It was a fateful day in McNally Jackson Independent Booksellers, nestled in the Nolita neighborhood of Manhattan, that I deviated from my Sci Fi & Fantasy comfort zone and meandered into the section of Architecture and Design. For amongst the objectively cool, but exceedingly niche offerings of architecture in Yugoslavia from 1948-1980, or a deep dive into the engineering feats of bridges, stood a book titled The Great Indoors: The Surprising Science of How Buildings Shape our Behavior, Health and Happiness.” I had never realized there was a scientific field studying the impacts of architectural design on health, but, as a human who spends a great deal of time indoors, I was immediately curious to learn what it was all about. The book came home with me.

The novel, written by science journalist Emily Anthes, takes the reader through several building types—such as schools, hospitals, and prisons—and describes how their design impacts inhabitants, from academic performance of students in schools, to patient outcomes in hospitals, to mental and physical traumas in prisons. Anthes references several specific buildings from across the world to illustrate specifically how their constructions affect human health and behavior. It was a fascinating read, and I found the chapter on hospitals particularly interesting as it concretely linked (pun intended) good and/or bad design with health and disease.

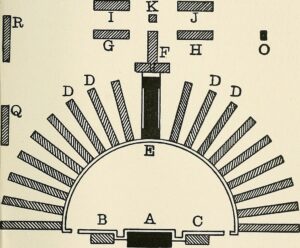

The chapter begins with a summary of the evolution of the contemporary hospital. Anthes describes how, in the early 1800s, hospitals were unsightly, underfunded, and largely catered to the poor. They lacked good hygiene and patients were often crowded together, creating the perfect conditions for infectious diseases to thrive. It wasn’t until Florence Nightingale (Figure 1), the founder of modern nursing, intuited in the mid-1800s that medical care should be provided in clean, well-ventilated areas with loads of natural light and patients spread out as much as possible, that hospital mortality rates dropped. This all may seem obvious now, but these notions were revolutionary for their time, especially since modern germ theory had yet not been established. In fact, these principles propelled the emergence of “pavilion-style” hospitals in the latter half of the 19th century, where long patient corridors extended from a single, central core, like branches from a tree trunk (Figure 2). Each patient room had windows to the outdoors and received plenty of fresh air and sunshine.

However, with the conception and popularization of germ theory, the pavilion style gave way to more sterile environments, distinctly devoid of nature. Rooms became isolated in an effort to protect them from microbes, and chemicals were used to disinfect instead of sunshine and fresh air. Despite their bluntly cold, dismal and “emotionally unsupportive” dispositions, Anthes writes, this new style of hospital persisted as the dominant design up through the 1980s. In part, this was due to a lack of rigorous assessments to measure how well a given design worked. Without this accountability, architects had no pressure to ensure their concepts would benefit patients and healthcare professionals. As a result, hospitals were often designed for efficiency, not unlike factories.

The game changed when Roger Ulrich–now a professor of architecture at the Center for Healthcare Building Research at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, then a fresh PhD graduate studying the effects of nature on mood and emotion–sought to study nature’s impact on a population of highly stressed individuals: hospital patients. To conduct his study, Ulrich found a hospital in Pennsylvania where one wing had a view of a cluster of trees while another wing overlooked a brick wall. He then analyzed medical records from 46 gallbladder removal patients and observed that patients in rooms with the scenic view needed fewer doses of narcotic pain relievers and on average spent a day less in the hospital. His discovery, published in Science in 1984, marked the birth of “evidence-based design”, where constructions are based on scientific research.

Nature’s healing effect was solidified through dozens of following studies. According to Anthes, humans aren’t picky when it comes to enjoying nature. All forms—even images and sounds of nature—lead to reduced anxiety and pain, lower blood pressure, and even boosted immune systems.

In addition to creating lush courtyards, meditations gardens, and hanging serene nature paintings in patient rooms, hospitals can incorporate other design features to improve health outcomes. For example, some hospitals are taking steps to better sleep quality. One approach is to use “circadian lighting”—where bright, blue-toned lights used in the morning are gradually transitioned to warm, dim lighting at night to prime the body for sleep. Another strategy is to tackle the noise problem—as it turns out, with constant mechanical humming, beeping alarms, and general hustle and bustle ad nauseam, “hospitals can be as noisy as highways and are often considerably louder than the World Health Organization recommends”, Anthes writes. One potential fix lies in the installation of sound-absorbing tiles, as was done in a coronary ICU in Huddinge University Hospital in Sweden. After installation, patients appeared to sleep better, display less signs of stress, and were less likely to be readmitted in the 3 months following their stay.

If one is looking for a poster child of evidence-based healthcare design, they can look no further than Dublin Methodist Hospital in a suburb of Columbus, Ohio. The hospital, which opened in 2008, incorporates many of the measures shown to improve patient outcomes to date. Nature imagery lines the walls, large windows to the outdoors are present in all patient rooms and public spaces, and a three and a half-story waterfall flows in the main lobby. Additionally, all patient rooms are acuity-adaptable, meaning they are equipped with technology to support the medical equipment a patient needs as they heal. This means that patients can stay in the same room throughout their visit, decreasing their stress and reducing the likelihood of medical errors that might arise from a location switch. Patient rooms are private, sound-absorbing tiles line the walls, and common atriums and gardens are available to all. While long-term analyses studying the effects of these features on patient outcomes still need to be done, patient satisfaction was >90% in the first few years, while medical mistakes and hospital acquired infections remained scarce.

Through these examples, Anthes has shown how architecture and design definitively impact human health. There is of course still much to discern and improve, especially when considering how design can impact those that provide healthcare services. It is certain, however, that hospital design can affect patient stress, pain, sleep, mood, and recovery speed—making it clear that, in itself, “good design is powerful medicine.”

Peer Edited by Taylor Tibbs