Breaking news was announced to the world in February regarding the HIV status of a female patient. Due to an innovative treatment, the formerly HIV-positive patient has been HIV-free for 14 months and effectively declared “cured.” Before we discuss what the treatment was and what this means for patients with HIV, I want to provide some background on the disease and status of current treatments in case readers are unfamiliar with them.

What is HIV?

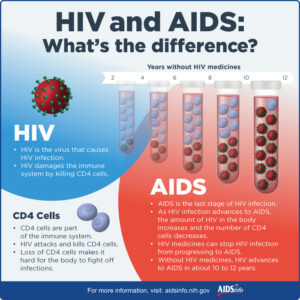

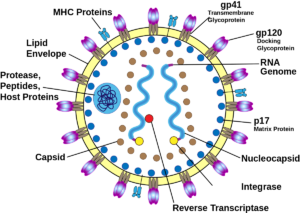

As of 2019, approximately 1.2 million Americans live with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infections, and 37.7 million people were infected with HIV globally in 2020. HIV is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system by infecting and killing CD4 T cells, which are also called helper T cells. HIV infects CD4 cells for replicative purposes as it will not replicate nor survive outside of its human host. By infecting the CD4 cells, the virus co-opts the cell’s machinery to make the cell a virus-production factory. The cell fills with copies of the virus and then bursts, which kills the cell while also spewing out newly made virus. Another way HIV infection can lead to CD4 death is by infecting the cell, which can trigger a cellular response called apoptosis. Apoptosis is a cell self-destruction program.

CD4 cells are an important part of the immune system and play a vital role in combating infection. Since HIV infection destroys a person’s CD4 cells, their ability to fight infection can be affected. If untreated, HIV infection can lead to AIDS, which is a chronic condition that can be life threatening. AIDS patients have so few CD4 cells that they are immunocompromised. This makes them susceptible to other illnesses, called opportunistic infections, and even cancer.

How is HIV transmitted and can its transmission be prevented?

The most common ways HIV is transmitted are through sexual contact and sharing needles. HIV can also be transmitted between mother and child during pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding. These exposure routes are called “perinatal transmission” but are much less common due to advances in treatment and preventative care.

Bodily fluids that can transmit HIV include blood, semen, and breast milk. Saliva, tears and sweat will not transmit HIV. HIV is also not transmitted through the air, public toilets, mosquitos, or ticks, nor by hugging, shaking hands, or sharing food and drinks.

There are preventative measures such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to reduce HIV transmission. There are two FDA-approved PrEP medications, and these drugs are taken to prevent getting HIV from sex or from needle injection use. When taken as prescribed, PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV significantly. PEP can prevent HIV infection, but must be taken within 72 hours of exposure.

How is HIV diagnosed?

HIV is diagnosed using blood tests to check for (1) HIV nucleic acid, (2) HIV antigens and antibodies, and (3) HIV antibodies alone. A nucleic acid test will use blood from a patient to determine if and how much HIV virus is present. The amount of HIV present in the blood is known as HIV viral load. The viral load is a metric that can be used to first diagnose and second monitor the patient’s response to treatment. The other main test type is the antigen/antibody test that will check for the presence of HIV antigens and antibodies to determine HIV infection status and can do so within 2-6 weeks of infection. When a person is exposed to a pathogen, such as HIV, the body will mount an immune response with antibodies against that antigen to attempt to clear the pathogen. HIV produces an antigen called p24. This p24 protein is specific to HIV and will not be found in uninfected individuals. The antibodies the body produces against HIV are specific to the virus. The last test will only look for HIV antibodies present in blood. It can also be done with saliva but keep in mind that antibodies against HIV can be present in saliva even when the virus is not. This test can determine HIV presence 3-12 weeks after infection and is the only type of HIV self-test available.

A confirmed case of HIV will be classified using the 3 stages. The first stage is acute infection, when an infected individual is highly contagious and many experience flu-like symptoms. The second stage is considered chronic infection. In this stage, the HIV is still active and contagious but is reproducing at low levels. Treating HIV in Stage 2 can prevent the disease from progressing to Stage 3, which is AIDS. AIDS is the most serious stage of infection. AIDS patients have severely compromised immune systems because their CD4 cell count is so low. An AIDS/stage 3 diagnosis is given when a person’s CD4 cell count drops below 200 per cubic millimeter of blood.

How is HIV/AIDS treated?

There is no cure for HIV/AIDs, but treatments are available. These treatments are called antiretroviral therapies (ART). An infected individual should start ART as soon as possible upon diagnosis. ART is a combination of drugs that work to reduce HIV replication (remember those CD4 cells), which therefore reduces the amount of virus in the body (the viral load). The benefits of ART are two-fold. The first benefit is that the CD4 cell population is given a chance to recover and the immune system is able to fight off infection to stay healthy. ART is so effective that it can reduce a patient’s viral load to undetectable amounts. However, this does not mean a patient is cured. If a patient stops taking ART, the viral load will rebound. The second benefit is that ART reduces the risk of HIV transmission. When the viral load is undetectable, the patient has effectively no risk of transmitting HIV through sexual activity. Taking ART as prescribed gives patients with HIV a near-normal life and life expectancy.

A cure for HIV?

In February at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, it was announced to the world that a third person, also the first woman, has been considered “cured” from HIV infection. Wait, didn’t we say there was no cure? Well, yes and no. To date, there is no official cure. Three people out of 37.7 million does not constitute a cure. Patient 3 was being treated for acute myeloid leukemia, a blood cancer, and underwent a stem cell transplant. The stem cell donor had a genetic mutation that made their CD4 cells immune to HIV infection. The patient is described as female, middle-aged, and of mixed race. The donor stem cells came from umbilical cord blood, whereas the previous two cured patients (males) received adult stem cells. This successful treatment is part of a larger study between doctors at the University of California Los Angeles and Johns Hopkins University. This study follows 25 HIV-positive patients who are being treated for cancer and other serious conditions with stem cells isolated from umbilical cord blood.

The stem cell transplant process is not without risk, however. The treatment is intense as a patient must undergo chemotherapy to eradicate the cancerous cells. Stem cells are then transplanted from a donor that harbors a unique mutation called the CCR5-delta 32 mutation, in which their CD4 cells lack a receptor that is necessary for HIV binding. If the virus cannot bind to the CD4 cell, it cannot infect it. If the CD4 cell is not infected and taken over by the virus, the virus has no host to use for replication. Thus, like the donors, these patients become resistant to HIV infection. Patient 3 has been HIV-free for 14 months post-transplant and does not take ART.

This procedure comes on the tail of two previous success stories. In 2007, Timothy Ray Brown, a man with HIV, was receiving treatment for acute myeloid leukemia and received an adult stem cell transplant from a donor who was also naturally resistant to HIV. Brown became the first person officially cured from HIV. This success was repeated with Adam Castillejo, who was being treated for lymphoma in 2016. His stem cell donor also was resistant to HIV infection, and he has been HIV-free for more than 30 months since he stopped taking ART in 2019.

Patient 3’s treatment differs from Brown and Castillejo’s in a few aspects. First, her stem cells came from umbilical cord blood, which is more available and doesn’t need to be as closely matched as the adult stem cells used in the two men’s treatments. The cord blood used for her treatment came from a partial match donor, which is different from the usual process of finding a bone marrow donor that is similar to the patient’s race and ethnicity. To provide her body with temporary immune defense, Patient 3 also received blood from a close relative while waiting for the transplant to take.

The fact that this individual is a woman and of mixed race is important to note. Most bone marrow donors are of Caucasian origin, meaning that finding bone marrow donor matches for non-Caucasian patients can be more difficult. The ability to use a partial match from cord blood may alleviate this problem. Additionally, women make up more than half of the HIV-positive adults worldwide but are vastly underrepresented in curative clinical trials. A 2016 review reported that of curative HIV clinical trials, women comprised only 11% of trial participants. This report of a woman of mixed race being cured of HIV should bring hope to both underrepresented groups.

While this success is exciting, a stem cell transplant is not a suitable widespread option for HIV patients. However, this research has shown that a cure is indeed possible and will no doubt lead to future impactful discoveries in the field.

Edited by Arianna Cascone and Fanting Kung