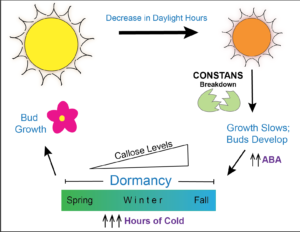

When the days suddenly seem shorter and the nights are colder, you know fall has arrived. You especially know it’s here when the leaves gain a reddish hue and soon after fall from the trees by the truckload. In fact, the name ‘fall’ has been used in America since the 17th century, shortened from the English phrase “leaves falling from the trees.” Fall technically begins with the autumnal equinox in late September, when the hours of daylight and night are the same. At this point, perennial trees, or trees that grow year after year, have two tasks: 1) to stop growing leaves and instead prepare flower buds for next spring, and 2) to protect those buds from winter’s cold. First, we must ask how trees sense changes in daylight in the first place?

Hybrid aspen trees (which are most often used in plant science to study genetics and growth regulation) have light and color detectors that respond to levels of light. One response is the activation of a protein called CONSTANS, which controls growth genes but gets broken down in the absence of light. In that regard, as the days grow shorter and there is more darkness, CONSTANS becomes less stable and leaf growth slows. The slowing of leaf growth marks the beginning of a process when the plant uses much of its remaining energy to form a bud, or an immature flower. This bud will bloom the following spring, but it needs protection from the cold and often dry climate brought on by winter. In addition to the bud, a multi-layered and extremely hardy outer shell is formed to protect the bud from the cold and drying out. The process of forming a bud is highly variable between plant species, but typically lasts 6-10 weeks. After the bud and its protective shell have formed, almost all plants in the Northern hemisphere enter the ‘dormancy’ phase to survive the winter.

To protect against drying out and cold temperatures, it is important that a bud receives no growth signals during dormancy. As buds are formed in trees, a plant hormone called abscisic acid, or ABA, encourages the production of callose, a starchy sugar that blocks signaling between plant cells. During dormancy, ABA maintains callose production, but becomes less effective as daylight hours increase. Even after ABA loses its effect (when we reach a certain amount of daylight hours), buds are still protected by callose, which is broken down slowly by prolonged low temperatures. Callose protects the plant by preventing it from growing during random hot spells in January and February, when there are more daylight hours, but temperatures will likely drop again. When there have been enough hours of cold (~30-55 °F), all callose will be broken down and the bud will slowly start receiving signals to grow. The accumulation of growth signals and the right temperature (usually above 60°F) will tell the tree to open its buds and start growing. One potential problem with this system is that if a frost comes after the buds have opened, they might become damaged from the cold and won’t produce flowers or fruit. However, as temperatures warm and the days get longer, the risk of frost decreases.

The spring equinox will mark the shift into longer days, and often coincides with trees exiting dormancy with an explosion of growth by the buds they formed in the previous the fall. These buds will rapidly cover the tree with beautiful green leaves, highlighting the beginning of the transition to the long, languid days of summer.

Peer Edited by Keean Braceros.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: