Since the beginning of August, football stadiums have been bumping four days a week: Sunday, Monday, and Thursday for the National Football League (NFL) and Saturday for the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). While the allure and excitement of football is back, the return to the prime time spectating of crashing helmets means an inevitable increase in traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). TBIs, resulting from blows to the head, including both concussions and non concussive impacts, are the leading cause of death and disability in young adults. Recent years have shined light on the seriousness of repeated TBIs, which can lead to the development of a condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). This progressive and fatal brain disease is almost exclusively found in people with a history of repetitive head impacts. While CTE is not exclusive to athletes involved in high contact sports, as those in military service and first responders who have had repeated blows to the head may also be diagnosed, an overwhelming number of CTE cases are found in former and current collegiate and professional football players.

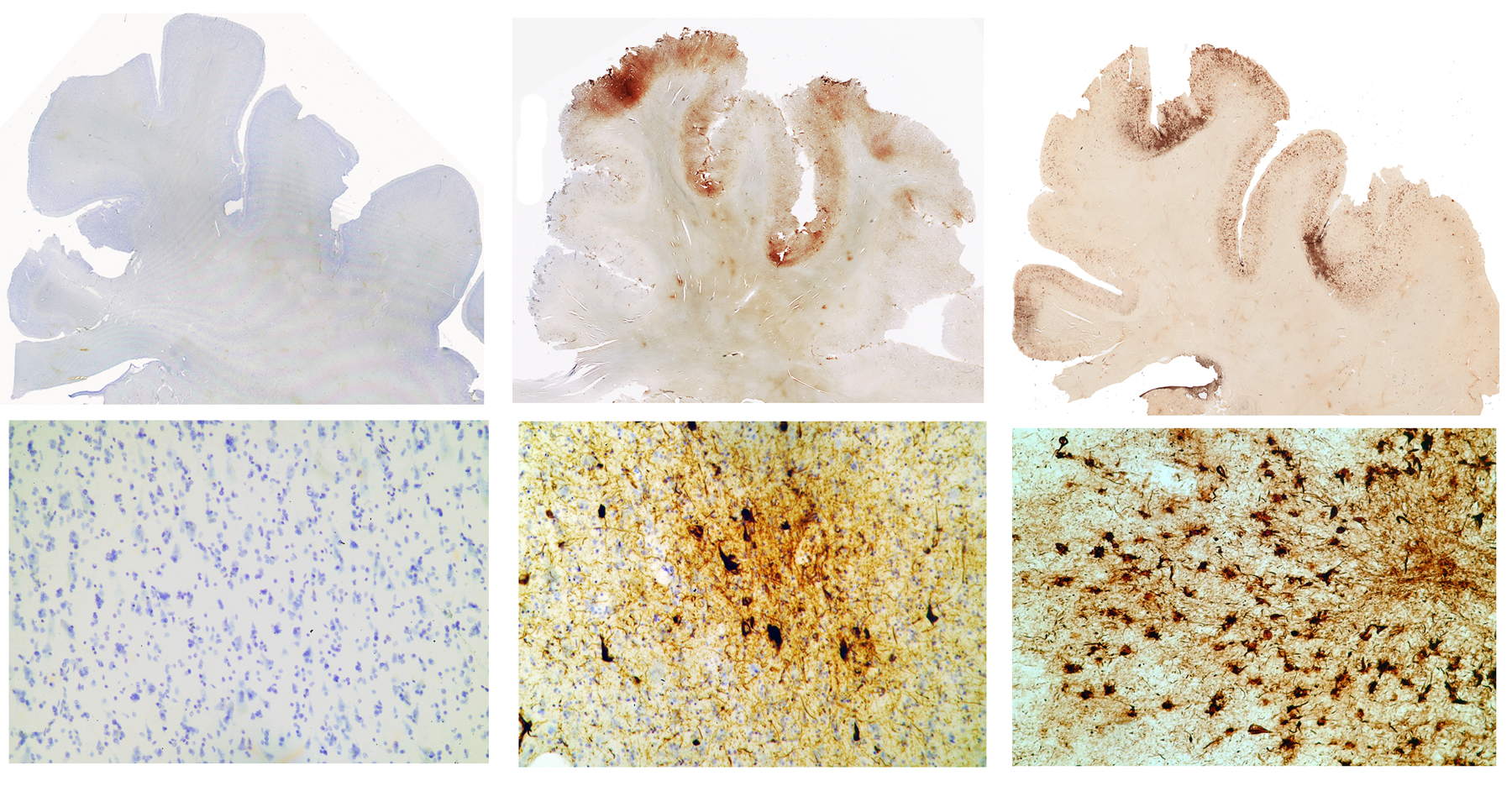

CTE results from buildup of Tau proteins in the brain, the same key protein involved in Alzheimer’s disease. Not surprisingly, CTE and Alzheimer’s share similarities with shrinkage in the hippocampus, memory difficulties, impaired judgment, behavior changes, and mood swings. Yet, the main difference between Alzheimers and CTE is age of onset; CTE symptoms generally present in one’s 40s while Alzhemiers symptoms present nearly 20 years later in one’s mid 60’s. Importantly, CTE does not arise after a handful of concussions. Rather, scientists believe CTE results from hundreds to thousands of head impacts over the course of many years.

Football is much more than just a contact sport

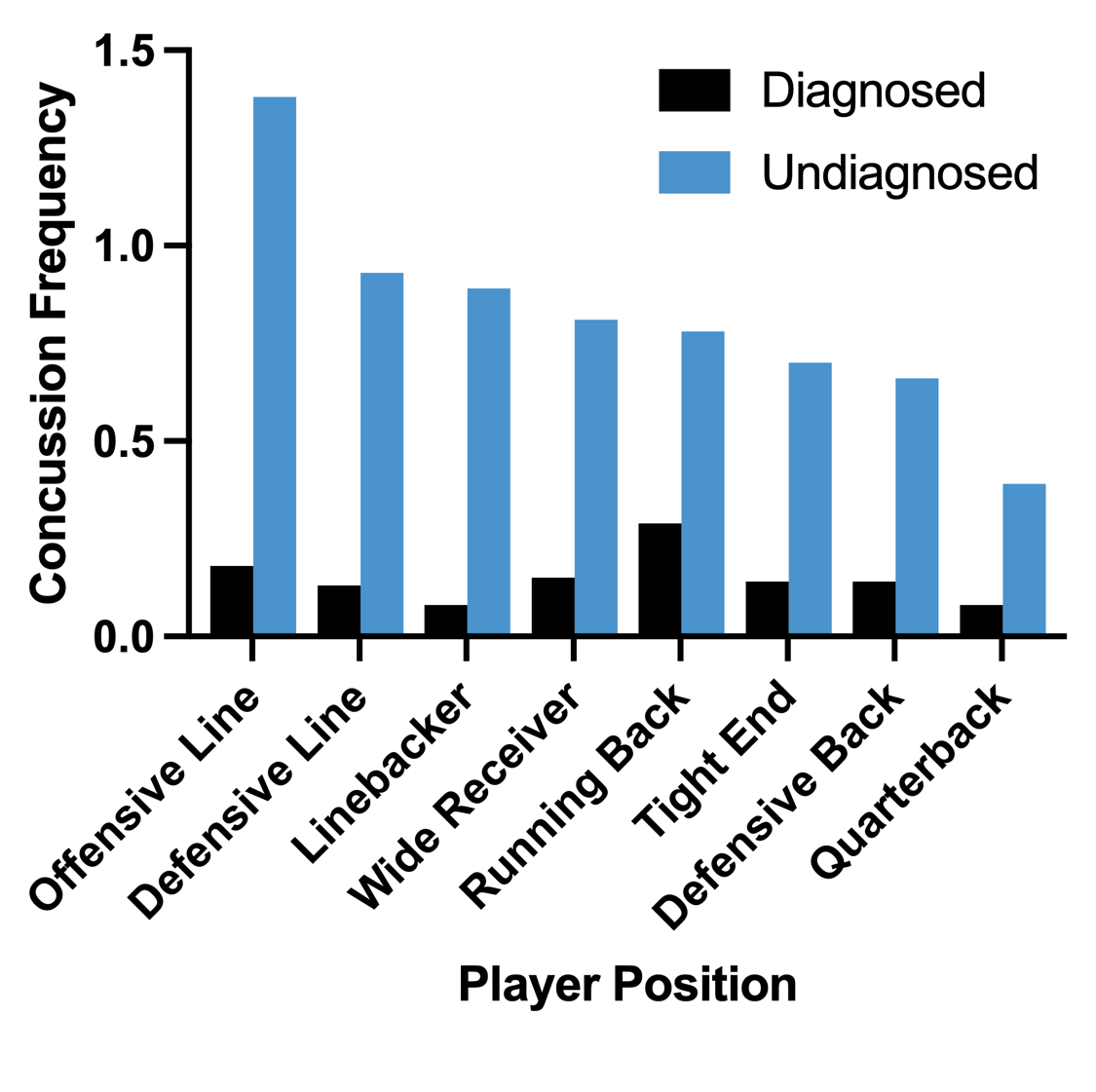

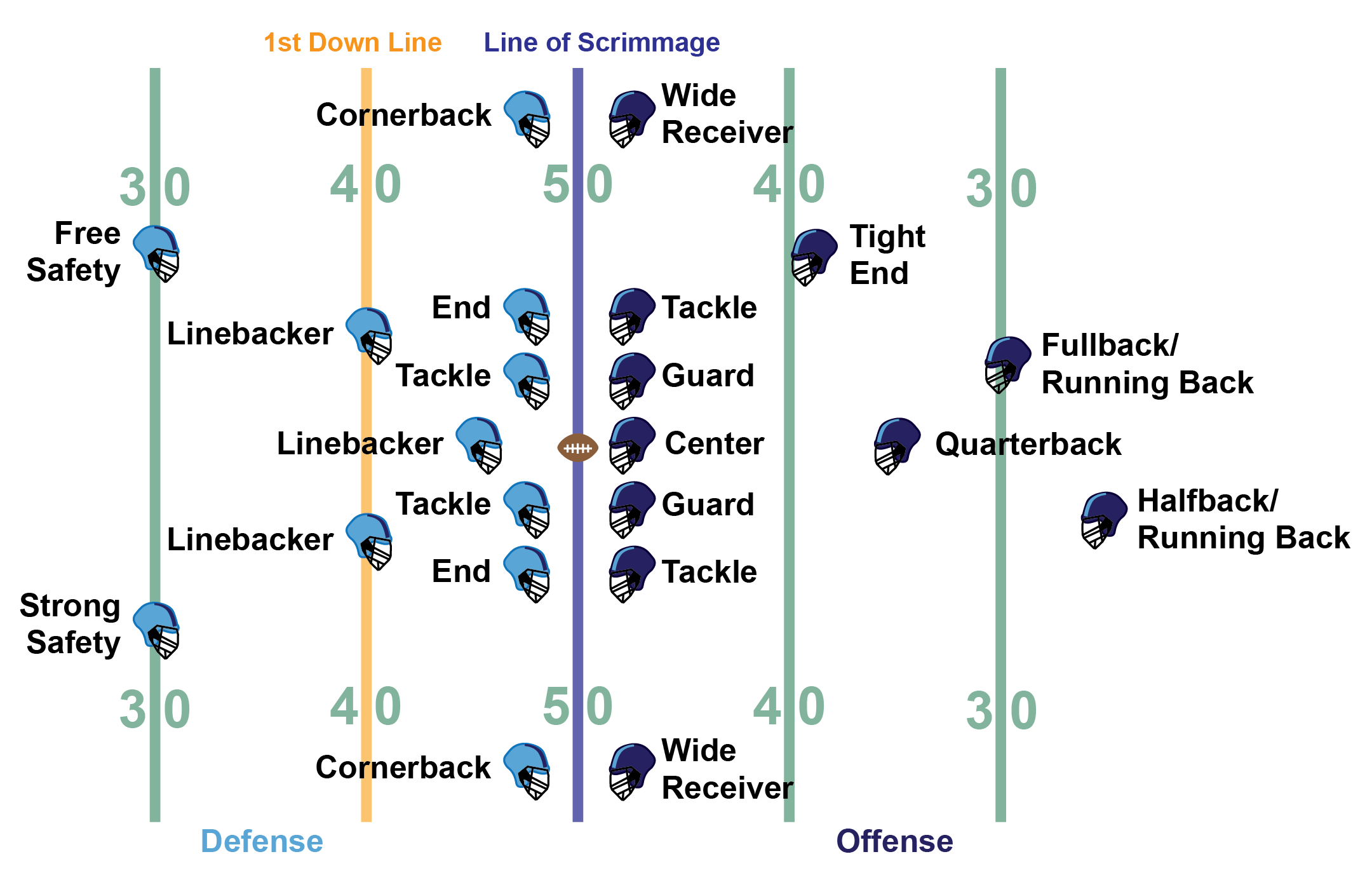

As Vince Lombardi, the legendary professional coach which the Lombardi Superbowl trophy is named after, accurately said “Football is not a contact sport; it’s a collision sport.” Each collision is a risk for physical and mental injury. Importantly, it’s not just concussions sustained during football play that cause brain damage. One study from Carnegie Mellon University and University of Rochester Medical Center found routine hits sustained from just one season of play caused structural changes to the brain. Football players receive over 1000 hits to the head per season. In one season, that’s an average of six hits per practice and 14 hits per game. Additionally, the odds of developing CTE correlate more with an increase in hits per play based on player position versus the degree of force in the hit. Players who take more hits, such as lineman and centers are at a greater risk of developing CTE. Notably, linemen and centers sustain more concussions per season than any other player, though the hardest hits are taken by wide receivers and running backs. When it comes down to it, football and TBIs go hand in hand. CTE is the grim reaper standing by.

In February of this year, the Boston University School of Medicine CTE Center, the leading center for CTE study and diagnosis in the country, announced they diagnosed 345 out of 376 former NFL players with CTE (91.7%). When looking at football specifically, the number of years played are associated with increased risk for CTE. Every additional year playing football is associated with a 15% increase of a CTE diagnosis. CTE is not just an NFL problem. As of 2018, at least one player out of 147 different collegiate programs has been diagnosed with CTE. Further, Boston University School of Medicine has published work demonstrating that out of 66 former collegiate players who never played professionally, 57 displayed evidence for CTE (86%). For perspective, Boston University has also evaluated 164 brains of men and women donated to the Framingham Heart Study, a longitudinal study on how aging impacts the heart and other organs. Of the 164 brains evaluated, only 1 showed signs of CTE. The lone CTE case belonged to a former college football player.

While the game has never been safer, it still doesn’t mean football is safe

There is no denying the causal link between head impacts and CTE. So far the NFL, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, United States Military, and National Institute of Health have all gone on record acknowledging the link between football and degenerative brain disorders such as CTE. By contrast, the NCAA has refused. Instead, the NCAA maintains “The risks of playing football are well-established.” When brought to trial over the death of a former USC football player, the NCAA questioned the science of CTE, moving to throw out every Boston University CTE study. The NCAA argues there is “no scientific consensus around the causes, symptoms, or definition of CTE.” Several NCAA football coaches argue the same, believing the game has never been safer. When questioned about the connection between football and CTE, former University of North Carolina Head Football Coach Larry Fedora said “I’m not sure that anything is proven that football, itself, causes (CTE).”

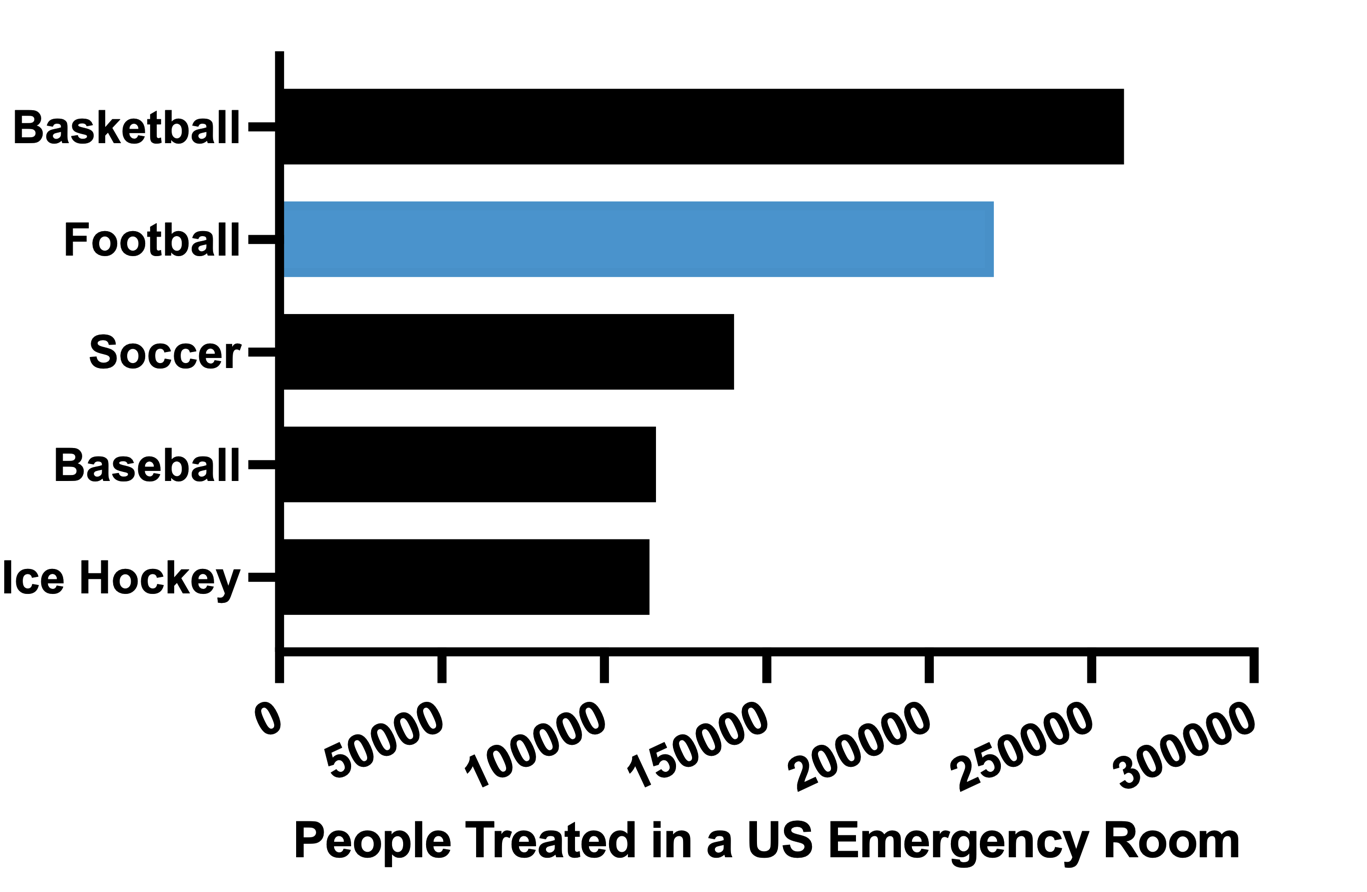

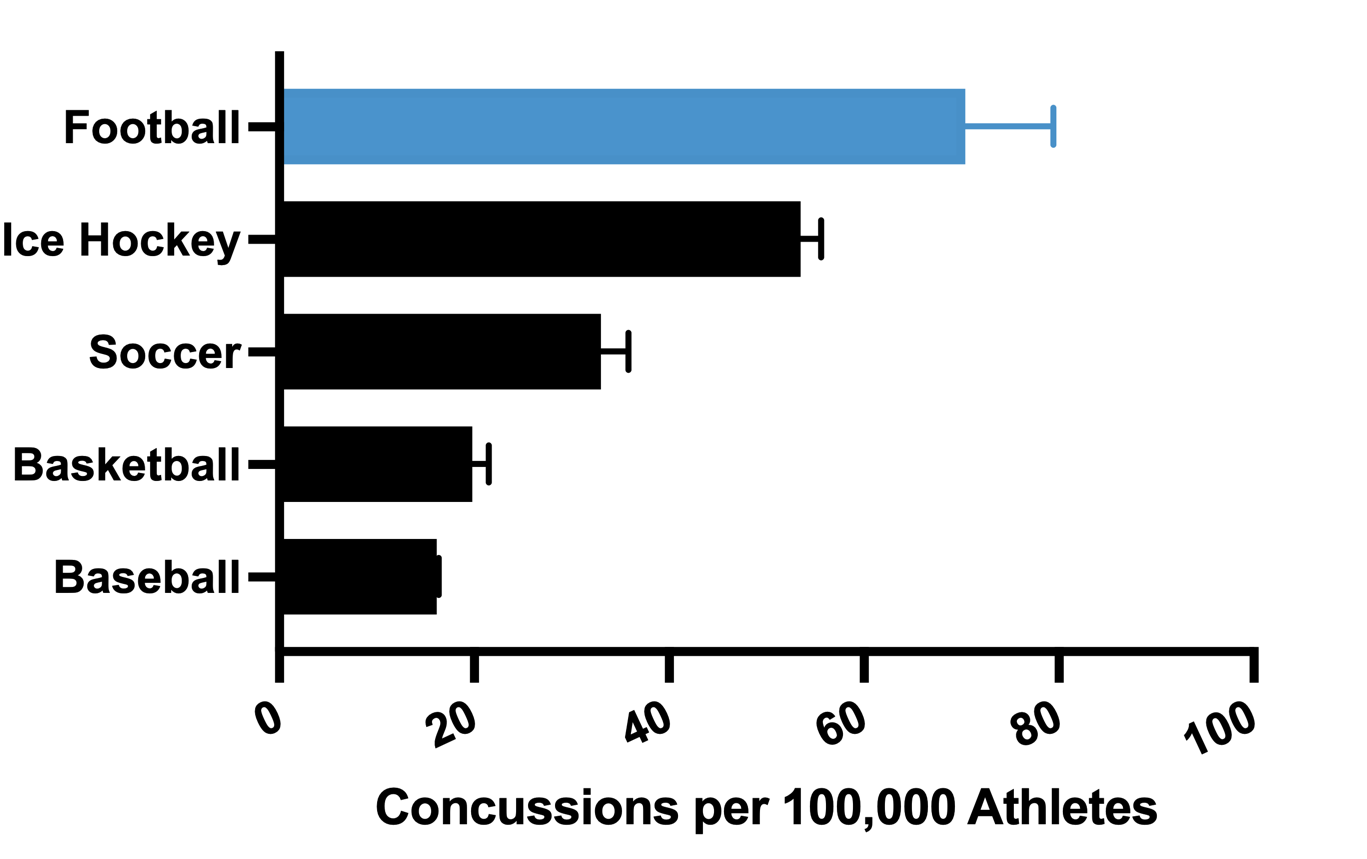

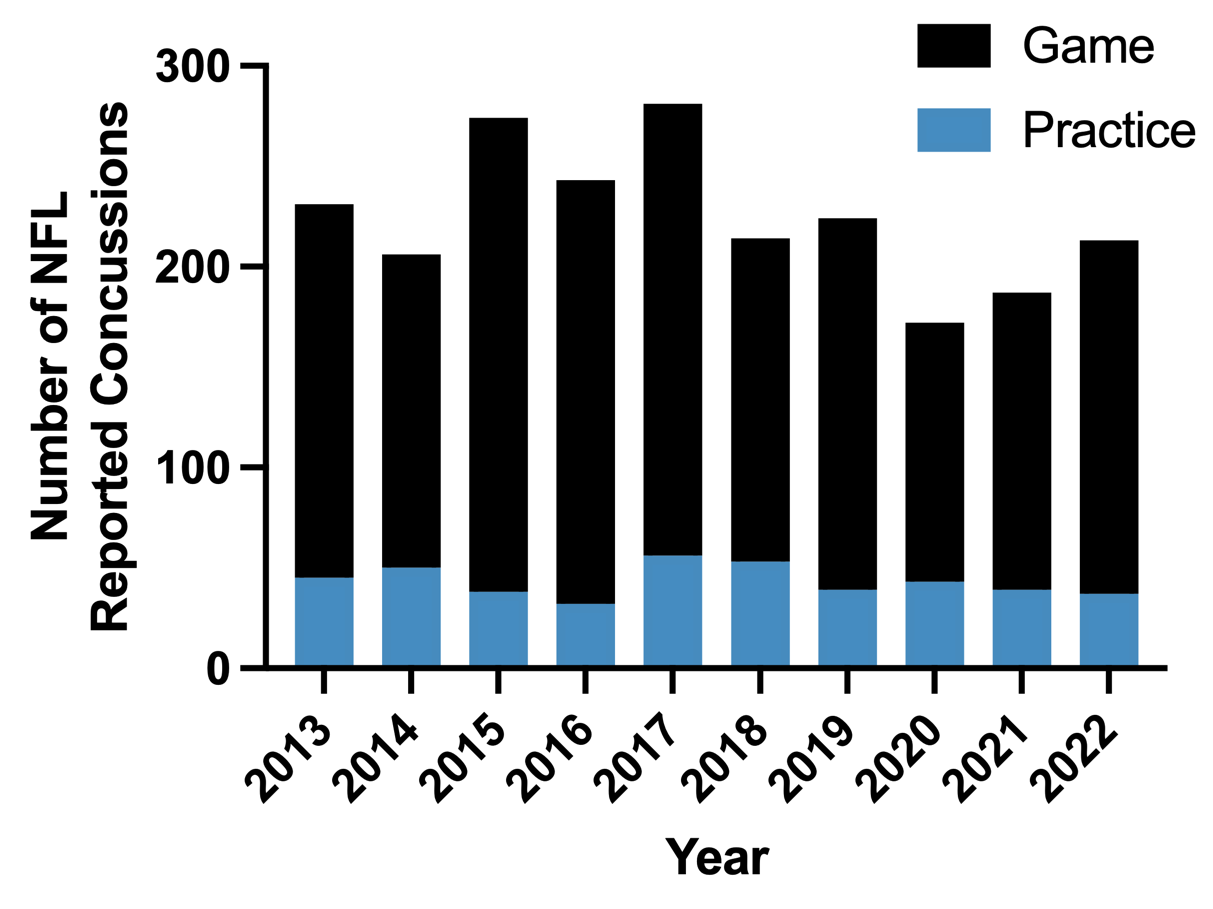

We certainly know playing football causes the most concussions out of any sport at any level of play (high school, collegiate, professional). Earlier this year, the NFL announced concussions rose significantly during the 2022 season with an 18% jump from 2021. Notably the NFL reports more concussions during competitive gameplay as opposed to practice. By contrast the NCAA reports that nearly 72% of diagnosed football concussions and 67% of all head impacts occur during practice.

Amid player safety concerns, Americans still love football

One of the very reasons Americans cherish and hold so tightly to football is due to the game’s unapologetic brute-force and omnipresent violence. This military style game of conquest and defense of territory has always been violent with one of the highest risk of injury out of any sport. When watching in person and on television we assume the players and coaches know the risks inherent to the game they are playing. Former President Barack Obama once stated professional football players “know what they’re buying into” in regards to the risk of concussions and brain damage. In the same interview in 2014 Obama also stated “I would not let my son play pro football.” In 2011 Jacksonville Jaguars Maurice Jones-Drew openly said, “Injuries are part of the game. If you don’t want to get hit, then you shouldn’t be playing.” However, recent data suggests players choose to play football long before they understand the full extent of the risks, namely the risk of chronic brain damage and CTE. A survey conducted by the NCAA revealed nearly 50% of football players underestimate their risk of injury when playing.

If love of the game and the quest for a championship ring truly outweighs the risk, why does a TBI strike so differently in the public eye than an ACL tear for example? Of any injury to sustain in athletics, brain injuries are more detrimental in the long run due to lasting, irreversible impacts that manifest in behavior changes that include: loss of attention, lack of concentration, language impairments, forgetfulness, aggressive tendencies, paranoia, depression, and visuospatial impairments (difficulty moving around). Several studies have shown correlations between head injuries and aggression, where a person with a higher number of TBIs is more likely to display aggression and irritability. If the average NFL player retires at age 27, and CTE symptoms begin onset in one’s mid 40s, what is the point of playing football if in 20 years a player can’t remember they even set foot on the field. Brain injuries are so intrinsically connected to a person’s mental well-being that watching someone progressively lose brain function is far more emotionally painful than watching an athlete experience an ACL tear. We may not know how CTE translates into symptoms, but we do, unequivocally, know repeated head impacts cause CTE.

While CTE is still being researched and there can be no formal diagnosis until an autopsy is performed post-mortem, it’s willful ignorance to deny the evidence linking high contact sports such as football and CTE.

Can football be made safer?

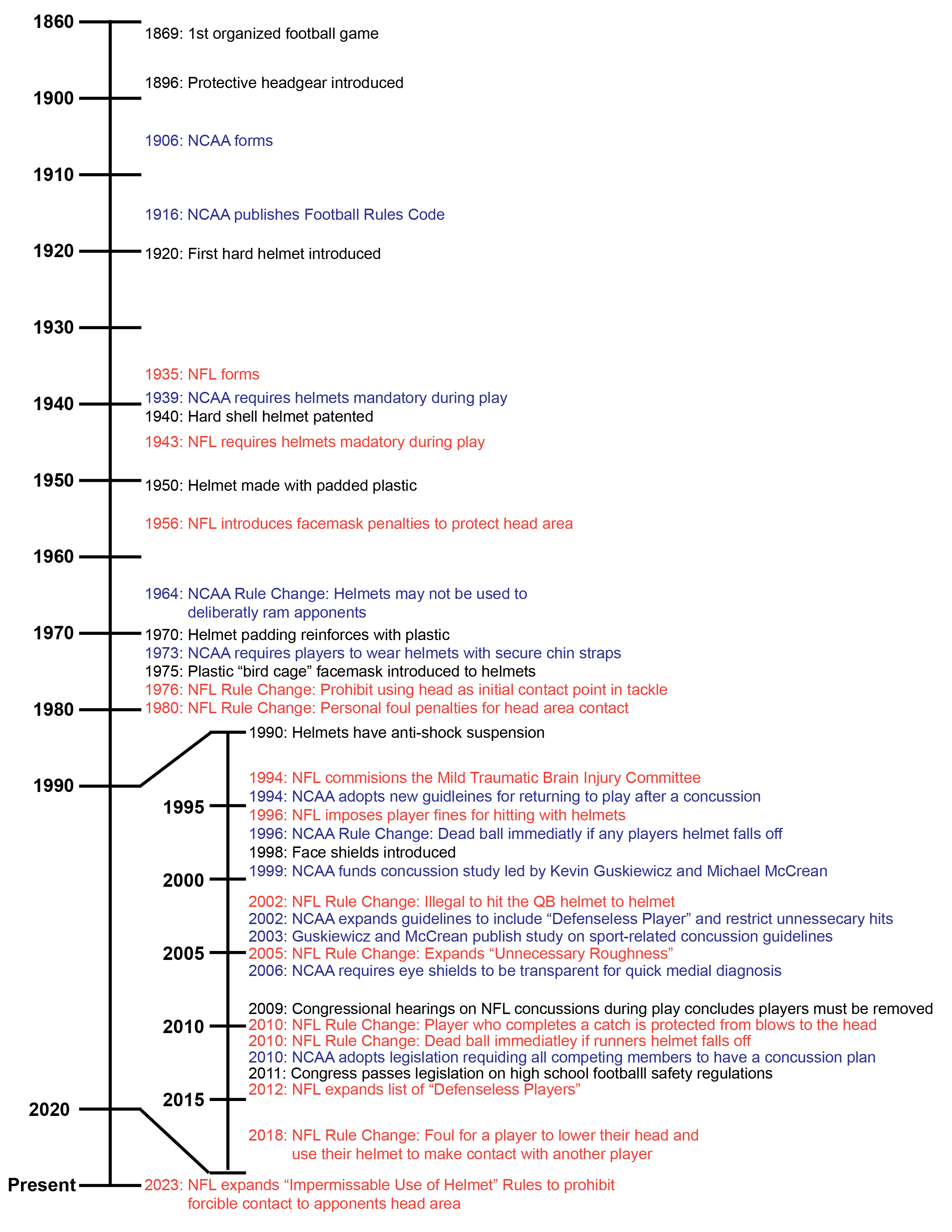

The NCAA’s own mission is to provide an athletic and academic experience to student athletes that “fosters lifelong well-being” and prioritizes “safe, fair and inclusive competition”. While the NCAA, as well as high school associations and the NFL, have gone to great lengths to increase the health and safety of players and improve helmet design for protection, there is only so much an enhanced helmet can do. A good helmet can protect against skull fractures and brain bleeds, but there is no helmet that can stop one’s brain from moving around in their skull. No helmet can prevent TBIs. No helmet can truly protect against CTE. It’s curious why the national governing body of collegiate sports designed to protect student athletes refuses to publicly acknowledge the link between high impact sports and CTE. Admitting the reality of TBIs from high impact sports, such as football and the development of CTE. could help accelerate prevention efforts and ultimately save lives. Admitting the connection between football, TBIs, and CTE is the first step towards meaningful regulation changes that can make football safer and protect the players millions of Americans tune in to watch weekly.

From multiple lawsuits pertaining to player safety to declining youth participation rates, there is no denying that the future of football is on shaky ground. Despite safety improvements in helmet design, concussions and TBIs will never leave the sport of football. As much as the NCAA may want it too, CTE is not going away. Both the NFL and NCAA have major decisions to make in regard to the future of this beloved American sport. Given that life altering injuries are built into the way football is played, then perhaps it’s time to change the rules of the game. Reducing the number of full-contact hits during practice, ditching the kickoff (which accounts for 21% of all concussions), and encouraging officials to more stringently call targeting penalties are all ways that TBIs can be reduced. Some have made the case that banning helmets may make football safer as it will remove the invulnerability players feel on the field. Without a serious adjustment to how football is played, CTE will remain an alarmingly common occurrence in America’s favorite sport.

Peer editor: Maria Cardenas