If a urinary tract infection (UTI) has ever ruined your day, you’re not alone. This uncomfortable condition is one of the most common infectious illnesses in the United States, responsible for more than ten million office visits and nearly $4 billion in costs each year. UTIs are usually diagnosed based on the results of three different types of test:

1. Dipstick test: a prepared test strip provides basic information about the urine, including things like pH and the presence of blood cells or nitrites (a byproduct of some bacterial infections). The dipstick is fast and inexpensive but not very sensitive, leading to both false negative and false positive results.

2. Microscopy: examining urine under a microscope to check for the presence of red and white blood cells or bacteria directly. This is a relatively quick and inexpensive test but is also prone to false negatives and false positives.

3. Urine culture: currently the gold standard of UTI diagnosis. For this test, a sample of urine is plated on materials that will allow bacteria to thrive and then it is observed for 48 hours to see if any bacterial colonies will grow. Culturing urine samples allows the lab to identify the species of bacteria responsible for an infection and test antibiotics to determine the best treatment. Growing cells in culture can be difficult, however, particularly if bacteria live together cooperatively in a growth called a biofilm which is common in the urinary tract. This makes false negative results a problem for urine culture.

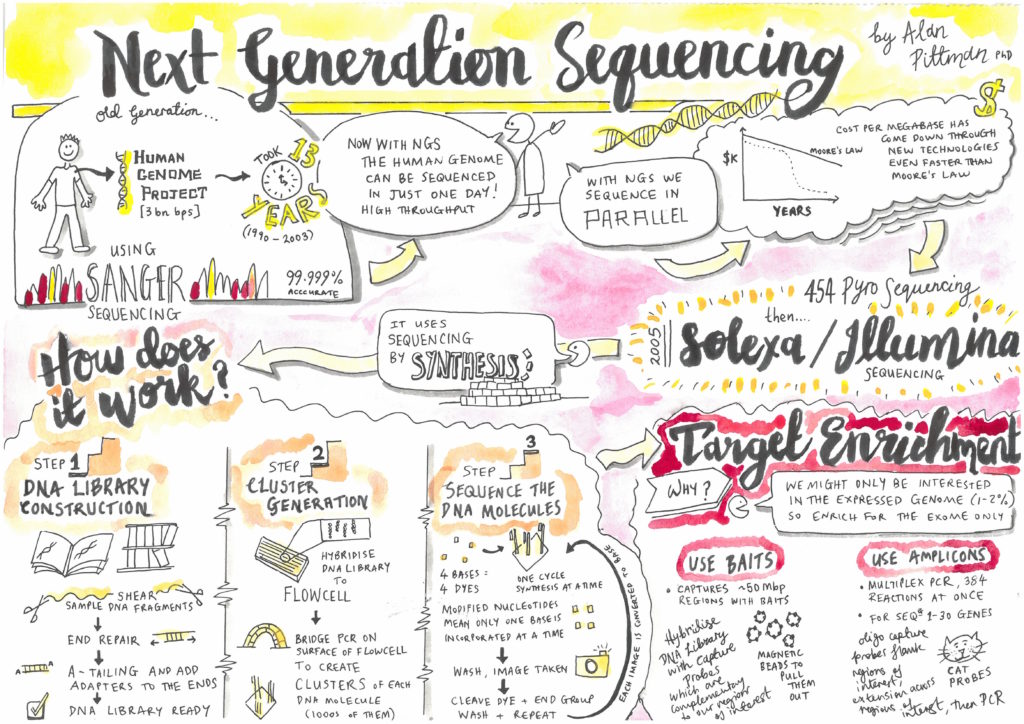

Recently, new technology has been introduced into UTI diagnosis that may eventually change the way in which infections are identified. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) allows the lab to test urine samples for several bacterial genes to identify infections without the need to grow bacteria directly in culture. PCR is more sensitive than urinary culture and may be able to provide evidence of bacteria that are more difficult to identify by culture, like biofilm infections. More sensitive still is next-generation sequencing (NGS).In this technique, rather than testing for a few specific bacterial genes that may be present in the urine sample, the lab can identify every single bit of genetic material in the urine. This allows the lab to identify every organism that is living in the urinary tract, and test for the presence of genes that confer antibiotic resistance to suggest a more targeted antibiotic therapy. These methods are poised to make UTI diagnosis and treatment more precise and less prone to false negatives.

However, these more sensitive tests do have limitations. By identifying many more species of bacteria than urine culture, NGS may detect species that are present in urine but not responsible for urinary symptoms. In a comparison of NGS and urine culture, although NGS and culture identified the same bacteria in UTI patients 96% of the time, NGS also identified many species of bacteria in healthy control participants. Why were these healthy patients testing positive for bacteria? Although historically the urinary tract has been described as a sterile environment, modern evidence suggests that the urinary tract has its own microbiome, where multiple species of microbes live without causing human illness. This research is still in its infancy, and until the microbiome of the bladder has been thoroughly described it will be difficult for doctors to determine whether a species identified via NGS is an infectious organism or a normal part of the patient’s urinary tract. Another disadvantage is cost: these new tests are also much more expensive and not often covered by insurance, and not all doctors are willing to use the results to make treatment decisions.

So, are these new tests worth it? That’s a question only the patient and their doctor can answer. For now, these more sophisticated techniques are best used as a companion to traditional urinary culture, not a replacement, until clinical standards are established. It might be helpful to think of NGS as similar to “23andMe for your bladder”- the information is interesting, and some of it might be useful for your medical provider, but for now it’s mostly medical trivia. Here’s a summary of the test options:

| TEST | SPEED | COST | DRUG TESTING | FALSE NEGATIVES | FALSE POSITIVES |

| Dipstick | Instant | $ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Microscopy | Instant | $ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Culture | 2 days | $$ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncommon |

| PCR | 1 day | $$$ | – | Uncommon | Uncommon |

| NGS | 4 days | $$$$ | ✓ | Uncommon | ✓ |

Peer-edited by Kathryn Weatherford and Chiung-Wei Huang.