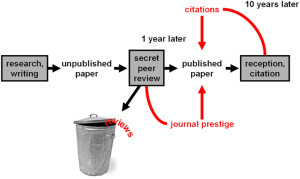

As many young academics very well know, science can bum you out. Experiments fail, equipment breaks, and funding opportunities are few and far between. Even when experiments run smoothly, the process to publish our research can be painstakingly long. In fact, a recent article published in Nature News and Comment revealed that the median review time for submissions to Nature has nearly doubled in the last decade.

With obstacles such as these decelerating advancements in our scientific careers, it’s easy to feel distressed and discouraged. Unfortunately, evidence is accumulating that these types of emotions have far-reaching consequences on our physical and psychological well-being. However, emerging research also shows that replacing negative thoughts with positive ones can not only improve our health and well-being, but enhance our productivity and ability to succeed at work.

You might be wondering – if negative emotions have such adverse consequences, why did they become a part of our cognitive repertoire? Negatively valenced emotions, such as anger, fear, disgust, and sadness, are actually thought to be a result of evolution. To survive in the wild, an animal must react to threatening situations, such as the presence of a predator or a toxic substance. Negative emotions cause the body to prepare, both physically and psychologically, to avoid that threat. Consider fear; when an animal comes into contact with a dangerous predator, fear-related brain regions such as the amygdala become active. These fear-associated regions send neurochemical signals to motor regions of the brain, triggering escape and defense behaviors that keep the predator away.

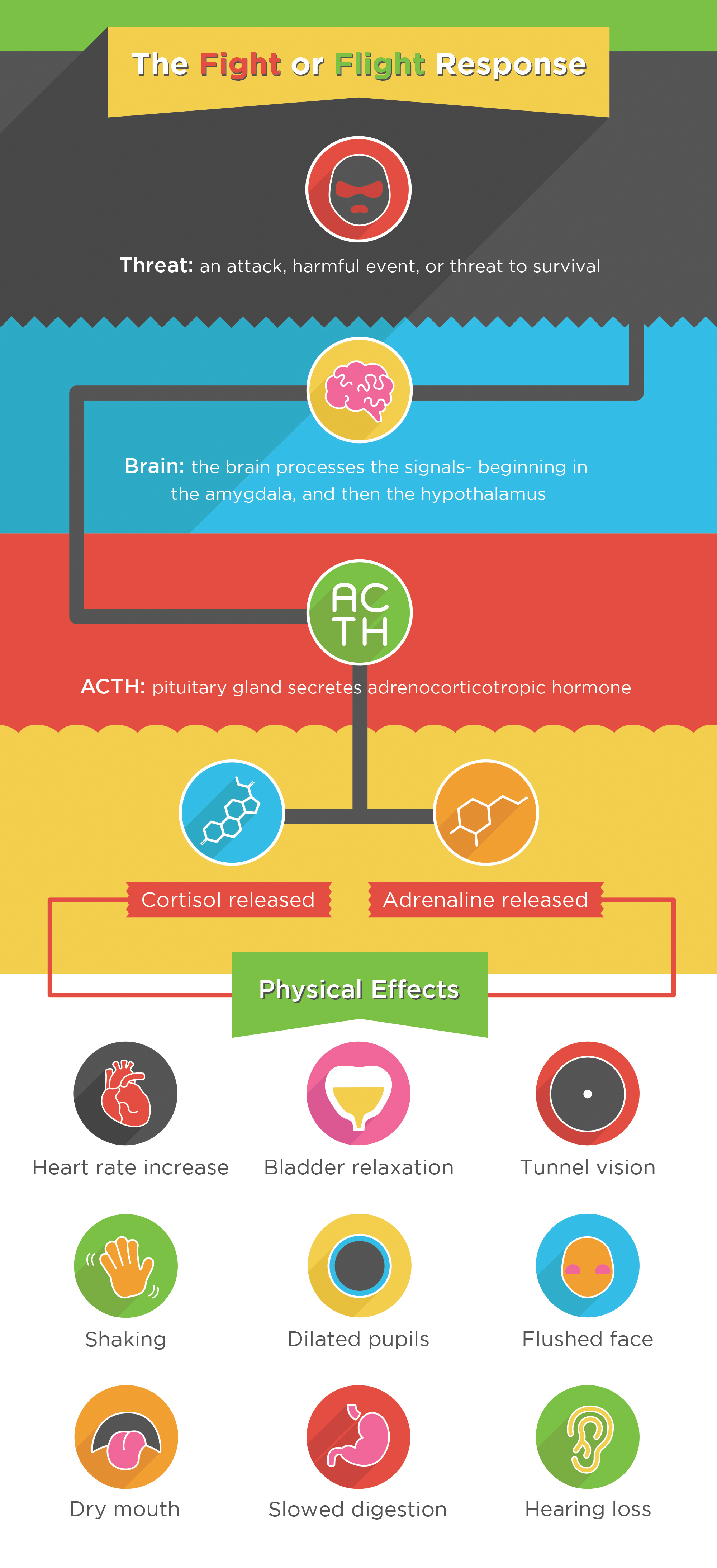

The reason these life-saving emotions eventually interfere with our health and well-being comes down to a phenomenon you’re likely familiar with – the fight-or-flight response. The fight-or-flight response is a mechanism by which our bodies translate negative emotion into deliberate action. In stressful situations, an alarm system in the brain known as the hypothalamus is set off. Lending support to the brain regions mentioned above, the hypothalamus sends out neural and hormonal signals that cause adrenaline and cortisol to be released in the body. Both of these stress hormones maintain the physiological processes necessary to fuel escape and defense behaviors. Under normal conditions, the fight-or-flight response eventually terminates and our bodies return to their resting state. However, when persisting experiences of negative emotions keep this system activated, the consequences can be serious. Disorders such as anxiety, depression, and cardiovascular disease have all been strongly linked to chronic stress and negative emotions. This may seem like bad news for academics, since perpetual stress is practically inherent to our daily lives. Fortunately, research suggests that positive emotions can not only counteract the adverse consequences of negative emotions, but also improve our long-term cognitive abilities and life-satisfaction.

Positive emotions like joy, serenity, contentment, interest, and love arise in situations that do not require immediate defensive action. For this reason, researchers have had trouble determining an explanation for the ability to experience these feelings. However, in a 2001 landmark publication, UNC’s very own Dr. Barbara Fredrickson conceived the “broaden-and-build” theory on the evolutionary purpose of positive emotion.  The broaden-and-build theory posits that since positive emotions are experienced in diffuse situations that do not require rapid action, our mental abilities temporarily broaden, allowing for higher-level thinking and wider-range ideas. This broadening of mindset allows an individual to recall, discover, and build mental resources to respond appropriately to the situation at hand.

The broaden-and-build theory posits that since positive emotions are experienced in diffuse situations that do not require rapid action, our mental abilities temporarily broaden, allowing for higher-level thinking and wider-range ideas. This broadening of mindset allows an individual to recall, discover, and build mental resources to respond appropriately to the situation at hand.

Let’s think about this more concretely, using interest as our prototypical positive emotion. When somebody’s interest is piqued, their mindset expands. They call on their attention, exploration, and memory resources to absorb new information and incorporate it into their existing knowledge. The benefits of this process may include enhanced memory, greater engagement, and better performance in school and at work. Dr. Fredrickson argues that the resources strengthened through repeated positive emotional experiences increase the odds of surviving and thriving. Put simply, positive emotions broaden our outlook in ways that rebuild who we are for the better.

Broadening and building our cognitive abilities by transforming negative situations into positive experiences has extensive benefits. Research indicates that frequent positive emotional experiences contribute to important life outcomes, such as friendship development, marital satisfaction, higher incomes, better physical health, and longer lifespans. An extensive review published in 2008 by Julia K. Boehm and Sonja Lyubomirsky of the University of California, Riverside, presents insurmountable evidence showing that positive thinking improves not only our health, but work performance as well.

A selection of the findings cited suggest that exemplary work performance by positive people transcends simply developing work-related skills and promotes altruistic, courteous, and conscientious behavior. As a result, positive people are more likely to exert extra effort, offer suggestions for improvement, and spread goodwill. Finally, positively-thinking people tend to show less burnout despite heavy workloads – an especially encouraging statistic for those enmeshed in the rigors of academia.

The evidence is hard to ignore: the best way for young academics to handle the demanding lives we lead is through frequent positive emotional experiences. In order for this to happen, it’s up to us actively transform stressful situations and negative emotions into positive perception. For tips on implementing positive thinking into your everyday life, check out this post by the Mayo Clinic, and get your broaden-and-build on!