How many times per year do you normally visit the doctor? If you’re like the average American, you visit the doctor about 2.8 times per year. But during these visits, does your doctor ever discuss your diet or provide advice for improving your nutrition?

If you’re like most people, you rarely discuss nutrition with your doctor. However, two recent scientific studies (study 1, study 2) point out the importance of talking about nutrition when you’re at the doctor’s office.

Globally, our diet is unhealthy and causes disease

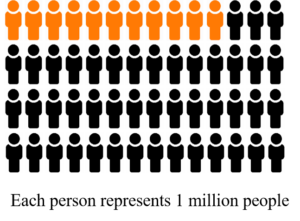

Most people around the world do not eat an optimally healthy diet. Although there are many opinions on what constitutes a “healthy diet”, most scientists and nutritionists agree that a healthy diet includes lots of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, healthy fats, nuts, seeds, and legumes and excludes processed foods, excess sodium, trans fatty acids, and red meat. A recent study quantified just how bad the world’s nutrition is. In 2017, approximately 11 million deaths (~20% of the 56 million deaths that year) were attributed to suboptimal diets. (Of note is that this study only considered nutrient intake and did not factor in undernutrition or obesity.) The number of deaths linked to poor nutrition is even higher than the number of global deaths caused by tobacco smoking, which accounted for ~13% of deaths in 2017.

Even worse, another 255 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) were lost in 2017 due to poor diet. For an individual, one DALY is a year of healthy life that is lost because of a preventable disease. For example, imagine that the average healthy lifespan of a population is 80 years. In this scenario, a person who is diagnosed with cardiovascular disease at age 75 and then lives to 80, has lived only 75 healthy years, and 5 DALYs have been lost to the disease.

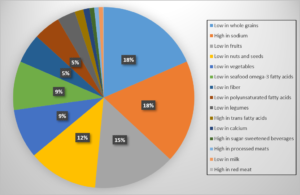

So what are these suboptimal nutritional choices? The researchers of the study looked at 15 diet-related risk factors for poor health. These includeed diets low in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts/seeds, milk, fiber, calcium, seafood, or polyunsaturated fats, as well as diets high in red meat, processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages, trans fatty foods, or sodium.

However, not all of these risk factors had the same impact on health. Approximately 8 million of the 11 million total deaths ascribed to food were attributed to high intake of sodium, low intake of whole grains, and/or low intake of fruit. Although a few countries (mostly in Africa) consumed the ideal amount of sodium, not one single region of the world that was studied met the recommendations for whole grains or fruits.

These dietary risk factors reduced life span and increased disease risk in people regardless of their age, sex, or sociodemographic status, demonstrating the impact of poor nutrition across all boundaries.

The medical system has not trained your doctor on nutrition

Part of the reason that people do not eat healthy food is because most people are confused about what to eat. In fact, a study from 2018 finds that 80% of Americans say that they see conflicting information about what they should eat. When someone is confused about what they should do for their health, who is the easiest person to access for a question? Usually, the answer is their doctor. However, another recent study shows that physicians around the world are not adequately trained in nutrition, and some physicians do not feel confident to counsel their patients on nutrition.

When students enter medical school, they show great interest in being trained in nutrition. However, by the time they graduate, their interest has declined greatly. This is partially due to the low amount of time spent on nutrition training during a medical degree. A survey from 2008 revealed that doctors in the U.S. get an average of 20 hours of training in nutrition across all 4 years of their medical training, and this number has not changed in recent years. This is in contrast to the approximately 27,000 hours spent on non-nutrition topics. Furthermore, nutrition education is not emphasized during the overall medical training, and medical students are not instructed in methods of integrating nutrition into their medical practice. In fact, about half of medical students fail a test on basic nutrition.

The lack of physician training in nutrition leads to physicians’ lack of confidence in offering quality nutrition advice to their patients. This lack of confidence leads to less discussion of nutrition with patients, which is to the patients’ detriment. When doctors discuss diet with their patients, their patients are more likely to make smart dietary choices, which can improve their health and prevent disease.

It is not necessary for doctors to be experts in nutrition to help their patients. Adequate training in nutrition would enable doctors to provide basic advice to patients as well as to know enough to refer patients who need further help to health professionals with more nutrition training (dietitians, nutritionists, etc.).

What can we do about it?

As scary as this information may seem, there are things that we (individuals, doctors, researchers, and/or policy makers) can do to improve the world’s nutrition.

- Concentrate on achieving a diet that is healthier across multiple dimensions, such as increasing fruit and whole grain intake while decreasing salt intake, without focusing on fad diets.

- Ask your doctor for nutrition-based steps you can take to improve your health.

- Advocate for increased training in nutrition for all medical professionals.

- After further training in nutrition, increase nutrition counseling for patients, especially for patients who have diseases with a clear nutrition-disease link, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and certain cancers.

- Identify and validate reliable biomarkers of nutrition status and design better methods of dietary assessment so that we can better understand and improve the world’s nutrition.

- Perform more intervention studies and randomized controlled trials to determine the impact of diet on health. Many current studies are observational, which are great for describing the problem, but are often less useful for investigating potential solutions.

- Write policies that target evidence-based dietary risk factors (such as promoting a higher intake of whole grains and fruit and limiting salt intake).

- Write policies that consider the impact of the food industry on people’s dietary choices, since the food industry is often neglected in dietary interventions.

- Consider setting global standards for training doctors in nutrition so that doctors can meet patients’ needs for nutrition counseling.

Although improving the world’s diet and changing medical training may seem like insurmountable tasks, their importance is underscored by the fact that improving the world’s diet has the potential to prevent or delay 1 in 5 deaths. As individuals, we can first make changes to our lives, and then we can advocate for improvements in physician training, medical nutrition counseling, measurements of global nutrition, and nutrition policies.

Peer-reviewed by Fanting Kung and Samantha Stadmiller