This fall, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Michael Mayor and Didier Queloz for the first discovery of an exoplanet – a planet orbiting a star other than our sun. In the 31 years since that discovery, thousands more have been found. There are a few methods to find exoplanets. One of the most common is transit photometry, which involves looking for the change in brightness of a star as a planet crosses between us and it. When a planet crosses between a star and us, that is called a transit, and it is detected via transit photometry. Transit photometry is fairly easy in theory, and allows you to find a planet in just three (sort of) easy steps.

Step 1 – Pick a Star

The easy part: Astronomers believe that most stars in the galaxy have at least one planet around them, so almost any star you pick should have an exoplanet.

The hard part: Detecting planets is hard in areas with many stars packed closely together, and planets might not form in those areas at all. Additionally, even if your star has planets, the likelihood that they line up exactly right to detect a transit is pretty low, so you’ll have to look at more than one to get lucky.

Step 2 – Look for a Transit

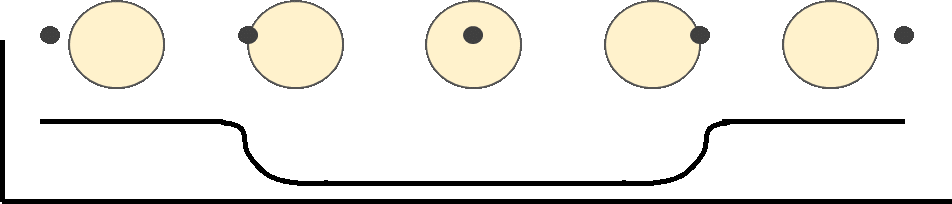

The easy part: Once you’ve picked a star to look at you’ll want to observe it for as long as you can. A planet crossing the star produces a distinct rectangular dip in the brightness of the star, so if you see something like that you’ve probably got a transit.

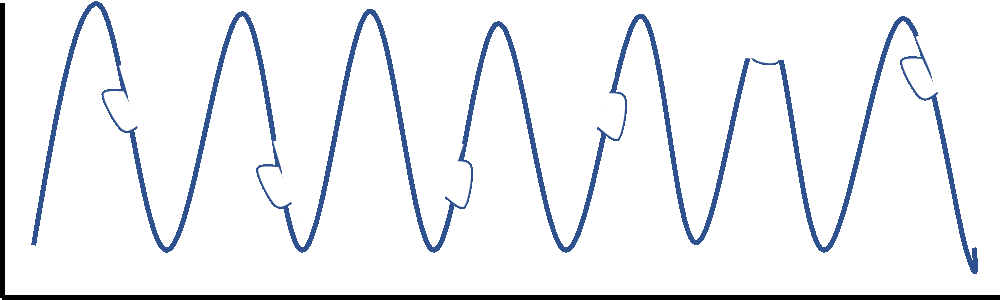

The hard part: In a perfect case, the transit would look like the example above. But some stars don’t produce light constantly and most planets aren’t big enough to cause more than a 1% dip in the light of the star. So, the transit ends up being a little bump in a noisy and changing light curve.

Step 3 – Look for more Transits

The easy part: You’ve found a transit! Congrats! Now you need to find more. Without multiple transits from the same planet it’s hard to prove it wasn’t just a fluke. To find more just go back to your star and look some more.

The hard part: You might get lucky if your planet orbits its star quickly, like the TRAPPIST planets, which all orbit the star in less than a week. Or you might get really unlucky, and find a planet with an orbit like Neptune – once every 163 years. If you’re on the lucky side you’ll see another transit after one orbit, and even more if you wait for them. Then, you can announce your planet discovery to the world!

Peer edited by Elise Hickman