Scientists have always had the herculean task of “proving” the truth behind their discoveries. This very dedication to the truth is what led to the rigorous scientific method. Scientists attempt to disprove their proposed hypotheses over and over again, meticulously combing through evidence, re-hashing ideas based on such evidence, and repeating the cycle. Ultimately, the goal behind science is to let the truth, or the data, speak for itself. Inherently truth is neither good nor bad. It simply is. However, it is human nature to only want to hear truths that already align with one’s own views – and this was exactly the case in 1982 when two Australian scientists, Dr. Barry Marshall and Dr. Robin Warren, discovered the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its tumultuous relationship with the human gut.

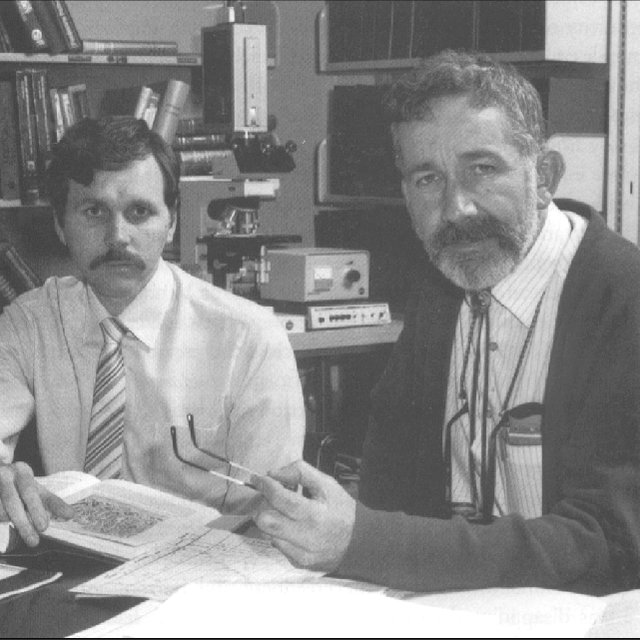

H. pylori is a gram-negative bacteria that can infect the human gastrointestinal tract. H. pylori infection is common, affecting around 50% of the global population. The bacteria primarily makes its residence in the stomach and most infections are asymptomatic. Often people do not even know they are infected. It wasn’t until 1979 when Warren, a pathologist at Royal Perth Hospital, was examining gastric biopsy samples from patients with peptic ulcers and gastritis when he noticed a large portion of the samples also contained an unknown, spiral-shaped bacteria. Warren became vexed by this unknown bug and was astounded to find no evidence of the swirly bacteria in healthy gastric samples. In 1981 during an internal medicine fellowship, Warren met Marshall, a practicing physician at Royal Perth Hospital, who became equally captivated by Warren’s swirly bug. Why was this strange bacteria present in gastric samples from sick patients with stomach ulcers, but not in the stomachs of healthy individuals?

Marshall was able to provide Warren with a wider array of gastric biopsies to investigate. As Warren perused these stomach snippets, Marshall began to isolate the mysterious bacteria. In 1982 they finally put a name to the little beast – H. pylori (formerly known as Campylobacter pylori). Together, Warren and Marshall published two papers in 1983 and 1984 detailing the discovery of H. pylori and its insidious link to gastric ulcers.

Despite finding that over 50% of the 100 gastric ulcer patients they initially screened had detectable H. pylori, their peers remained skeptical. Up until this time, gastric ulcers were largely believed to be caused by stress due to excessive anxiety or anger. Moreover, many believed that bacteria couldn’t grow in the harsh, acidic environment of the stomach. Warren and Marshall’s discovery was viewed as simply impossible.

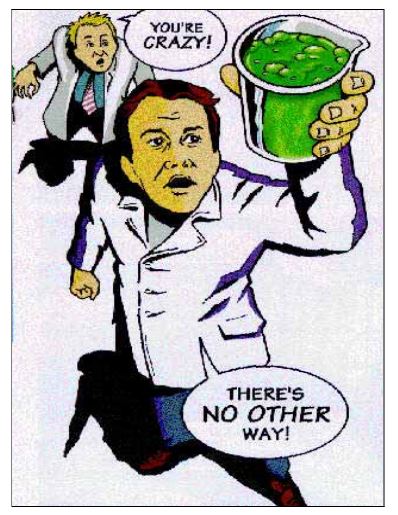

Despite the criticism, the pair continued to follow the spiraling trail of H. pylori. Marshall began a 7-year long clinical study, whereby he treated ulcer patients with antibiotics against H. pylori and noted that upon successful eradication of the infection, patients were relieved of recurrent ulcers. Following Koch’s postulates to determine if H. pylori was the cause of stomach ulcers, Marshall tried to infect lab animals and demonstrate it was a bonafide pathogen – not just a commensal bacteria in the right place at the right time. Unfortunately, his animal experiments were unsuccessful. This is when Marshall decided that the only way to truly test his hypothesis was to make himself the guinea pig.

Marshall, being a proper scientist, ensured that he had a baseline endoscopy before he brought a beaker full of cloudy, concentrated H. pylori broth to his lips. He then threw his head back and swallowed the bacterial tincture (yum!). After ingesting the bacteria, he assumed he would have to wait years before he would have evidence of resulting stomach ulcers. He was (un)pleasantly surprised when only three days later he developed nausea and a whopping case of halitosis. By day 5, he was very unwell and vomiting repeatedly. On day 8, he had a second endoscopy which revealed severe inflammation in his stomach. H. pylori was cultured from a biopsy during the second endoscopy, confirming it had set up shop in Marshall’s stomach. Two weeks after his first sip of the intoxicating bacterial brew, Marshall started antibiotics and began to recover from the infection. He published his findings in 1985, describing a “male volunteer’s” acute case of H. pylori-mediated gastritis.

Warren and Marshall’s hard work finally culminated in 2005 when they were each bestowed the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for identifying the link between H. pylori and gastric ulcers. Since Warren’s initial discovery of the screwy bug and Marshall’s famed self-experiment, scientists have discovered more links between H. pylori infection and gastrointestinal ailments, including stomach cancer. Their discovery has led to worldwide health impacts with the development of diagnostic tools and treatments for H. pylori. In Australia, it is estimated that the case rate of gastric ulcers has diminished by 70% since the discovery and saved the country more than $300 million annually in healthcare costs. H. pylori has even been eradicated in most developed countries and is now considered an “endangered bacterial species.”

That’s the story of how scientists drank bacteria and won a Nobel Prize. I should probably end by saying something like “don’t try this at home,” but if you have ever smelled a frothing broth culture of bacteria (or even just whiffed a stagnant pond), that’s likely deterrent enough. They wouldn’t possibly award another scientist for drinking bacteria… would they?

Edited by Mark Geisler