Let’s start at the very beginning. When a mammalian egg is successfully fertilized by a single sperm, the result is a single cell called a zygote. A zygote has the potential to grow into a full-bodied organism. It is mind-boggling that this single cell, containing the genetic material from both parents, can divide itself to make two cells, then four cells, then eight cells, and so on, until it becomes a tiny ball of 300-400 stem cells.

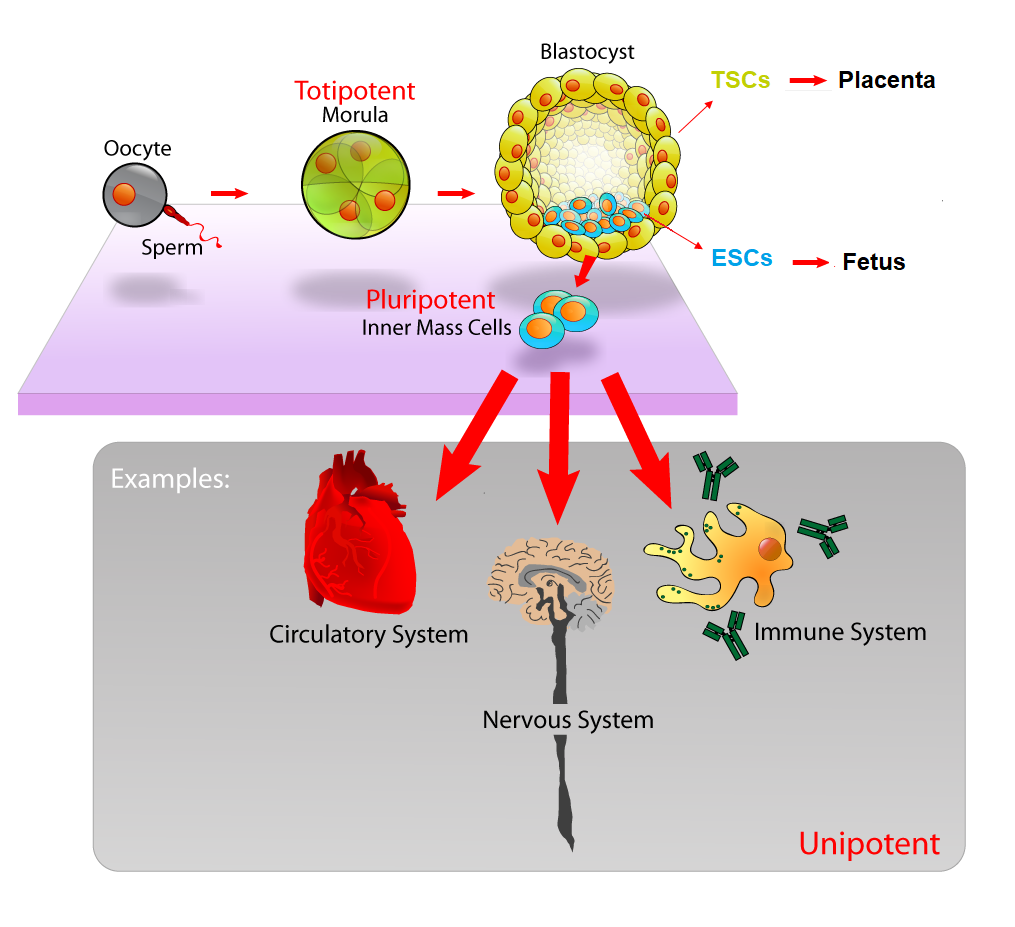

At these early stages, these stem cells are totipotent, meaning that they have the potential to become either embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which will eventually become the fetus itself, or extraembryonic trophoblast cells (TSCs), which go on to help form the placenta. That ball of ESCs and TSCs develops into a blastocyst with a tight ball of ESCs on the inside, and a layer of TSCs on the outside (See Figure 1).

You might imagine the blastocyst as a pomegranate, with the seeds representing the ESCs and the outer skin representing the TSCs. The ESCs have the potential to transform, or differentiate, into any type of cell in the entire body, including heart cells, brain cells, skin cells, etc., which will ultimately become a complete organism. The outer layer TSCs have the ability to differentiate into another type of cell that will ultimately attach itself to the wall of the uterus of the mother to become the placenta, which will provide the embryo with proper nutrients for growth.

Scientists in the field of developmental biology are absolutely bonkers over this early stage of embryogenesis, or the process of embryo formation and development. How do the cells know to become ESCs or TSCs? What tells the ESCs to then differentiate into heart cells, or brain cells, or skin cells? What signals provide a blueprint for the embryos to continue growing into fully-fledged organisms? The questions are endless.

The challenge with studying embryogenesis is that it is incredibly difficult to find ways to visualize and research the development of mammalian embryos, as they generally do all of their growing, dividing, and differentiating inside the uterus of the mother. In recent years, there have been multiple attempts to grow artificial embryos in a dish from a single cell in order to study the early stages of development. However, previous attempts at growing artificial embryos from stem cells face the challenge that embryonic cells are exquisitely sensitive and require the right environment to properly coordinate with each other to form a functional embryo.

Enter stage right, several teams of researchers at the University of Cambridge are successfully conducting groundbreaking research on how to grow artificial mouse embryos, often called embryoids, in a dish.

In a paper published in Development last month, David Turner and colleagues in the Martinez-Arias laboratory report a unique step-by-step protocol developed in their lab that uses 300 mouse ESCs to form tiny balls that mimic early development.

These tiny balls of mouse ESCs are collectively termed “Gastruloids” and are able to self-organize and establish a coordinate system that allows the cells to go from a ball-shape to an early-embryo shape with a head-to-tail axis. The formation of an axis is a crucial step in the earliest stages of embryo development, and it is exciting that this new model system may allow scientists to better study the genes that are turned on and off in these early stages.

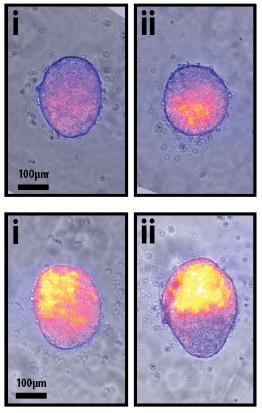

In a paper published in Science this past April, Sarah Harrison and her team in the Zernicka-Goetz laboratory (also at Cambridge) report another technique in which mouse ESCs and TSCs are grown together in a 3D scaffold instead of simply in a liquid media. The 3D scaffold appears to give the cells a support system that mimics that environment in the uterus and allows the cells to assemble properly and form a blastocyst-like structure. Using this artificial mouse embryo, the researchers are attempting to simulate the growth of a blastocyst and use genetic markers to confirm that the artificial embryo is expressing the same genes as a real embryo at any given stage.

The researchers found that when the two types of stem cells, ESCs and TSCs, were put together in the scaffold, the cells appear to communicate with each other and go through choreographed movement and growth that mimics the developmental stages of a normal developing embryo. This is enormously exciting, as models like this artificial embryo and the Gastruloid have the potential to be used as simplified models to study the earliest stages of embryo development, including how ESCs self-organize, how the ESCs and TSCs communicate with each other to pattern embryonic tissues, and when different genetic markers of development are expressed.

It is important to note that this artificial embryo is missing a third tissue type, called the endoderm, that would eventually form the yolk sac, which is important for providing blood supply to the fetus. Therefore, the artificial embryo does not have the potential to develop into a fetus if it is allowed to continue growing in the dish. The fact that these artificial embryos cannot develop into fully-fledged organisms relieves some of the controversial ethical issues of growing organisms in a dish, and will allow researchers to study critical stages of development in an artificial system.

These techniques and discoveries developed by these teams of researchers have the potential to be applied to studies of early human development. These models may prove especially useful in studying how the maternal environment around the embryo may contribute to fetal health, birth defects, or loss of pregnancy. In the future, artificial embryos, coupled with the not-so-futuristic gene editing techniques that are currently in development to fix disease genes, may prove key in the quest to ensure healthy offspring.

Peer Edited by Nicole Smiddy and Megan Justice.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article:

Such a clear explanation. Thanks for helping this physical science person to understand some life science!