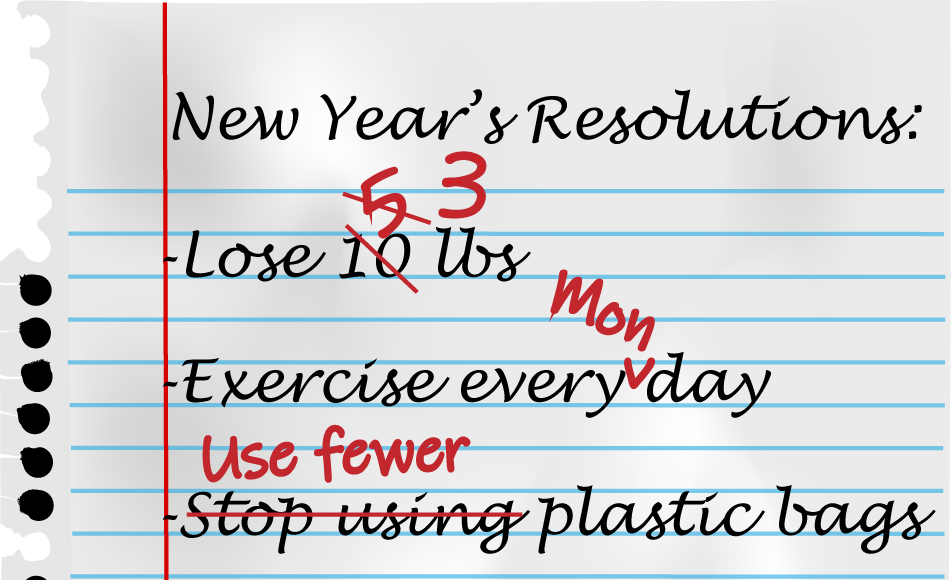

It was about this time last year that I found myself falling flat on the admirable New Year’s resolutions I had set. My daily yoga routine had evolved into a 30 second toe-touch in the morning and my new eco-friendly products were still in a shopping list on Amazon. As a 4th year graduate student all too familiar with failed experiments, I couldn’t stomach an unsuccessful project at home as well. Luckily, pursuing a PhD comes with strong problem solving skill sets. What is Step 1 of The Scientist’s Plan of Attack when faced with a problem? Turn to the literature to see if a solution has already been found. This is how I found myself in the societally constructed land where sad, desperate singles with three too many cats hang out: the self-help aisle at the bookstore.

Rather than using SciFinder to tease out quality sources, I turned to Goodreads to sort through books that could help troubleshoot my failed resolutions. My first self-help purchase was “The Willpower Instinct” written by Kelly McGonigal, a health psychologist. Professor McGonigal (Harry Potter fans rejoice) wrote the book based on a course she taught at Stanford about the science of willpower. After a few years of teaching and feedback from her students, she wrote this book outlining the currently accepted research associated with willpower, peppered in with some anecdotes from her students and how they applied the conclusions from these published studies to their own habits. Between the author’s credentials, solid reviews, and over 20 pages of references in the back of the book, this seemed like a good place to start.

It’s a year later, and I am now one of those people that goes around flinging self-help book recommendations to anyone who mentions a personal problem they’re having and constantly saying things like “this book changed my life”. But… this book changed my life.

McGonigal walks us through a series of published rat and human studies that identifies two separate parts of the brain that either experience anticipation of a reward or the pleasure from the reward itself. In other words, while the anticipation of binging Netflix sure feels more rewarding than anticipating 20 minutes of yoga, this book taught me to pay attention to how much pleasure each activity actually brought me. I immediately found that I felt happier and less anxious during and after yoga, while watching TV left me feeling less refreshed. After learning to be mindful of what I was anticipating versus actually enjoying, I had a better shot at ignoring the distracting anticipation of a television reward.

I also learned that I was using what psychologists call “moral licensing” to give myself permission to not adapt green habits because of the little things I did, like making a saved shopping list on Amazon or sharing articles on social media. She cites many studies demonstrating the ways consumers use small green actions to assuage their guilt for participating in more harmful behaviors. After realizing what I was doing, I took concrete steps to switch to reusable grocery bags and decline plastic straws at restaurants. However, I wouldn’t let that give me permission to make more wasteful decisions later in the day.

My new identity as a self-help book reader is a year old and I am still learning new cheat codes to navigating adult life with each addition to my library. However, the stigma of the genre makes my recommendations for others often fall on the ears of unwilling readers. My 2019 New Year’s resolution? Convince you, the reader, that this genre deserves a re-brand and a chance. As scientists we are trained to find reputable sources of information, and as graduate students we have a remarkably high chance of suffering from mental illnesses. Let’s use our skill set to find quality self-help books to add to our artillery of problem solving tactics that can be applied to ease some of these stresses that make it home with us after a long day in the lab. I hope to one day walk into the self-help aisle and see lonely, desperate singles with three too many cats and any other person who wants to be a proactive researcher and peruse the literature to find personal solutions to any minor problems they find themselves needing better resources to solve.

Peer edited by Rashmi Kumar.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: