Once hailed as a modern revolution, synthetic plastics allured many appreciable scientists like Nobel laureates Hermann Staudinger and Herman Mark. However, a century after the first synthetic plastic, Bakelite, was invented in New York by Leo Baekeland in 1907, we are witnessing its first-hand carnage manifest in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

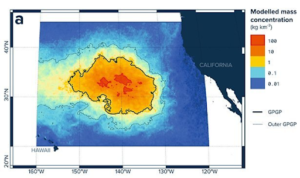

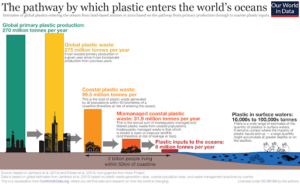

Contrary to popular belief, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a large system of circulating debris particles rather than a stationary plastic iceberg. However, it is a region thrice the size of France formed from 80,000 metric tons composed of primarily 1.8 trillion plastic pieces. The primary source of these plastics is improper waste disposal of manufacturing products. While the plastic debris is generated on land, it eventually finds its way into the ocean through various storm drains, rivers, harbors, cargo, and illegal deposition. According to the EPA, as of 2011 7 billion tons of plastic waste was produced in 1950 with only 21% either being recycled or incinerated. The other 5.5 billion tons remain in the ocean or on land.

Aside from clogging up our oceans, plastic pollution has ecological ramifications. Plastic pollution detrimentally affects over 800 marine species ranging from sea turtles to fish to dolphins. One melancholic example is that of the Laysan albatrosses. Of the Laysan albatrosses that inhabit the Midway Islands, 1.5 million of them will ingest plastic, and about a third of their chicks die from unknowingly consuming plastics from their parents. Of the twenty tons of plastic debris on the shores of Midway Islands, five tons will be fed to albatross chicks.

Plastics are often mistaken for food by marine life, as a result, plastics enter the food chain. It can eventually bioaccumulate and affect predators higher and higher up eventually leading to individuals in the form of microplastics. Preexisting microplastics in the ocean are also detrimental because they accumulate on the gills and intestines of marine life, interfering with their feeding and behavioral habits typically resulting in death. Furthermore, plasticizers in microplastics are known endocrine disruptors. Thus, exposure may result in abnormal growth and reproductive issues in many marine life. Organic pollutants like pesticides and toxic metals like lead and cadmium are also found in microplastics that may adversely affect their environment or the animals themselves when ingested.

The rampant plastic pollution of the earth’s oceans has adversely impacted marine ecology; however, some ecosystems have evolved to live with plastic environments called the Plastisphere. Some microorganisms in the plastisphere can degrade plastics. Thus, giving them a potential advantage in the barren wasteland and a potential exploit for scientists to harness.

Plastic was revolutionary at first, specifically in the war-torn era of the early to mid 20th century. It was a necessity. However, a century of overuse and mismanagement has led to the deaths of millions of marine life and the destruction of complete ecosystems. With the Great Pacific Garbage Patch still growing, it is evident that more policy and effort is still required to save the largest ecosystem in the world.

Peer Editors: Runfan Yang and Madigan Bedard