Have you ever noticed a leather product marketed as “genuine leather” and wondered, “genuine compared with what?” Perhaps you compared genuine leather with plastic leather, or “pleather,” also known as faux leather or vegan leather, though this does not fully capture the range of products available on the market. In fact, “genuine leather” is a broad definition of goods, which includes split, top-grain, and full-grain leathers made from different components of animal hide. The lowest grade, split leather, refers to the part of a cow’s hide that has been split from the grain, creating a pliable fabric that can be reinforced with plastic coatings or painted with a glossy finish. At the other end of the spectrum, full-grain leather retains the unique characteristics, imperfections, and natural strength of the fully intact animal hide, and is therefore the highest grade of genuine leather money can buy. Investing in full-grain leather could pay dividends, as its durability justifies the cost for high-wear items such as belts, work boots, wallets, and handbags.

Though seductive marketing of high-quality cow leather goods may convince some to spend their hard-earned cash on a new pair of winter boots, there are massive downsides to genuine leather: subpar animal welfare and poor environmental sustainability. Raising and slaughtering cattle, as well as tanning of the animal skin, are water-, energy-, and resource-intensive processes. While faux leather is perhaps a more ethical alternative to leather, plastic is also detrimental to the environment. Plastic leather is derived from polyurethane, a synthetic material made from reacting alcohols with diisocyanates and other chemicals. Despite its useful applications in bedding, refrigerator insulation, car interiors and coatings, circuit boards, and medical catheters, polyurethane plastic is not biodegradable. However, researchers are working to improve recyclability.

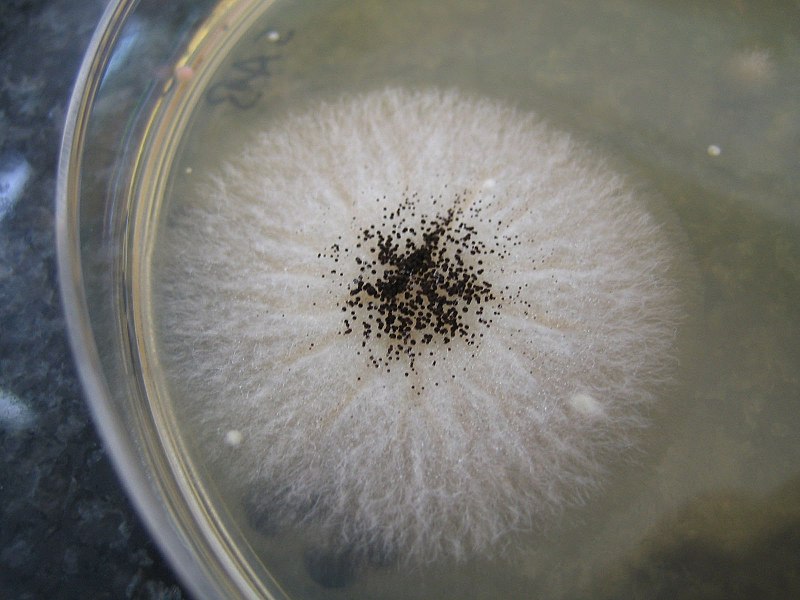

An attractive alternative to both animal leather and traditional plastic-based faux leather has recently gained attention: “mushroom leather.” Fungi have a root structure called mycelium, which can grow on organic material like sawdust or agricultural waste, thereby converting industrial byproducts into a mat of fungus. The mycelial mat can be grown to desired size and shape specifications, unlike leather which is limited by the size of the cow. Beyond customizability, fungal leather takes only weeks to grow, whereas animal leather requires years to produce. While the lifespan and strength of fungal leather have yet to be fully explored, preliminary results suggest that the durability is comparable to traditional cow leather.

If you’d like to get your hands on a piece of fungal leather, though, you might have to wait. The $400 handbag released in 2018 by Bolt Threads sold out in only seven days. However, investments and Kickstarter fundraising have been highly successful and are likely to bring fungal leather to market once production is scalable. In the meantime, conscious consumerism can improve your awareness of animal-based and faux leather sourcing and production methods and empower your search for eco-friendly investments.

Peer edited by Connor LaMontagne