Think back to when you learned about bacteria in school. How did your teacher describe them? Maybe they said that bacteria are invisible to the naked eye, are the causes of many diseases, or lack a nucleus. One descriptor your teacher almost certainly used was single-celled. Unlike a human, where trillions of cells work together to make a single living creature, bacteria are single-celled creatures – they have everything they need to live an independent life in one cell. We generally accept this as part of the definition of bacteria, but there is an exception.

As early as the 1980s, microbiologists knew of a group of bacterial species that are also multicellular organisms. These species have gone by many names over the years – magnetotactic multicellular aggregates, many-celled magnetotactic prokaryotes, and magnetotactic multicellular organisms. But they’re all defined by two traits – their multicellular structure and their ability to align with and move along the earth’s magnetic field. While the latter trait is fascinating, it’s known to exist in some other bacteria. Multicellularity, however, is not.

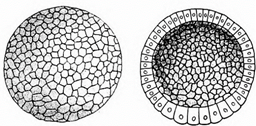

Researchers in Brazil (where these organisms were first discovered) named one of the species Candidatus Magnetoglobus multicellularis. It has become the most well-studied member of the multicellular bacteria, though no one has been able to grow it in a lab (giving it the status of Candidatus, since growth in a lab is required for a bacterium to become a named species). In nature, Ca. M. multicellularis takes the form of a sphere of cells with a hollow center. It’s similar to the shape of the blastula, one of the key stages in the development of embryos in humans and other animals.

Those familiar with microbiology might say that plenty of bacteria live in clusters of cells, and we don’t consider them multicellular. It’s true; colonies, biofilms, and other microbial superstructures all involve bacteria in close proximity, often working together for survival. However, these cells still behave and replicate individually. The cells in the sphere of Ca. M. multicellularis not only travel as a unit, but also are synchronized in their reproduction – cells physically grow in size, then one sphere splits into two identical spheres. We know of no instances where Ca. M. multicellularis exists as a single cell in nature. Researchers have been able to break up the spheres into single cells, but these cells never survived.

Candidatus Magnetoglobus multicellularis meets nearly all the defining characteristics of bacteria – we couldn’t realistically classify it as any other type of organism. Yet, it brazenly defies what we consider a core trait among all bacteria. Its multicellularity is just one example of the incredible ability of microorganisms to break the rules we set for them. In this way, studying microbiology constantly reminds us to question what we think we know.

Peer edited by Anneliese Long

Where one draws the line on multicellularity is open to debate, but Magnetoglobus multicellularis is not the only arguably multicellular prokaryote. A variety of cyanobacteria such as Nostoc and Anabaena show cellular differentiation. The Wikipedia article on multicellularity lists 5 prokaryote groups with multicellular members.

Great point! Though I’ll say that M. multicellularis is the only known obligate multicellular prokaryote – its apparent inability to survive in a single-celled form and its replication as a single unit differentiates it from other kinds of prokaryotic multicellularity! Though we haven’t really decided where to draw that line, you could argue that it’s the “most” multicellular. See Lyons & Kolter (2015): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4380822/