It’s 2 A.M. and I awake to a low rumble. The sound grows until I am sure the pictures are going to fall off the wall and the ground is about to open and swallow me whole. In a moment of panic, I think “earthquake!” A whoosh of air fills the room followed by silence. A feeling of annoyance sets in as I realize there is no earthquake. It’s my roommate snoring.

You have probably found yourself in a similar situation at some point, as about 90 million people in the U.S. report snoring on a regular basis. Though often thought to be harmless, snoring can drastically disrupt sleep for both the snorer and their bed partner and negatively impact cognitive function and well-being. Despite snoring being a common issue in U.S. households, we know little about why some people snore and others do not. A new study confirms that lifestyle factors play a role, but also finds that mutations in certain genes may be another culprit.

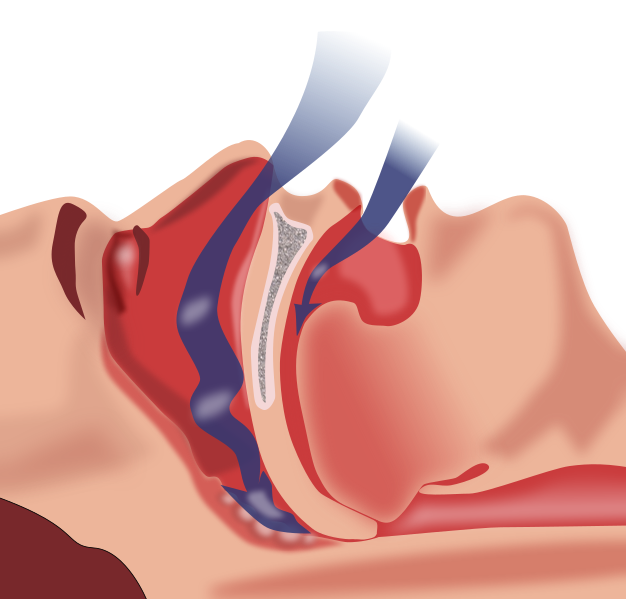

Snoring is caused by the narrowing of the airway which causes the tissue to vibrate during normal breathing. The narrower the airway; the louder the snore. In severe cases, the airway can become completely blocked and stop the flow of air entirely. This condition is called obstructive sleep apnea. A rarer form of sleep apnea, called central sleep apnea, occurs when the brain does not adequately control breathing during sleep. As you might expect, sleep apnea leads to sleep deprivation and can result in difficulty concentrating, depression, memory difficulties, and falling asleep during the day. If left untreated, sleep apnea can result in high blood pressure, heart attack, congestive heart failure and/or stroke.

Image credits: Habib M’henni

Aging, alcohol use, and obesity are some of the factors that increase snoring. Genetics also contribute to snoring, but the genes that are potentially involved in snoring have not been defined, until now. Researchers in Australia used a large collection of DNA samples from people in the United Kingdom. Each DNA sample also came with patient information such as lifestyle habits, socioeconomic status, and pre-existing conditions. Scientists found that men, smokers, alcohol drinkers, and patients of lower socioeconomic status were more likely to be snorers. Further, researchers suggest that increased body mass index (BMI), whole-body fat mass, and heart attack could directly, or indirectly, cause snoring.

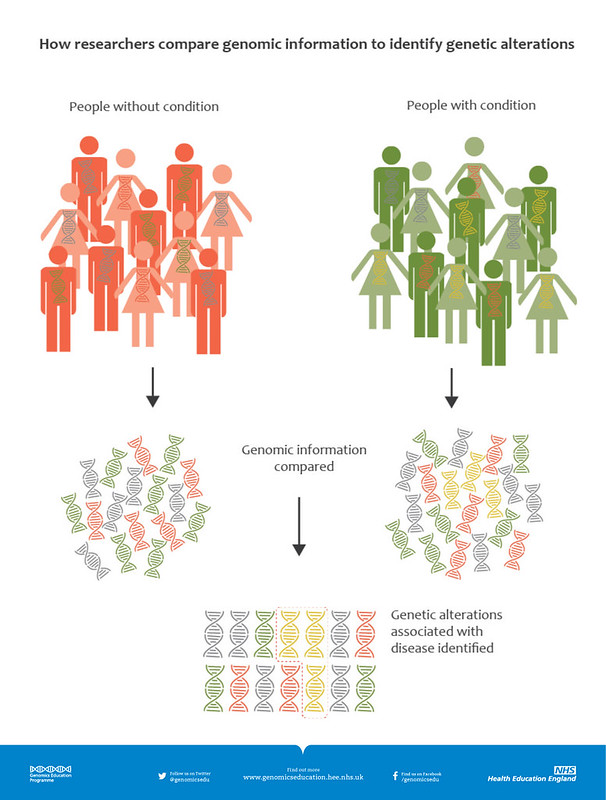

Next, scientists examined mutations in the DNA to see if mutations within or near certain genes were more common in snorers than non-snorers. 127 mutations were found more often in the DNA of snorers than non-snorers. Scientists predict that these mutations may ultimately change the levels of expression for 120 genes. Changes in the expression of one or more of these genes could make someone more likely to snore, than a person who expresses normal levels of these genes. Many of the genes predicted to be impacted by the snoring-associated mutations are involved in other cognitive, respiratory, psychiatric, and cardiometabolic disorders, or diseases concerning the heart and metabolism, like diabetes. All in all, this study shows that snoring is the result of interactions between many-body systems and might be a more complex sleep disorder than was originally appreciated.

Image credits: NHS HEE Genomics Education Programme

It is important to point out that most of the relationships identified in this study are only associations, which means that the genes and factors identified, except for BMI, whole-body fat mass, and heart attack, may not cause snoring. Additional research is needed to determine if changes in the expression of the identified genes lead to snoring. Further, all the participants in the study were of European descent. Snoring rates vary drastically by race. Therefore, it is possible the genes identified in this study may not be associated with snoring in individuals of non-European descent. Despite these shortcomings, this genetic study gives important insight into what causes snoring and may help eventually develop treatment options to save us all from 2 A.M. earthquakes.

Peer edited by Danielle Chappell