“The greatest scientists are artists as well” – Albert Einstein

We are taught from a young age that our career paths of interest have set boundaries and that those paths will not meet again once they diverge. Science and art are seen as two of the paths that are the most divergent from the other, but they both aim to answer the same questions: “How can I progress and help society?”, “What is true of our current nature?”, and “Why is studying it important?”. It is hard sometimes, even as self-proclaimed artists and scientists, to recognize that the differences we see between the two fields is purely imaginary. To do science, you need the creativity that comes from art; to do art, you need the critical thinking abilities that come from science to interpret the world around us into a representative piece. Even on a more basic and direct level, you need art, such as graphic design, to communicate science and you need to understand scientific properties of your art material to compose the art piece. Nobel Prize winners are shown to be 15–25 times more likely to be engaged in the fine arts as adults than their other peer scientists. 82% of STEM professionals recommend a fine arts emphasis in early education as an essential background for being an innovative scientific thinker. The notion that art and science are fundamentally distinct is one of the longest surviving myths that has persisted into today’s time.

Nobel Prize laureate James P. Allison is an American immunologist at the University of Texas who received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2018. His research “Cancer Therapy by Inhibition of Negative Immune Regulation (CTLA4, PD1)” focuses on the T-cell inhibitory molecular CTLA-4 that downregulates immune responses. By inhibiting CTLA-4, Allison saw anti-tumor immune responses that ultimately led to FDA approval of drugs targeting the T-cell inhibitory pathways as a treatment method for metastatic melanoma. It might come as no surprise given the above discussion that Allison is also a successful harmonica player in his blues band The CheckPoints, which consists of other cancer immunologists. Rachel Humphrey, lead singer of The CheckPoints and chief medical officer of CytomX, says, “Great scientists are creative people. Music and science often go hand-in-hand.”

I want to highlight below some not-as-well-known modern notable polymaths that mastered the art (pun intended) of blending the two fields and showcase some of my favorite artistic and scientific pieces.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer is a Mexican-Canadian electronic artist who holds a B. S. degree in physical chemistry from Concordia University in Montreal. His art pieces play with ideas in architecture and performance art and are heavily reliant on participation through the use of robotics, ultrasonic sensors, LED screens and devices, positional sound, real-time computer graphics, and more. He coined the term “relational architecture” to describe some of his interactive installations. For instance, his piece Solar Equation is a chandelier simulation of the sun that uses five light projectors to animate the solar surface of the sun using live mathematical equations to capture the continuous, never-repeating visual of turbulence sunspots and flares on the sun’s surface.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer is a Mexican-Canadian electronic artist who holds a B. S. degree in physical chemistry from Concordia University in Montreal. His art pieces play with ideas in architecture and performance art and are heavily reliant on participation through the use of robotics, ultrasonic sensors, LED screens and devices, positional sound, real-time computer graphics, and more. He coined the term “relational architecture” to describe some of his interactive installations. For instance, his piece Solar Equation is a chandelier simulation of the sun that uses five light projectors to animate the solar surface of the sun using live mathematical equations to capture the continuous, never-repeating visual of turbulence sunspots and flares on the sun’s surface.

Janet Saad-Cook

Janet Saad-Cook describes her art as “[lying] at the intersection of light and space and time.” She uses light that comes from the sun and ancient sun marking techniques with modern technology to create sun drawings. She works closely with engineers, physicists, and architects to accomplish her art pieces. Her sun drawings constantly evolve with the time of day and aim to orient viewers in their relative position in time and space.

Janet Saad-Cook describes her art as “[lying] at the intersection of light and space and time.” She uses light that comes from the sun and ancient sun marking techniques with modern technology to create sun drawings. She works closely with engineers, physicists, and architects to accomplish her art pieces. Her sun drawings constantly evolve with the time of day and aim to orient viewers in their relative position in time and space.

Anicka Yi

is a conceptual artist who engages the human sensory system to portray her art pieces. She was born in Korea and immigrated to the US when she was two years old.  She began exploring her unorthodox experimentation with art, science, and scent at the age of 30. She often uses live perishable items in her pieces and works very closely with scientists at Columbia University and MIT to use biological material in her art pieces. Her piece You can call me F uses bacteria collected from 100 women who were given the choice of where to take the swab collection and grown on an agar billboard to represent a physical visual answer to the question “What does feminism smell like?”. Another piece called The Flavor Genome is a 22 minute 3D video exploring the themes of bioengineering and imperialism.

She began exploring her unorthodox experimentation with art, science, and scent at the age of 30. She often uses live perishable items in her pieces and works very closely with scientists at Columbia University and MIT to use biological material in her art pieces. Her piece You can call me F uses bacteria collected from 100 women who were given the choice of where to take the swab collection and grown on an agar billboard to represent a physical visual answer to the question “What does feminism smell like?”. Another piece called The Flavor Genome is a 22 minute 3D video exploring the themes of bioengineering and imperialism.

Other art installations:

Remote Sensing 38 by Suzanne Anker, pioneer in BioArt.

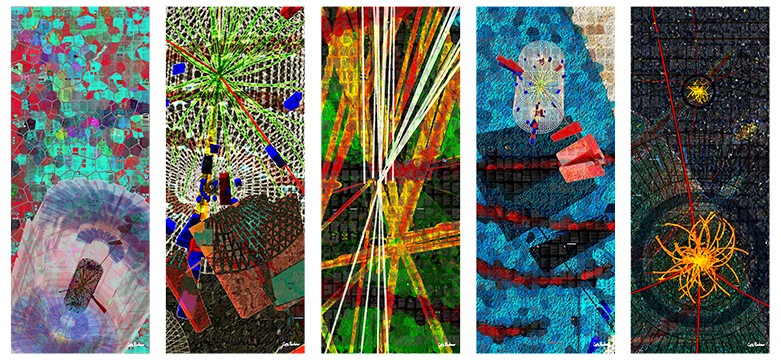

In Search of the Higgs Boson by Xavier Cortada, inspired by the Nobel prize-winning discovery of “the God particle” by Pete Markowitz.

Titan by Daniel Zeller, part of the NASA | Art: 50 Years of Exploration exhibition.

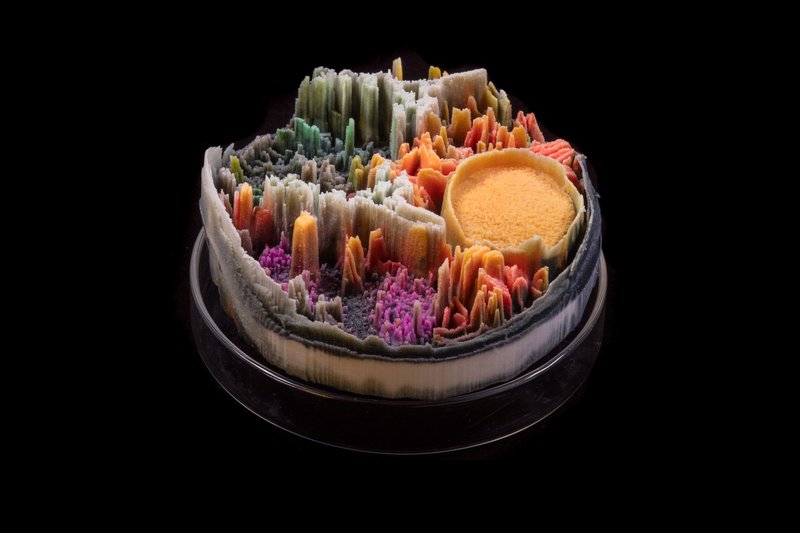

Treasure of Great Price by Elizabeth Busey inspired by ancient topography.

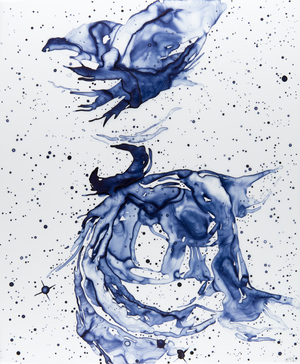

Deep Sky Companion by Lia Halloran, inspired by astronomy.