In the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, Senator Bernie Sanders brought attention to the issue of economic inequality. In the current election season, Senator Sanders denounces rising inequality by making the case that it is unfair that the wealthy use their power and influence to exert control on the economic and political system. Of course, there are those who don’t think this unequal advantage is unfair and argue that it is in fact a beneficial force that spurs innovation.

But outside of this political debate, what does the social science say on the subject of economic inequality? One prominent pair of researchers in this area are the epidemiologists Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, who together wrote the seminal book The Spirit Level that is still commonly cited 11 years after publication. In the book, they present a peer-reviewed epidemiological case for concern about income inequality.

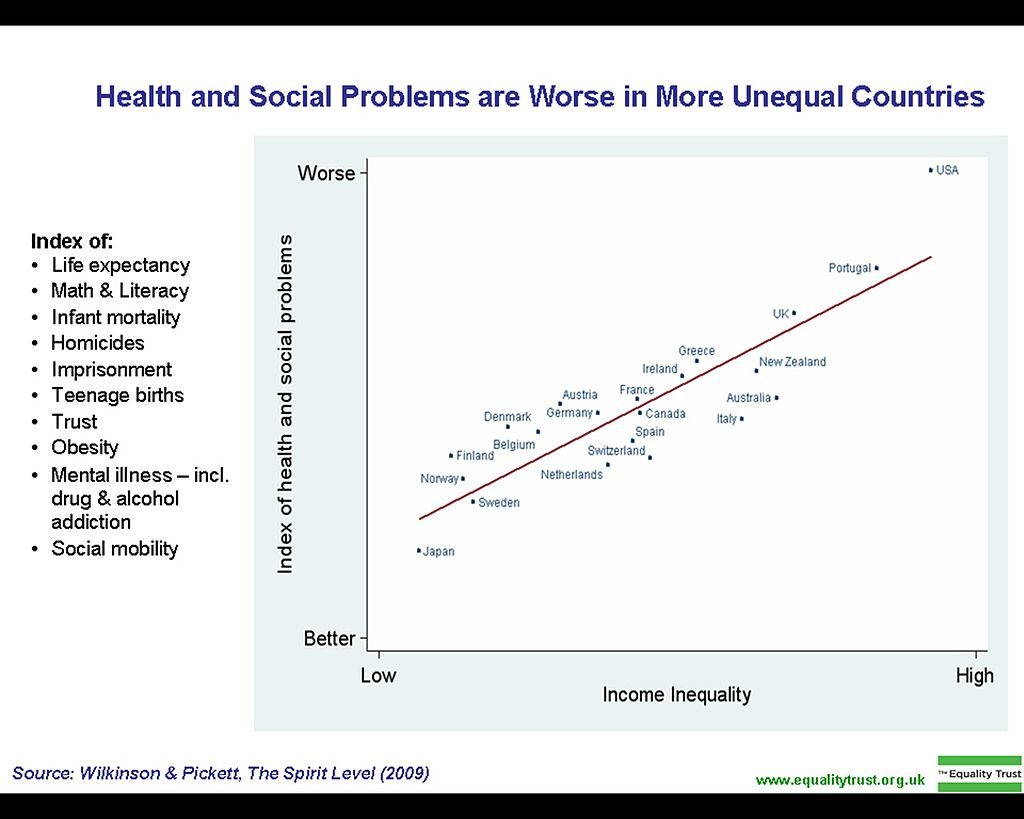

First, they note that among the richest countries, higher national income is only weakly associated with better health and social prosperity. They investigated how social problems in several countries correlate to a measure of economic inequality (called the GINI coefficient) that is simply a numeric value measuring how much richer the top 20% is compared to the bottom 20% of income earners in a given society. To make this comparison, they specifically selected only comparable countries, that is, successful market democracies, such as the US, Canada, Spain, Japan, Australia, and the Scandinavian countries. They argued that a comparison of countries from different developmental stages (such as, comparing the US to Namibia) wouldn’t be interesting since we already know that wealthier and more successful countries are generally better places to live.

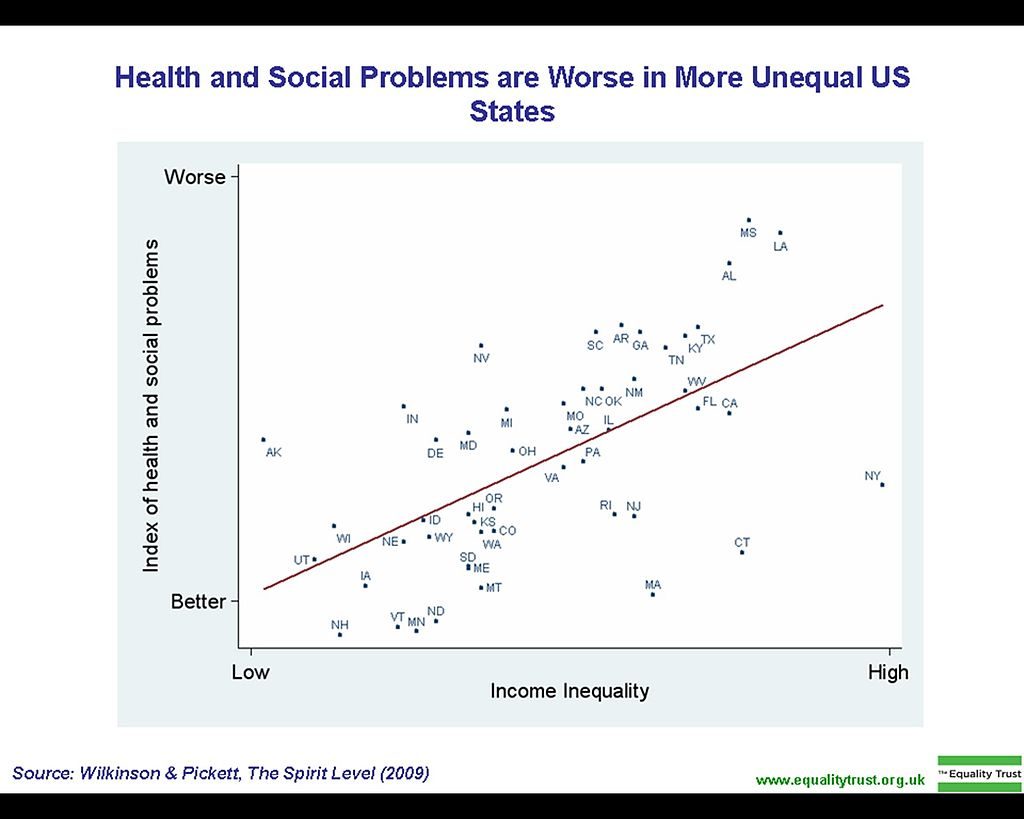

Using existing datasets that measure relevant outcomes across all 21 countries of interest, they created an index of social and health problems that includes a wide variety of outcomes such as level of trust, mental illness (including drug and alcohol addiction), life expectancy, children’s educational performance, teenage births, homicides, imprisonment rates, and social mobility. Pickett and Wilkinson found a strong correlation between this index of social problems and economic inequality across the 21 countries. They also replicated these findings using the UNICEF index of child wellbeing in these same countries. This is an important replication because the UNICEF index has over 40 other indicators of well-being that Pickett and Wilkinson didn’t have a hand in choosing, yet the findings hold. They did another replication using data taken from the 50 states in the US. In each case, economic inequality is a strong predictor of worse social and health problems. It’s important to keep in mind the human cost of these differences. To get an idea of the magnitude of the effects here, compared to the country with the lowest inequality, the country with the most inequality has 8 times the amount of incarcerated people, 2.5 times the prevalence of mental illness, 3 times the amount of obesity, and twice the infant mortality rate.

A spirited political debate continues about how to deal with economic inequality. However, these data make it clear that economic inequality is coinciding with unhealthiness and significant social problems. There is still much work to be done to understand why this strong correlation between economic inequality and social problems exists; the field of social psychology is now studying what might give rise to these trends. Here at UNC-Chapel Hill, psychology professors Keith Payne and Keely Muscatell are investigating how economic inequality influences decision making and health. Ultimately, research has identified the magnitude of the human cost of growing economic inequality; now more must be done to connect this work to the public discourse and policy-making.

Peer Edited by Kaylee Helfrich.

2 Replies to “The Price We Pay for Economic Inequality”