Historically and today, female participants and animal subjects have been underrepresented in the majority of scientific research. Leaving out females doesn’t just hurt women, it affects the rigor and validity of science as a whole.

Here’s a fun trivia question – when did United States law first require clinical trials to include women in their pool of participants: 1977, 1985, 1994, or 2016? If you guessed 1977, you guessed wrong; that was the year that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) effectively did the opposite by banning women from participating as participants in clinical trials at all. In their “General Considerations for the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs”, the FDA excluded women with “childbearing potential” (defined as “a premenopausal female capable of becoming pregnant”) from participating in Phase I and II clinical trials; however, this policy change appeared to have a dampening effect on the participation of women in clinical trials across the board. This decision was not reversed until 1994; since then, the FDA has updated their guidelines to emphasize the need for female participants and the enrollment of women in any clinical trial funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is now required by law. But with only 25 years of catching up, many areas of biomedical research are still in the dark when it comes to the effects of illnesses and treatments in female patients. And lest we assume that this legislation eliminated the exclusion of women from clinical trials, only last week (October 4th, 2019) the FDA approved the HIV prevention medication Descovy despite the manufacturer presenting data from clinical trials that explicitly excluded people who have receptive vaginal sex.

Clinical research has developed a blind spot for female participants

The exclusion of women from clinical research was in part a response to the toxic effects of medications like thalidomide on developing fetuses. The NIH and FDA wanted to limit the potential for investigational drugs to cause birth defects. However, the decision to exclude all women, not just pregnant ones, also speaks to a long-standing opinion in science that males represent the “normal” or “default” biological situation and that females are “complex” (often the most charitable description). These agencies didn’t seem to appreciate that they would be missing useful information by focusing solely on men.

Today, many common medications have been studied almost entirely in men prior to receiving FDA approval. Phase 1 clinical trials (the first step in seeking FDA approval for a new medication, designed to test the safety of a drug) still recruit far more men than women, in part because people using hormonal contraception are often excluded from recruitment. This leaves researchers blind to sex differences in side effects of medications, which are often more serious in women. Recently, the FDA had to lower the dosage of the sleep aid Ambien in women because their slower metabolism of the medication was leading to an increased risk of serious side effects (including driving while asleep), a fact that was missed in the clinical trials for the drug. Even when women are included in clinical trials, the results are often not analyzed for the effects of sex, which prevents researchers from catching on to important sex differences.

Basic research to understand the symptoms and underlying pathology of common illnesses also suffers from a lack of female representation. Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death in both men and women in the US, but women may experience different symptoms of a heart attack than men do, which may in part explain why the survival rate for women is lower than for men. Research on the effects of daily low-dose aspirin found that it reduced the risk of heart attack, but the 20,000 person study didn’t include a single woman. When a follow-up study was conducted years later, aspirin did not have the protective effect in women that had been observed in men. Despite these facts, recent investigations of new cardiovascular drugs have still primarily recruited men. This disparity in female versus male recruitment can even be seen in illnesses that disproportionately impact women, such as Alzheimer’s disease, lung cancer and psychiatric illness. The refusal to see women as valuable research participants continues to leave them vulnerable to unexpected consequences of illness and treatment.

From the lab to the clinic

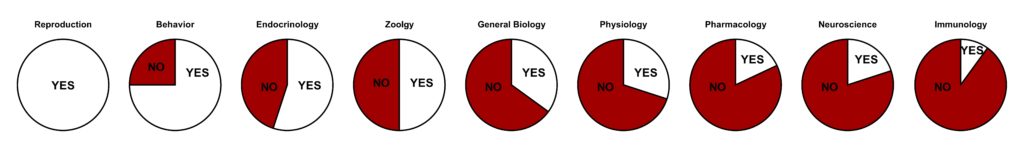

The focus on males in medical research extends all the way to the most basic scientific research: those using cell and animal models to study the development and treatment of disease. The vast majority of preclinical research has been carried out in male cell lines and male insects, rodents and primates.

White slices indicate the percentage of studies reporting sex differences, red slices indicate studies that did not analyze for sex effects.

Data from Beery and Zucker 2011, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. Visualization by Abigail Agoglia.

The justification for this approach was based on rhythmic fluctuations of hormones in female tissues; because female mammals have a fertility cycle with periods of higher and lower estrogen and progesterone, it was believed that data from female subjects would be more variable than data collected from males. The evidence to justify this claim has been inconsistent at best, and a recent meta-analysis of more than 300 neuroscience experiments showed that data from female mice were no more variable than male mice across a wide variety of physiological, behavioral and cellular measures. Male animals and humans have hormonal fluctuations too, and these changes do regulate cellular function and behavior; they just don’t occur as predictably as female fertility cycles do.

As of 2016, the NIH now requires that all new grant applications include the use both male and female subjects or justify the exclusion of one sex. But opinions about the merit of including females in preclinical research are still divided; even some members of the grant reviewing organizations at the NIH have expressed skepticism about the new policy:

“…this is nonsense…requiring it stands in the way of making progress…The policy introduces a variable that cannot be adequately controlled for with typical budget and capacity constraints and weakens rigor of the majority of applications.”

-Anonymous NIH study section member on the inclusion of female subjects in preclinical research

Still, valuable insights have been gleaned from including female subjects in accordance with NIH policy. Recently, developments in rodent models of pain biology are beginning to suggest biological reasons for the increased rates of chronic pain in women, and work to improve modeling for anxiety disorders in female rodents may enhance the ability of findings from these animal models to translate to human therapies.

Overlooking data

These concerns touch on a necessary consideration in the effort to be more inclusive of women as participants in scientific research: which “women” are we talking about? As with all forms of oppression, the exclusion of female participants in research is intersectional, disproportionately impacting women who are members of other underrepresented groups such as women of color, queer women, elderly women, transgender women and transgender, intersex or nonbinary people who were assigned female at birth (AFAB). The effects of this exclusion are felt most acutely in these communities, and these groups often suffer from a lack of representation even in forms of medical research that are aimed at women’s health issues. A horrifying recent example is the startling disparity in childbirth complication rates between white and African American parents in the United States. African American people are more than three times more likely to experience potentially life-threatening conditions like eclampsia (seizures due to elevated blood pressure) and blood clots during and after childbirth. Doctors who have been educated and trained primarily on white people are often ill-equipped to recognize these conditions in people of color and may delay treatment until it is too late. Research to understand why African American people experience higher rates of eclampsia has thus far been lacking.

Excluding these diverse populations of women and AFAB people from health research not only hurts the excluded parties, it impedes the progress of science in general. Sex and gender differences in how illnesses manifest and how treatments work provide an opportunity to explore aspects of disease that might be hidden if the focus is on one sex or gender group alone. The influence of hormonal signaling or the role of social factors on the progress of illness can tell us a lot about the underlying process that drives the disease. This information can suggest new strategies for treatment that can be effective in patients of all genders, not just women. Comparing men and women, male and female animals, pre and post-menopause people, or people who use hormone products and those who do not has the potential to provide these critical insights. When we limit our participant pool to only a certain section of the population, we miss valuable data.

Increasing the participation of women and AFAB people in clinical trials and preclinical research isn’t a fast process. The pace of research is often excruciatingly slow, and major changes in policy often take years to manifest results. Science and medicine as a whole have to work to rebuild trust and confidence with communities they have marginalized, especially women of color, queer women and transgender people. Investment in the analysis of how well diversity measures are working and continual refinement of policy is crucial to ensure that proposed changes are working as intended. The role of hormones in various clinical setting could use a revisit, especially when they pose a barrier to female subjects in preclinical animal experiments and exclude the millions of people who use hormonal products from clinical research. If you’re female or AFAB and interested in being a participant in a clinical trial, ask your doctor about ways to get involved in your area. Female participation in clinical research doesn’t just benefit women, it improves the understanding of disease in a way that can help everyone.

Edited by Candice Crilly and Aldo Jordan. Graphic by Alison Earley.

There needs to be inclusion of women in clinical trials to get an understanding of clinical trials

The science that informs medicine – including the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease – routinely fails to consider the crucial impact of sex and gender. This happens in the earliest stages of research, when females are excluded from animal and human studies or the sex of the animals isn’t stated in the published results. Once clinical trials begin, researchers frequently do not enroll adequate numbers of women or, when they do, fail to analyze or report data separately by sex. This hampers our ability to identify important differences that could benefit the health of all.

Thank you for writing this blog. This blog is very informative and valuable with deep explanation.

Thank you so much for sharing all this wonderful information !!!! It is so appreciated!! You have good humor in your thread. So much helpful and easy to read!