The world of science is filled with inequalities and biases of many different kinds. In India – where I’m from – this exclusion begins at a very young age due to our colonized past, with children from rural or lower class urban areas not receiving the same access to good education, particularly English language education. Although there should be absolutely no need for Indian children to speak a European language to prove their competence, the harsh realities of our postcolonial world dictate that it is a much harder endeavor for those who do not speak English well, or at all, to get as far as those who do. Outside of language barriers, India also has a flourishing caste hegemony that’s tied very deeply with social othering and economic backwardness. To this day, a person’s caste can decide which educational, employment, and housing opportunities they have access to, causing a very large chunk of the Indian population, particularly Indian women, to never even have the option of pursuing a career in science.

This is, of course, not an isolated problem in just India. Many of these oppressive systems exist across the world and do not stop at the university gates or laboratory doors. Even those who have made it into these hard-to-reach rooms struggle regularly to prove to those around them that they belong there, that they should be allowed to stay. Phenomena such as the leaky STEM pipeline, for instance, highlight existing issues with retainment of scientists from under-represented communities.

While these are pressing problems for today’s world of science, there is a different form of systemic bias that I’d like to bring attention to in this article. In academia, publications are often seen as a sort of universal currency. From getting into graduate school, to tenure, to grant funding, we rely on publications, which are considered a representation of our creativity, innovation, productivity, etc. However, in a universe where articles, journals, editors, and publishers are so important, who decides what facts need to be published? Who makes sure that a study isn’t contributing to the strengthening of existing oppressive and exclusionary systems?

Who checks to see whether publishing a study does more harm than good?

The answer, currently, seems to be no one. Here are four examples of papers that have come out in top journals (within the last decade) that would have benefited from more rigorous checks and balances existing in the publishing world:

- “Attractiveness of women with rectovaginal endometriosis: a case-control study”

This 2013 paper by Vercellini et al., published in the Elsevier journal Fertility and Sterility, studied 300 women with or without endometriosis and evaluated their physical attractiveness, based on factors such as large breasts and lean silhouettes. Attractiveness was measured using a graded scale by four independent male and female observers who concluded that women with rectovaginal endometriosis were more attractive than women who didn’t suffer from this condition. Even without getting into the question of what this study was ever hoping to accomplish, it is very hard to condone the authors’ methods of judging attractiveness. Although this paper was eventually retracted in November 2020, the fact that it took nearly 8 years to do so is very telling of how many men see women and their existence in today’s society.

- “Borderline personality traits in attractive women and wealthy low attractive men are relatively favoured by the opposite sex”

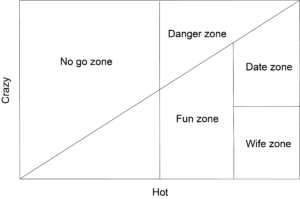

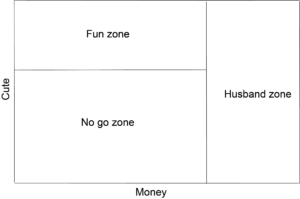

This 2021 paper by Blanchard et al., published in the Elsevier journal Personality and Individual Differences, studied “sex differences in partner preferences” by asking participants of the study to measure attractiveness and borderline personality disorder (BPD) traits in women, and attractiveness and wealth in men. Through the use of measures such as the Hot-Crazy Matrix and the Cute-Money Matrix, they observed that men were happy to be in relationships with women who were high in BPD traits as long as they were attractive, while women “compensated low attractiveness in men for wealth”. The authors’ liberal use of the word “crazy” in relation to BPD traits, as well as the study’s basis on matrices that stem from ridiculous and potently misogynistic societal ideas, makes this study both dehumanizing and extremely insulting. As of the publishing of this article, this paper has not been retracted.

- “Large-scale GWAS reveals insights into the genetic architecture of same-sex sexual behavior”

This 2019 Science paper by Ganna et al. reported the results of a large genome wide association study that identified five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) correlating with ever having had a same-sex partner. They concluded that same-sex sexual behavior isn’t controlled by any one gene (i.e., there is no “gay gene”) and is instead influenced by the complex and coordinated action of many different genes. Immediately following the publishing of this paper, it received many criticisms, particularly directed towards the fact that this study does not take into consideration the social and historical context of its participants, all of whom were from two countries (the UK and the US) and were also born in the same time period. The study also begs the question: what would the consequences of finding a single “gay gene” have been in today’s societal and scientific landscape, where homophobia and oppression are truths, and genome editing technologies are a growing possibility? As of the publishing of this article, this paper has not been retracted.

- “The association between early career informal mentorship in academic collaboration and junior author performance”

This 2020 paper by AlShebli et al., published in Nature Communications, studied sex differences in informal scientific mentorship and concluded that female mentees advised by female mentors were at a disadvantage, and vice versa. Although the authors spin this study as an attempt to improve the impact of women in science by suggesting that opposite-gender mentorship is the more advantageous mentor-mentee combination, it very obviously ignores the social and historical context of systemic gender oppression while contributing heavily to damaging the careers of female mentors. This article was retracted in December 2020.

These are just four examples of studies that, in my opinion, should never have been published. It is almost certain that there are many others of the same caliber (or worse) that have also made it through the peer review process. Is it not bordering on criminally oppressive to not hold these authors, reviewers, editors, journals, and publishing companies accountable for the damage they are doing to already underrepresented and marginalized groups? Any successful experiment will provide the researcher with information about the subject under study, and if experiments are performed with appropriate rigor, that information may very well be fact. However, the real question here is whether all facts need to be published. Do all facts have the same impact, and more importantly, do all facts have the same impact across different sections of society?

Is a fact really a fact when the societal context in which it supposedly exists isn’t presented at all?

It is hard to argue that a research study whose results do more harm than good is a valuable addition to our world. Scientists spend huge amounts of time, effort, and (often taxpayer) money in performing their experiments and publishing their findings, and I am of the opinion that works such as the papers mentioned above are absolutely not worth the expenditure of these resources.

As scientists, we love to claim that science is about objectivity and truth. However, I think it’s more important that we not be blind to the societal context in which our lives, and the science we put forth, exist. It is good to periodically remind ourselves that we do not live in an isolated bubble – everything we do has socio-political consequences. The power (and funding) that scientists are given to conduct research should also come with a grave sense of responsibility to the people living in this world that we are paid to study.

Peer edited by Kaylee Helfrich and Isabel Newsome