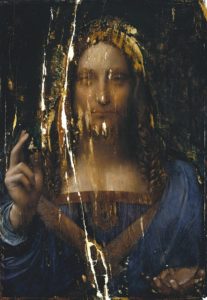

Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci painted around 1500

In the digital age of quarantine, I spend most of my day on YouTube. Whether it be listening to music, watching Trevor Noah handle the changing world, or just falling into a YouTube rabbit hole, I spend an unhealthy amount of time on the website. My most recent deep dive was into art restoration, specifically by Julian Baumgartner, who is part artist, part engineer, and a modern Renaissance man. Art restoration is, of course, art, but it’s equal parts science, which is elaborated on deeply by Baumgartner. It places him in a unique position of helping the future value of individual pieces by using science to restore their past damage.

Oil and acrylic-based paintings from the medieval ages and the high Renaissance must withstand 500–1000 years of damage. Whether that be light exposure, smoke and air pollution, humidity, mold, punctures and damage to the canvas, or just simple atmospheric oxidation over time, most paintings just can’t handle it and don’t. Thus, art restoration becomes a niche pursuit where damaged paintings can be restored to how they were intended without losing their value. But the process is not as simple as picking up a palette.

Old paintings have varnished layers. Varnish is a clear transparent finish that is used to preserve the pigment of a painting. It helps protect the color from degrading over time, but the varnish is also prone to oxidation, which turns a muddy brown to yellow. So, the first step after taking images of artwork is to clean the painting and remove the varnish. Here’s where the science begins. To remove the varnish, solvents are typically used to prevent damage to the paint layer. However, the incorrect solvent, the wrong concentration, or improper technique could irreversibly damage the paint layer. To make matters worse, not all 14th century varnishes are the same, and not all 14th century oil paints are the same. Thus begins an experimental approach of using different types of solvents on different varnish and paint combinations to determine the ideal course of action.

Left is Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinici painted around 1503 with its original varnish. In the middle is the Prado Mona Lisa before its restoration. Finally, on the right is the Prado Mona Lisa after it was restored revealing its hidden background.

The most common type of varnish used in the high renaissance was drying oils. Drying oils are oils that harden through creating internal stabilizing bonds. The formation of these bonds occurs only when water evaporates from the oil, giving them their name of drying oils. When the water evaporates, it allows for oxygen to catalyze internal reactions forming links between oil molecules. Thus, these drying oils form a clear yet firm external covering. Drying oils used to be a combination of linseed oil, polyurethanes, alkyds, and highly flammable organic solvents. Alkyds are polyesters that have been modified by the addition of fatty acids, thus, making them prone to aliphatic and lipophilic solvents. In the realm of art restoration, organic chemistry is king.

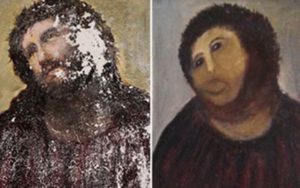

Once the old varnish is painstakingly removed, a new varnish layer is added. Then comes the controversial paint restoration. Art restoration, unlike art conservation, goes a step further in trying to recreate the artist’s original intent. In doing so, degraded regions of the painting are repainted. If the restorer is skilled, no value of the painting is lost, but sometimes, that’s not the case, as with a recent art restoration in Spain that had gone wrong. Art restoration is tricky and time consuming, but Julian makes it effortless and enjoyable. It requires trenchant attention to detail, patience, and a vast skill set including chemistry. Art restoration is not for the faint of heart, but the final product when done right are masterpieces.

Immaculate Conception by Bartolome Estban Murillo painted around 1678

Ecce Homo by Elias Garcia Martinez (aka “Monkey Christ”) painted around 1930

Peer edited By Brittney Shepherd and Fanting Kung

I like how you mentioned that a new varnish layer is added after the old one is removed and the original artist’s intent for the painting can be tried to be recreated. My wife is thinking of looking for a painting restoration specialist because she inherited some art from her parents and the piece was slightly damaged while it was stored away. It seems like a good idea for my wife to think about looking for a reputable professional that can help restore the artwork as best as possible so that it looks as original as can be.