To me, it seems that the media hypes all new disease outbreaks as the advent of the apocalypse. More often, the facts about these epidemics are simply overstated or misrepresented. The Zika virus, also known as ZIKV, is the most recent epidemic in the news. Since early last year, there has been an outbreak of Zika fever in the Caribbean, Central, and South America, and the infection has spread rapidly since the first recorded cases in Brazil. Worryingly, reports are linking Zika to recent upsurges in birth defects and neurological conditions. Is Zika truly a virus to fear, or is this more media fear-mongering?

To me, it seems that the media hypes all new disease outbreaks as the advent of the apocalypse. More often, the facts about these epidemics are simply overstated or misrepresented. The Zika virus, also known as ZIKV, is the most recent epidemic in the news. Since early last year, there has been an outbreak of Zika fever in the Caribbean, Central, and South America, and the infection has spread rapidly since the first recorded cases in Brazil. Worryingly, reports are linking Zika to recent upsurges in birth defects and neurological conditions. Is Zika truly a virus to fear, or is this more media fear-mongering?

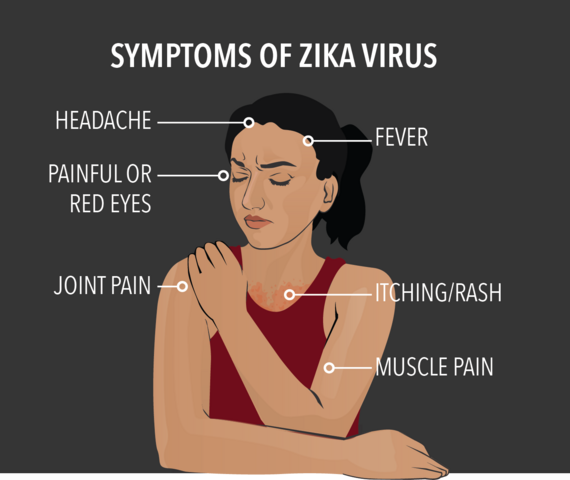

Zika is part of a family of viruses called flaviviruses, which includes members such as West Nile, Dengue, and yellow fever viruses. Flaviviruses are typically transmitted through bites from mosquitoes. The symptoms of infection are usually mild, and can include skin rashes, low fever, muscle and joint pain, or headache.

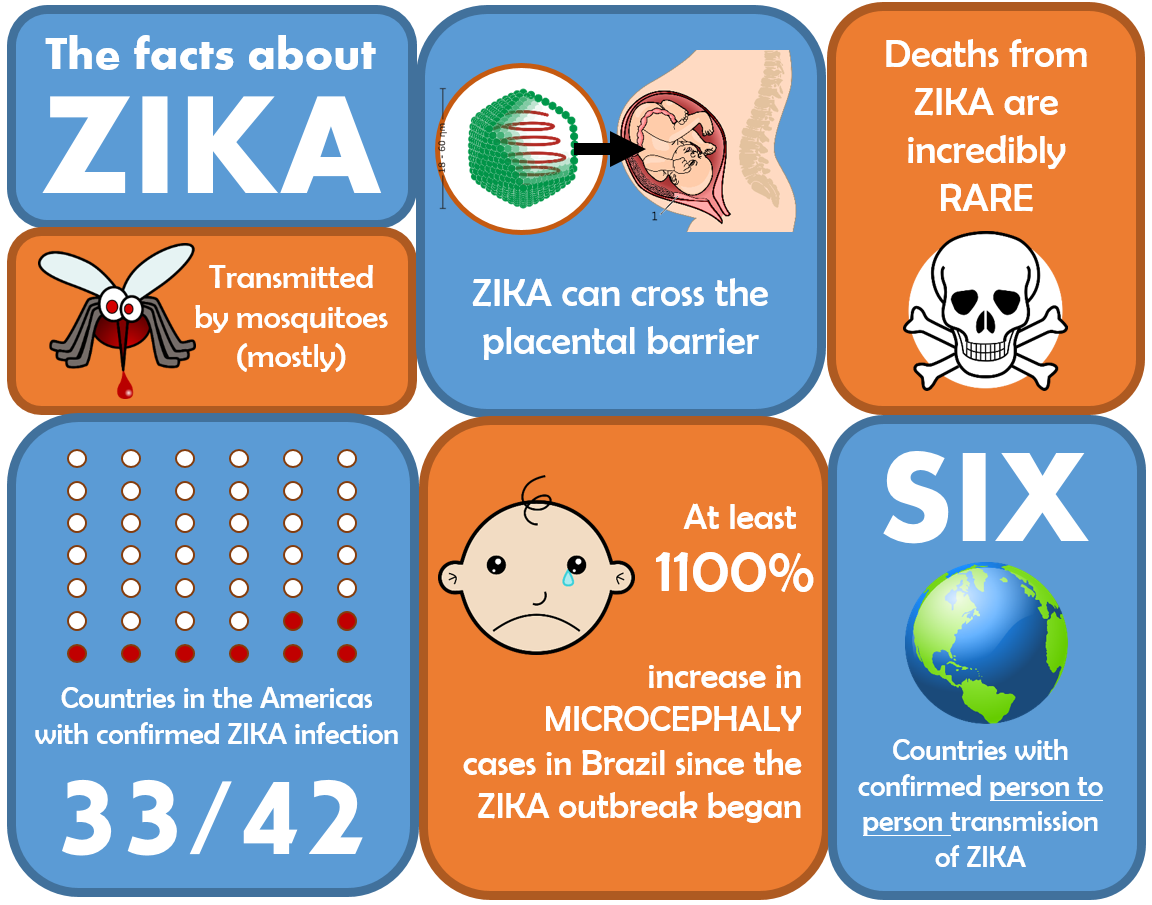

The Zika virus was first identified in 1947 in rhesus monkeys, and reports of Zika infections in humans began as early as 1952 in Uganda and Tanzania. Yet, there had been only 14 cases reported worldwide until recently; the first major outbreak began in 2007 on the Pacific Island of Yap. About 73% of residents were infected, and no deaths or hospitalizations were reported.

Although the symptoms of Zika infection are mild, there is growing concern that this illness may be more than what it seems. From 2013-2014, there were outbreaks of Zika in four other Pacific Islands. In these cases, we saw the first instances suggestive of a link between Zika and an ailment known as Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Guillain-Barré Syndrome is a very rare condition in which the immune system attacks nerves, causing muscle weakness and sometimes paralysis. It is thought that bacterial or viral infections can trigger Guillain-Barré Syndrome, and in fact, during the 2013-2014 Zika outbreak, there was a rise in cases of Guillain-Barré Syndrome, suggesting that these two events may be related. However, at the same time these islands were also experiencing an outbreak of Dengue fever, which complicates this link.

Yet another concern arose around the time of the first outbreak when evidence of sexual transmission of Zika virus was documented. A scientist from the United States contracted Zika in Senegal and later infected his wife upon return home. This is thought to be the first documentation of a mosquito-driven infection capable of sexual transmission, although it remains unproven. In the 2013-2014 outbreak, physicians detected Zika virus in the sperm of a patient seeking treatment for bloody sperm, which furthered suspicions of sexual transmission. To date, six countries have reported cases of person-to-person transmission of Zika virus including Argentina, Chile, France, Italy, New Zealand, and the United States.

In February of 2015, Brazil notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of an unknown illness characterized by a skin rash. From February to April, roughly 7000 cases were reported with no deaths. When blood samples were taken, about 13% of them tested positive for Dengue virus. By the end of April, the majority of these samples were confirmed to contain Zika virus, and by July Brazil had confirmed cases of Zika in at least twelve of its twenty-seven states. Astoundingly, a year since the first reports of Zika in Brazil, thirty-three of forty-two countries in the Americas have confirmed cases of Zika infection.

At the same time, concerns have been growing for an increase in cases of microcephaly in Brazil. Microcephaly is a rare birth defect in which a baby’s brain develops abnormally. As a result, the baby is often either born with a small head, or the head stops growing after birth. Babies with this condition can suffer from physical or learning disabilities, as well as convulsions. From the years 2001 to 2014, there was an average of 163 cases of microcephaly reported each year. However, in the last six months, there have been “a total of 6,671 cases of microcephaly and/or central nervous system malformations, including 198 deaths.” This most recent figure is somewhat misleading. Upon closer examination, WHO has investigated 2,378 of these cases and found that only 38% of the suspected cases are true cases of microcephaly. Although the rest of these suspected cases remain unconfirmed, it is clear from the cases that have already been confirmed that there has been an exceptional increase in the incidence of microcephaly. This phenomenon has currently only been reported in Brazil, but other countries are reporting increases in Guillain-Barré Syndrome.

So, is there a causal link between Zika and microcephaly? The short answer is that we don’t know. A recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine confirmed that Zika virus can indeed cross the barrier between mother and child known as the placenta. Relatively few diseases can cross this barrier, but because fetuses have little to no immune system function, these types of infections can be particularly dangerous. We also know that other viruses that can cross the placenta, like West Nile, can result in similar neurological birth defects.

While the exact prevalence of Zika virus in newborns and fetuses with microcephaly is unclear at this time, Zika virus has been repeatedly detected in fetal brain tissue. Additionally, in the fifteen Brazilian states with confirmed Zika virus infection, the incidence of microcephaly is 2.8 cases per 10,000 live births, whereas in the four states without confirmed Zika transmission, the incidence is 0.6 cases per 10,000 births.

WHO has declared both the Zika epidemic and the clustered increases in microcephaly to be a “public health emergency of international concern.” The United States has also issued travel warnings to pregnant women. However, the common co-incidence of Zika and Dengue virus creates problems for Zika research. These viruses are often transmitted simultaneously, making it difficult to separate the independent effects of each infection. To better understand the potential link between Zika virus and birth defects, researchers are currently monitoring cohorts of pregnant women with suspected and confirmed Zika infections. There is no known treatment for Zika infection, microcephaly, or Guillain-Barré Syndrome; however, there are ongoing efforts to develop vaccines against Zika virus.

Is this the end of the world as we know it? Definitely not. However, it is clear that the Zika epidemic may be more complicated than we thought.