As a young woman in pursuit of a career in academia, I find the underrepresentation of women in STEM careers, and specifically scientific research, to be a daunting statistic to face. In STEM fields, the percentage of tenure-line faculty positions held by women has merely increased from 19% in 2004 to 23% in 2012. In comparison, women composed 44% of non-STEM, academic positions in 2012. STEM fields are failing to matriculate women into faculty positions in equal numbers to men, and it is difficult to uncover the forces that create unfavorable and, at times, inhospitable environments for women in academia. Antiquated gender biases, intrinsically male-centric tenure track pressures, and deeply institutionalized chauvinistic attitudes do perpetuate inequality in academia, but what accounts for the discrepancy in STEM fields? Amid the institutional struggle to unravel the cryptic barriers impeding the advancement of women in STEM careers, I offer only my own struggle with gender bias and how it has shaped my career goals, and in turn what it means to me to be a woman in science.

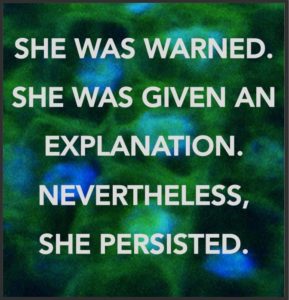

When I began my graduate program at The University of California, Riverside (UCR), an institution renowned for its diversity, I did not expect to encounter resistance based on my identity as a woman in science. During my first year of graduate level courses, a professor requested that I meet with her to discuss my future. I assumed she wanted to discuss my academic progress or perhaps inquire about my research topic of interest. Instead, she cautioned me that despite being an intelligent woman, I would need to change my personality to be respected as a scientist in academia, as I was too outwardly feminine. She impressed upon me that I would never be accepted by peers, be taken seriously by male faculty, or advance in the ranks of academia since it was still a “boys club.” Alternatively, she suggested that it could be in my best interest to refocus my career goals on positions at institutions with a higher emphasis on teaching rather than research. My perceived femininity would be a liability as I sought to climb the ranks of research institutions, and possessing effeminate qualities meant I was ill-equipped to undertake the rigors of a research career. Her message was equal parts pejorative and subliminal: I was the wrong kind of woman to be a researcher. In limiting my aspirations, she believed she was advising me. I was devastated; and yet, throughout my graduate work I struggled to escape echoes supporting her warning.

Three years into my doctoral research, I developed a body of evidence that won funding for an international research collaboration. During the first collaborative meeting, a foreign PI glibly remarked that the inclusion of women on research proposals was simply for appearances. He complimented my contribution, expressing more gratitude for my name than for my research, and he subsequently refused to share significant experimental responsibilities with women on the team. Not only was he disinterested in including women, he promoted the use of women as pawns to advance his own success, appealing to the image of gender equality without subscribing to it. My thoughts wandered back to the meeting with my past professor, and I wondered if she had possibly endured any similar experiences over her career? I imagined how discriminatory attitudes could have misshaped her own gender perceptions, misleading her to marginalize another woman’s potential under the veil of guidance, as perhaps she had limited herself.

I hope for a future where any semblance of gender bias is relegated to anecdotes of the past, but for now – though it is still very much a reality – I choose to persevere. The only thing that truly matters is that I am a woman who loves science. I will not become less feminine simply because it may be perceived as a weakness to some, and I have absolutely no intention to pursue an alternate career. I aspire to become a professor at a Research I institution, and my training at UNC will propel my development as an independent researcher to become a competitive professorial candidate. As such, I will be more than just a female STEM professor – I strive to become a woman with a superb record of research who serves as a positive and inclusive mentor, educator, and role model for my community and for other women striving to reach their greatest potential.

Peer edited by Salma Azam.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: