more likely to persist and thrive in STEM when surrounded by peers who can provide supportive social and academic environments.Therefore, it will also be crucial to ensure funding and support for student-affinity groups and cultural centers that create safe spaces for diverse student communities. Student success can also be addressed through mastery-based grading or the “multiple grading schemes” method, which can serve as a way to eliminate biases in traditional grading that have posed barriers for students of color and those from lower-income backgrounds. This method would prevent grades from being affected by factors in students’ after-school life that they may not have control over which would prevent them from completing their homework.

Finally, recognizing how integrated research and training environments are for PhD and/or MD students with their personal lives and mental health, academia must be restructured to eliminate discriminatory and toxic practices and increase accountability for ensuring the well-being of trainees. When a small percentage of individuals in these programs express issues with the research culture it can be easy to overlook these concerns, but institutions must avoid minimizing experiences over small data sets. Mental health training must engage both Principal Investigators and students and be facilitated by trained professionals who are aware of and sensitive to the nuances of graduate training and the experiences of minoritized individuals. Mental health resources and treatments for trainees should also be accessible, low to no-cost, and of high quality (including culturally-conscious counseling). Furthermore, the efforts to create inclusive research environments and ensure mentorship and sponsorship for students from underrepresented backgrounds should not depend on the efforts of historically excluded and marginalized groups. All faculty and staff should buy-in to changing the climate of academia and the system should require and reward DEI efforts such as acknowledging DEI work and collaborative research and weighing diversity efforts into all promotions/tenure decisions and funding decisions. Additionally, structured accountability must be implemented to ensure that efforts are effectively carried out and adjusted accordingly based on feedback. Formal reporting routes for bullying and harassment must be established and allegations need to be taken seriously with followed by timely action that ensures protections for the reporter.

To continue to normalize abusive and exploitative academic practices while dismissing trainees from historically excluded and minoritized backgrounds with the sentiment that “you grow through what you go through” is comparable to attributing a poor harvest to droughts while actively salting the earth. The illusion of exclusive meritocracy is not only a barrier to equity, but it also continues to hinder society’s advancement as a whole. The time is ripe to reflect on academia’s roots in structural oppression and move toward cultivating an ecosystem that not only protects the mental health of all trainees, but also ensures and celebrates their successes.

Peer editor: Aditi Kothari