The Black Lives Matter protests and associated high profile cases of police violence against unarmed Black men has catalyzed a conversation about race in the US. However, the problem of racial inequality extends far beyond policing. Racial inequality has a deep history in the US and despite the struggles in the Civil Rights Era that resulted in (mostly) legal equality, there is still vast inequality between Black and white citizens in practice.

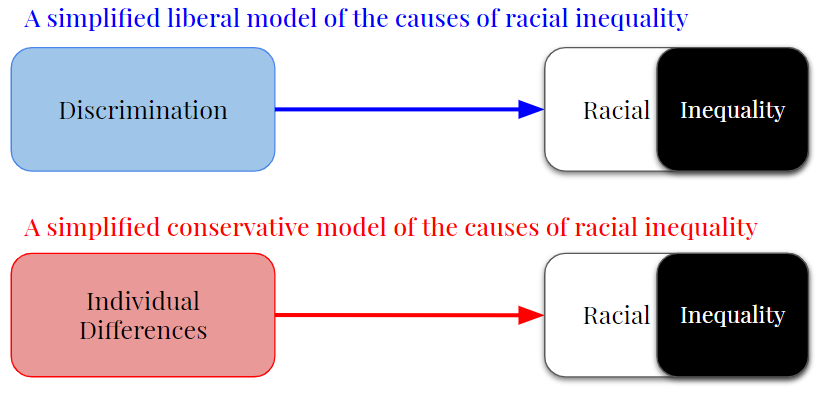

It is hard to overstate just how clear the evidence is for the claim that racial inequality is an ongoing problem in the United States. While there are probably a handful of people who would deny this reality, most people across the political spectrum agree that there is racial inequality. Where people disagree is on the question of why there is racial inequality. There are essentially two competing narratives: 1) “Racial inequality is caused by historical and ongoing discrimination,” or 2) “Racial inequality is due to differences in choices, culture, and/or values.” The former narrative emphasizes that the Black community has been (and continues to be) held back by racism on an individual and systemic basis. The latter narrative emphasizes the legal equality that Blacks and whites share and thus attributes disparities to differences across individuals in each group.

Which of these narratives one endorses is highly correlated with their demographic group. Conservatives (compared to liberals), are more likely to adopt the latter narrative. In other words, they are much less likely to agree that discrimination is the main reason Black people can’t get ahead. Similarly, whites (compared to Black Americans), are much less likely to cite discrimination, lower quality schools, and lack of jobs as the causes of inequality. The polls cited above also show there are similar racial and ideological splits on perceptions of the Black Lives Matter movement. Beyond this polling data, you can find plenty of examples of these narratives emerging out of their respective demographic camps.

In the conservative magazine National Review, attorney Peter Kirsanow argues that “individual behavior, family structure, perverse governmental policies, and culture” are largely ignored when discussing racial inequality. He also claims that “systemic, structural, or institutional racism” are over-emphasized by liberals in a politically convenient ploy. Popular conservative commentator Ben Shapiro echoed this perspective here saying racial inequality, “has nothing to do with race, and everything to do with culture.”

The alternative narrative, that racial inequality is caused by historical and ongoing discrimination, is actually quite widespread in the news media even within outlets that are somewhat “down the middle”. For example, this USA Today article connects disparities in police violence and coronavirus deaths to systemic racism. The author argues that aspects of racial inequality are “intimately connected” and points to a legacy of discrimination as the cause of current housing disparities between white people and Black people. For a more liberal example, this Mashable article succinctly claims that systemic racism “is everywhere” and also links it to racial disparities related COVID-19 and high profile policing deaths.

Experimental research

The statistics about racial inequality are basically correlations. Being Black is correlated with a variety of disadvantages; being white is correlated with a variety of advantages. So how can we understand what causes these advantages and disadvantages? Well, how do scientists typically establish causation? The best tool scientists have to determine cause and effect is the Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT). In an RCT, researchers randomly assign participants to a treatment condition, where they undergo some sort of intervention, or to a control condition. Since the assignment to condition is random, we can assume that any differences between the treatment and control conditions are the result of the intervention, since without it the groups would be the same. This methodology is the gold standard for investigating the cause of something. However, in many cases, there are practical and ethical reasons for why we cannot do the experiment we would need to do in order to fully establish causality.

As an example, take the assertion that racism is responsible for an academic achievement gap between Black people and white people. This claim could be experimentally tested by exposing white and Black children to racism against their groups, and then testing their academic achievements. We would want to control for other factors, so the children would need to be moved to three isolated communities that are treated identically except for how they are treated in terms of their race. In one community, the white children would be taught about the long history of their subjugation and then be subject to systemic and individual discrimination. In another community the Black kids would get this treatment. In the control, there would be no racial inequality or discrimination. We would test them every year for ten years to see what the effect of racism is on the achievement gap. Clearly, the above example would be an ethical nightmare. There is no way to (ethically) randomly assign the things that are said to cause racial disparities we see in society. We cannot randomly assign people to be white or black, or to be subjected to racism and discrimination, or to have specific values and culture. However, scientists have found ways to conduct ethical experiments to test the effects of discrimination.

For example, consider disparities such that compared to white people, Black people were less likely to be employed, more likely to be in poverty, have about 10% of the net worth of whites, and have half the median income of white people. Is there any experimental evidence that this situation is the result of discrimination? The quick answer is yes. Hiring discrimination occurs when equally qualified Black people are less likely to receive a job offer than their white counterparts. Researchers study this phenomenon through what are called “hiring audit studies”. In these hiring audit studies, researchers respond to job advertisements with 2 job applications that are identical in every way except the race of the applicant (usually using a Black-coded name like “Jamal” vs a white-coded name like “Steve”). In 2017, a meta-analysis representing data from 28 previous hiring audit studies found evidence of racial bias in hiring such that whites receive 36% more callbacks than identically qualified Black people. They also did not find evidence that this level of discrimination had changed over the last 25 years. These experiments demonstrate that discrimination has been happening for the last few decades and is currently ongoing, and it is keeping qualified Black people out of work.

Over this same period of time, dozens of similar audit studies have been completed to detect housing discrimination, where Black prospective home-buyers or renters are denied housing while identically qualified white buyers or renters are welcomed to the neighborhood. In these studies, there are white and Black auditors who submit housing applications with identical information, except the person submitting the application is either Black or white. Often, the auditors are even trained to give the same responses during interactions with realtors. Again, scientists here try to control for every other conceivable factor besides race. In a meta-analysis representing 72 housing audit studies in the US, Canada, and Europe, researchers evaluated the level of housing discrimination since the 70s. During the 70s through the 90s, Black people were about 50% less likely to receive a positive response from a housing application compared to whites. Other studies showed that discrimination decreased after the 90s so that Blacks are only 25% less likely to receive a positive response on a housing application. The most recent estimate shows that Black people today are still about 15% less likely to get those positive responses compared to whites. While it has decreased, this current level of discrimination still represents a significant difference in how equally qualified Black people and white people are treated. Worse still, this decrease has coincided with other forms of housing discrimination such as on Airbnb where applications from accounts with Black names are 16% less likely to be accepted relative to identical white accounts. Homeownership is an effective way of building wealth, particularly for low-income and minority households, so housing discrimination has likely had important downstream effects that have contributed to economic inequality across the generations.

Economic discrimination between equally qualified Black and white people is found in a variety of domains, such as car purchasing, getting home insurance, getting a mortgage, and even hailing a taxi! The discrimination Black Americans face is sickening–literally. A 2015 meta-analysis documented that experiences with discrimination and racism in day-to-day life predicts poorer health for Black people. Data taken from 293 studies showed that reported racism predicted both poorer mental and physical health. Even within the doctor’s office, patients cannot escape the effects of racial discrimination. An audit-style study was done with physicians making recommendations about Black and white patients portrayed by actors with identical histories. Black patients were less likely to be referred for potentially life-saving treatment compared to whites with the same clinical presentation. Doctors have been found to harbor a racial bias that Black people are less sensitive to pain (which is likely the opposite of what is true) and thus under-prescribe pain medication to Black patients. But the effects of bias extend beyond just pain treatment. A 2015 systematic review found that racial bias of medical professionals predicts racial disparities in treatment decisions, treatment adherence, patient-provider interactions, and ultimately patient health.

…discrimination has been happening for the last few decades and is currently ongoing, and it is keeping qualified Black people out of work.

The evidence is clear: discrimination does indeed cause racial disparities. It’s important to recognize that these studies demonstrate discrimination between otherwise identical people. In the audit studies I reviewed above Black people weren’t discriminated against for being poor, or uneducated, or having a criminal background. All of that is controlled for in these studies. These studies demonstrate in no uncertain terms that Black Americans in the modern era are being discriminated against simply because of their race. As discussed above, racial discrimination accounts for some significant portion of disparities in employment, income, wealth, housing, transportation, and medical treatment. Black people are even discriminated against in the primary domain they have to meaningfully influence the policies that could change this situation: voting.

But, what about the conservative position that individual factors cause racial disparities? We run into a bit of a problem at this point; while researchers have cleverly devised a way to experimentally measure the effects of discrimination through audit studies, there is no way of auditing the effects of culture, choices, motivation and/or values. To credit the conservative position, psychologists study individual differences in choices, cultural orientation, values, or behavior, and we know that these things play a role in success. But again, this is correlational. How do we know if these individual factors play a causal role in racial inequality?

Well, in some sense this topic is at the center of a lot of academic research. Researchers in psychology often cannot experimentally change the systematic factors related to racial disparities (like policy-makers could), so they come up with interventions to influence characteristics of individuals to help alleviate gaps. For example, Black students who enter college often do not feel a sense of belonging and this lack of perceived belonging is linked to worse academic outcomes for Black students compared with white students. Researchers designed an intervention where participants read stories from other students that encouraged participants to think about belonging as something that develops over time and strengthens as you make connections with students and faculty. This simple one-time intervention was replicated across a wide variety of schools and resulted in a 31-40% decrease in the achievement gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students.

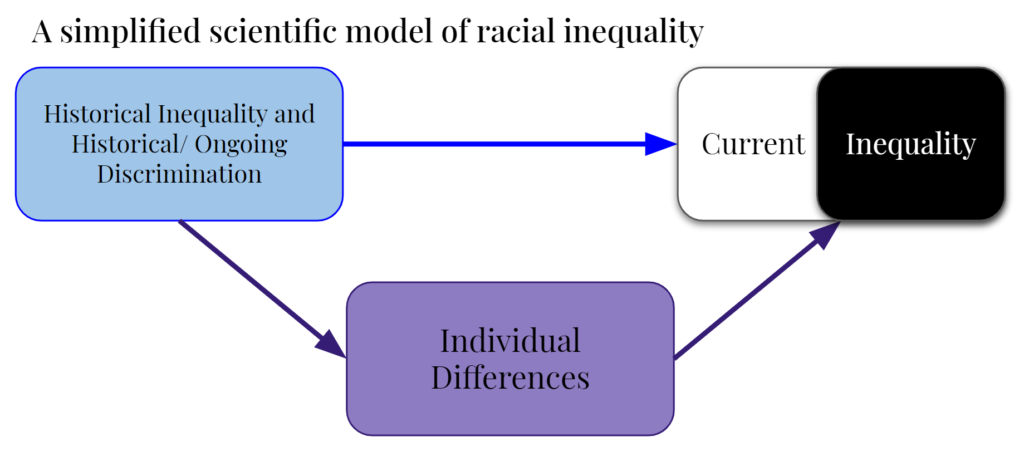

At the heart of this approach is seeing individual differences as a component of a recursive cycle, where disadvantage facilitates the development of tendencies (such as a lack of belonging and the resulting vulnerability to failure or academic disengagement) that maintain or exacerbate disadvantage (which reinforce negative tendencies, etc). This cycle means that something like feeling you don’t belong is both a result and cause of racial inequality. This theory has led to wonderful scientific findings! For example, there was a 2009 intervention where students participated in a series of writing tasks to reflect on their values. In the task, students wrote about the personal importance of a self-defining value. This simple task in early seventh grade resulted in Black students having a stronger belief in themselves to fit in and succeed in school. These changes in the psychological orientation of students accounted for a significant decrease in the white/Black achievement gap by 8th grade graduation. There are plenty more examples of these types of interventions throughout psychology.

Thus, the conservative viewpoint is partly correct: choices, values, and behavior can lead to differences in terms of who gets into college, who succeeds academically, and who becomes successful. I suspect most liberals and academics would agree with this view but do not agree that this view should be used to dismiss discrimination and systemic problems. Racial differences in choices, values, and behavior may help maintain and exacerbate racial inequality but we need to ask, “where do racial differences in choices, values, and behavior come from?” The academic answer is that they emerge from contexts that are deeply related to discrimination in the past and in the present. Furthermore, by understanding the origins of racial differences in behavior we can more effectively develop interventions that mitigate these differences. But it’s important to note that interventions like the belonging intervention are attempts to address the symptoms of racial inequality; they do not deal with inequality at it source by ameliorating historical injustice or correcting current discrimination (as found in the hiring and housing studies discussed above).

In summary

Taking in all of the research discussed above, the role of discrimination in racial inequality has such a strong foundation in historical and empirical facts that denying the role of discrimination is to depart from a scientifically informed view. On the other hand, the notion that racial inequality is at least in part due to values, behavior, and choices is true to some extent as well. Indeed, this is at the heart of much of the research about how to close achievement gaps between Black and white students. However, the perspective found in academic journals is communicated in quite different terms compared to some conservative arguments. Scientists and historians know that racial disparities in values, behaviors, choices, and even culture have emerged in a continually discriminatory environment with intergenerational disadvantages that maintained racial inequality. My investigation suggests that a science-based model of the causes of inequality accepts both narratives as partly true and not mutually exclusive.

If someone uses the argument that individual differences in values, culture, or behavior accounts for racial disparities as a way to deny discrimination as a cause, they are no longer aligned with the scientific evidence; we know discrimination is real, is currently happening, and is part of the story of inequality. If they cite individual differences as a way of blaming disadvantaged groups for their own disadvantage, they are also not aligned with the scientific evidence; we know that many of these individual differences emerge from a historical and current context of inequality that Black communities have had minimal control over. On the other hand, if someone is denying any role for individual differences, they have also departed from the relevant science.

In this era of extreme partisanship and misinformation, it is more important than ever to ensure that our ideological perspectives are tempered and informed by the scientific evidence. The causal story behind racial inequality is extremely complex; I have barely scratched the surface in this article. We should leave no tool out of our tool box in order to solve the problem of racial inequality. We need people to investigate and study discrimination, the individual differences that account for inequality, the contexts that give rise to the individual differences, and the systematic forces at work. We also need science-based interventions and advocacy to address both the causes and symptoms of racial inequality. The resulting research should guide our thinking about these topics and help us find solutions. That means admitting the interplay between contexts and choices, between decisions and discrimination, and between history and the here-and-now.

Peer edited by Melody Kessler and Rachel Ernstoff

Follow Manuel Galvan on Twitter and read more of his writing on the Pipette Pen and on his blog, The Science of Social Problems.