As a huge Minnesota Twins fan, I was sad to hear that former catcher and current first baseman Joe Mauer is still reporting concussion-related vision problems. These symptoms stem from three years ago, when multiple concussions led to his full-time conversion from behind the plate to first base. While problems with concussions are certainly more publicized in the NFL, they are also a concern in the MLB and other sports. Single concussions rarely have long-lasting, documented effects in athletes if they are allowed sufficient time to recover. However, repeated concussions seem to be a different story altogether. Despite having no recent reported concussions, Mauer is still struggling to return to the elite level of play that he displayed before his multiple head injuries in 2013. Similarly, former teammate Justin Morneau had a childhood history of concussions playing hockey, suffered a major concussion in 2010, and has since never fully recovered his form. Why do multiple concussions seem to play such an exaggerated effect on athletic performance?

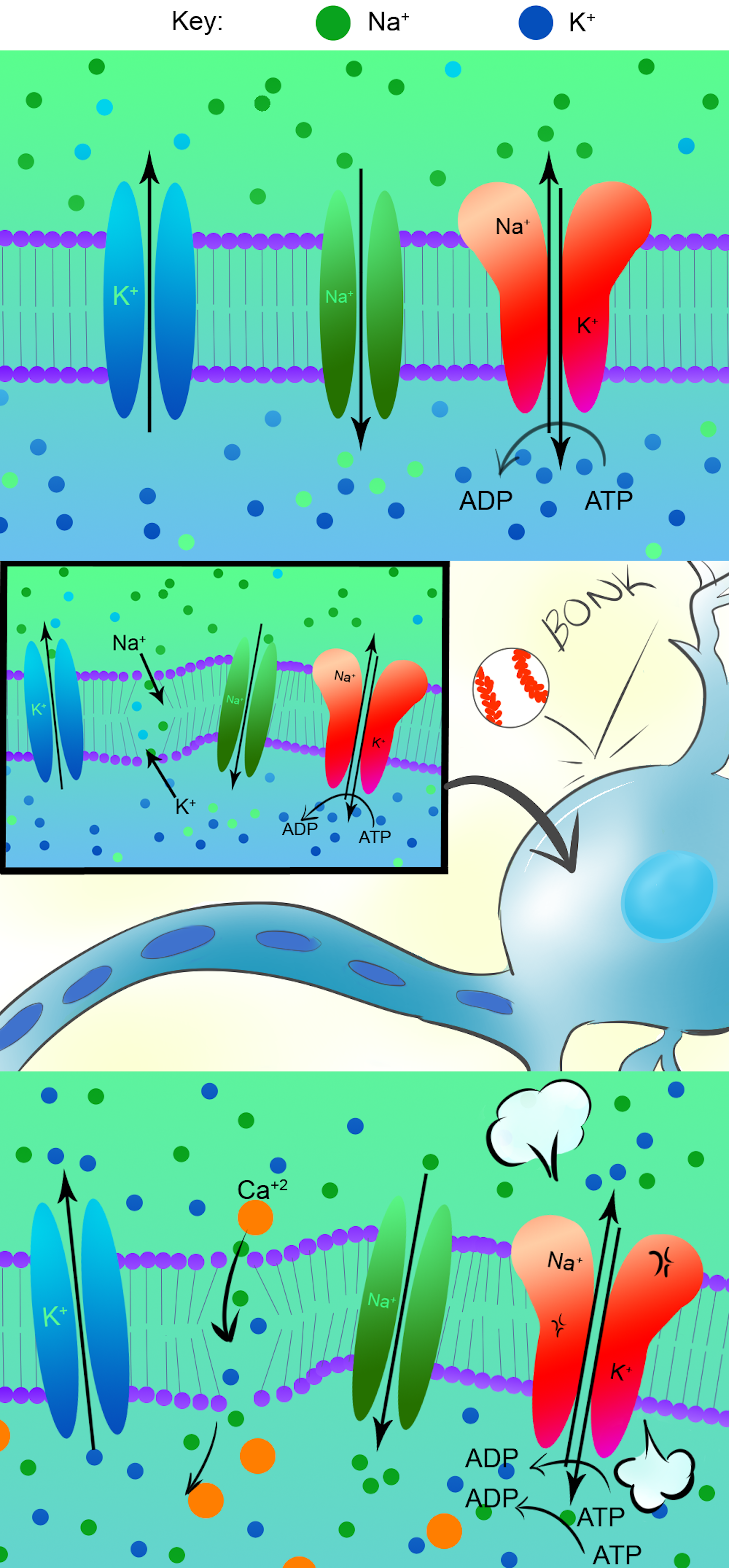

Before we can understand how repeated concussions affect the brain, it’s important to understand how the use of energy is controlled in healthy brain tissue. Despite composing only 2% of the body’s mass, the brain utilizes ~20% of its energy! This energy is typically provided by the consumption of glucose, which is carried to the brain via blood flow, a process that generates ATP (one of the main energy-providing molecules in the body). The largest portion of this energy goes towards maintaining the concentration of ions, or small charged particles, inside and outside of neurons. Maintaining a constant difference between inside and outside concentrations for each ion is crucial for regular brain activity. The key player is the sodium-potassium (Na+/K+) pump, which regulates ionic transport in and out of brain cells and has been shown to consume up to 2/3 of each neuron’s available energy. Ultimately, the brain is a tightly regulated, highly energy efficient organ.

Concussions impact this energy regulation process in many ways. Blunt trauma to the brain (say, caused by a foul tip of a speedy baseball into a catcher’s mask) can cause physical stretching and distortion of neurons. This allows ions to diffuse in and out of neurons without the aid of functional ion channels. In addition, excitatory neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, begin to be released at a higher rate, leading to even further accumulation of K+ ions outside of the neuron. In response, the Na+/K+ pump starts to frantically consume energy in an attempt to restore equilibrium. This energy is primarily provided via glucose. The rapid, exaggerated use of glucose causes a ‘cellular energy crisis’ in which sources of energy are dangerously low. During this state, neuron firing is suppressed throughout the brain, a phenomenon known as ‘spreading depression’. In addition, blood flow to the brain is reduced for a time following injury, preventing the restoration of ordinary energy consumption.

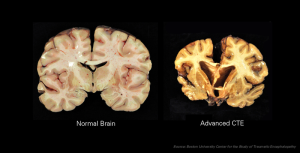

The brain can bounce back from this injury if it is given adequate time to recover, though recovery time can vary from days to months. However, a second brain injury that occurs during these ‘cellular energy crises’ can have dire consequences. Due to decreased brain blood flow (and thus lowered glucose transport), the brain cannot compensate for further expenses of energy. As a result, ionic concentrations are difficult to maintain and more dramatic damage can occur. In particular, excessive influx of calcium ions can cause defects in neuronal function and even trigger cell death! In fact, a progressive disease, referred to as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), has been discovered in individuals who undergo repeated brain trauma. Unfortunately, overt symptoms of CTE often do not emerge until years after the multiple concussions were suffered, making early detection difficult. Instead, definitive diagnosis of CTE is performed post-mortem. Interestingly, imaging studies in humans with CTE have revealed accumulation of the same toxic proteins seen in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. These proteins are thought to induce neuronal death, causing shrinking and distortion of brain tissue. Despite the increasing press that traumatic brain injury is receiving in the public and media, research on CTE is still in its infancy. As a result, no common treatment plan has yet been developed for CTE patients.

Because concussions are notoriously difficult to treat, the MLB has taken steps to diagnose and prevent concussions that may bode well for brain health amongst professional baseball players. Furthermore, several athletes are donating their brains to aid concussion research. Hopefully, increased awareness of the consequences of repetitive brain injury will cause cases like Mauer and Morneau to become distant, but poignant, memories.