At its core, the hydrologic cycle is a fairly intuitive concept. Water precipitates from the sky, runs off the land and into the ocean. Then the water evaporates into clouds, and falls again as rain or snow, starting the endless cycle all over again. However, nature rarely follows such a linear path, especially when it is affected by human activity and a changing climate. Over time, humans have had such a profound impact on the planet that scientists are debating whether to designate an entirely new geological epoch to reflect these changes. In this article, we explore Earth’s water cycle and the effects humans are having on the natural world.

Interested in seeing how much water you or your household use daily?

Easily find out using the Water Consumption Calculator (English/Spanish)!

The Anthropocene

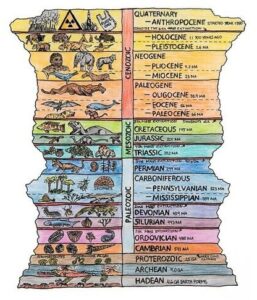

The geologic time scale (over 4.5 billion years) is separated into 22 distinct periods of time, ranging from millions to tens of millions of years, and each period is further separated into epochs (hundreds of thousands to tens of millions of years). The delineation between epochs is dependent on the shifts in the diversity of life and climate on Earth (Figure 1). The Anthropocene is the proposed geologic epoch marking the portion of time when humans are having an increasingly significant effect on Earth’s biodiversity and climate. Much like the worldwide iridium deposits from the asteroid impact that defines the end of the Age of Dinosaurs (~65 million years ago), the Anthropocene is marked by the radioactive deposits from the first atomic bombs dropped in the 1950s.

Our Freshwater Resources

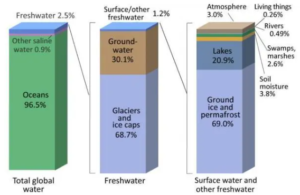

While Earth is often referred to as the “blue planet” for its abundance of water, only a small percentage of that water is actually drinkable. With over 362 million trillion gallons of water on Earth, only 2.5% of it is accessible for freshwater resources (Figure 2). The majority of freshwater is frozen in glaciers (1.7%), while the rest is stored as groundwater (0.75%) and surface water (0.03%). Freshwater accessible on the surface includes all lakes, rivers, swamps, and permafrost, as well as atmospheric and soil moisture. Even with 2.7 trillion gallons of accessible water, the distribution is uneven across the planet. Some regions, such as tropical rainforests, have an abundance of water, while others, such as the American Southwest, are water-poor and must allocate water use very carefully. This shortage of such a vital resource can lead to water scarcity in many regions, which can have a negative impact on human health, agriculture, and the environment in the short and long term. Scientists say that the increasing scarcity of water in the American Southwest could be the longest megadrought in history (2000-2023) since 800CE.

A Human-Influenced Water Cycle

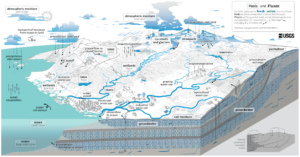

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) unveiled an updated water cycle diagram in January 2023 (Figure 3), now including the roles humans are playing. The new diagram not only depicts the classic system of precipitation, condensation, and evaporation, but also the anthropogenic processes such as agricultural, industrial, and domestic water use, as well as reservoir development and urban runoff for example.

This diagram is a more modern representation of how complex our water cycle is and shows the ways in which humans are affecting it. Since the invention of aqueducts in ancient Egypt, humans have been redirecting water for our own use and supply. Now with the development of dams to form reservoirs, draining of wetlands for urban development, as well as the channelization and redirection of rivers, we are changing how water moves across the land. We are also pumping water from subsurface aquifers, and run the risk of overdrawing and not allowing enough time for the aquifers to recharge. Overdrawn aquifers impose threats not only of water scarcity but also land subsidence, as seen in California’s Central Valley, which can cause natural and infrastructure hazards.

Actions Moving Forward

- Eat less meat and processed foods to reduce water withdrawals for agriculture.

- Air dry your clothes to reduce hydro-powered electricity consumption.

- Plant native grasses and flowers instead of manicured grass to reduce lawn watering.

- Take public transportation or ride a bike to reduce oil extraction and gas consumption.

Recognizing the implications of our actions on the water cycle is vital for preserving freshwater resources. To contribute to water sustainability in our day-to-day lives, we can promote responsible practices by conserving water through mindful consumption, adopting water-saving technologies and practices, and supporting efforts to protect and restore endangered ecosystems.

Peer editor: Elise Edgar