How much you eat (or don’t eat) can affect how well your cancer treatment works. Researchers have recently discovered that a fasting diet in mice can improve response to treatment. It can also reduce negative side effects often caused by treatment. In their study, they examined the effect of fasting in combination with immunotherapy to treat tumors and also its impact on changing the immune environment of the tumor in breast cancer models.

Immunotherapy is a treatment that engages the immune system to fight off the disease rather than killing the cancer cells outright. A type of immunotherapy called checkpoint inhibitors release the brakes of the immune system to allow the body’s immune cells to recognize the cancer cells. They have been FDA-approved for many types of cancer. However, many patients do not respond to checkpoint inhibitors, though patients with some types of cancer respond better than others. While on the therapy, patients often suffer serious immune-related adverse events, sometimes culminating in autoimmunity. Increasing the number of patients that respond well to checkpoint inhibitors as well as decreasing the treatment side effects remain two hallmarks of research today.

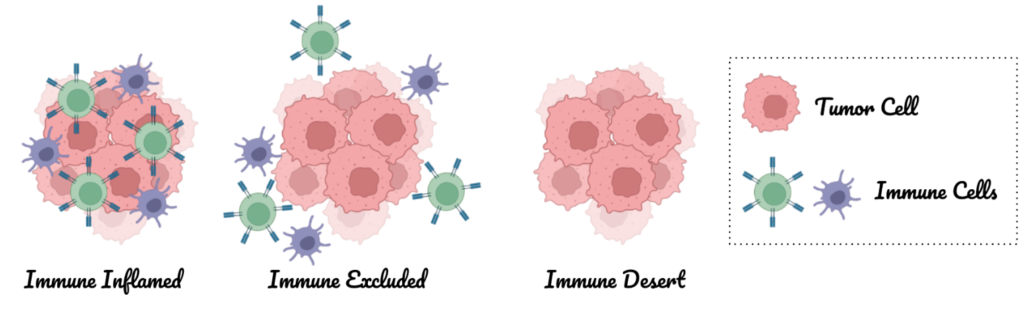

A patient’s responsiveness to immunotherapy depends on a number of factors, some of which are the composition, type, and function of immune cells and signals in the tumor. Typically, the immune environments are classified as inflamed (a plethora of immune cells are present but are “turned off” and either cannot kill the cancer cells or promote tumor growth), excluded (immune cells are on the borders of the tumors but cannot infiltrate the tumor), or desert (immune cells are nowhere to be seen near the tumor).

Cancer immunotherapy seeks to (1) bring immune cells into the tumor if they are not already present (make the tumor immune inflamed) and (2) reverse the environment that is suppressing the immune system within the tumor. It can accomplish these goals by increasing the number of anti-tumor immune cells and decreasing the number of pro-tumor immune cells (they help or allow the tumor to grow).

So if fasting improved checkpoint inhibitor effectiveness compared to not fasting, how did fasting change the immune environment in the tumor? The immunotherapy and fasting combination resulted in more anti-tumor immune cells that could crawl into and attack the tumor. Additionally, the combination altered the pro-tumor immune cells, leading to less suppression of the immune system. Furthermore, it also changed the actual physical structure of the tumor by reducing the amount of collagen that accumulated in the tumor. Collagen has been correlated with tumor growth and poor prognosis, so less is better.

What did they find? Fasting improved the response to therapy, lessened the adverse events, and changed the immune cell population in mouse models of breast cancer. When mice which were on a fasting diet were given immunotherapy, their tumors grew more slowly than those of mice which were receiving the therapy on a regular diet. Additionally, fasting helped reduce negative side effects, including the risk of anaphylaxis often associated with checkpoint inhibitor therapy. In order to see these effects, mice needed a working immune system, otherwise the fasting and immunotherapy combination would not affect the growth of the tumor.

(image created with Canva)

Mice are not humans, but the promise of these results suggests that some patients may benefit from fasting while being treated with immunotherapy. Clinical trials will be needed to confirm this hypothesis as we work to improve treatment for human cancer patients.

Peer Editor: Caitlyn Molloy

Nice!