If you’ve been on social media recently, you might have come across a viral lyric that’s resonating with millions: “We’ve never really studied the female body.” Across TikTok, Instagram, and other platforms, people are using this audio to call out long-standing gaps in medical research due to the historical exclusion of women in studies. One particular medical gray area is Autoimmune disease. There is no specific known cause, nor cure, yet 80% of the patients are women.

Autoimmune disease background

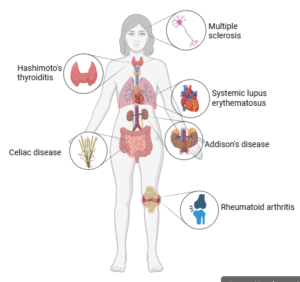

Autoimmune disease refers to the immune system mistakenly attacking healthy cells in the body instead of protecting it. There are several triggers that may cause a person to develop an overactive immune system. These diseases are chronic conditions, which means the symptoms must be managed for a lifetime.

Medical Gaslighting

It is often medically difficult to diagnose these types of disease because they are invisible illnesses, and may take up to 4 years to officially diagnose. Although there are medical reasons that autoimmune diseases are hard to diagnose, it’s hard to ignore the fact that women often get misdiagnosed or undiagnosed due to gender bias. This disbelief in women’s symptoms is so common that it has a name, “the trust gap,” and it dates back centuries. From ancient times to the 20th century, women’s health complaints were frequently written off as “hysteria.” Many autoimmune symptoms in women are dismissed by medical professionals as menstrual or mental health related. Since many symptoms of autoimmune diseases overlap with other conditions, healthcare professionals are quick to label women’s symptoms as stress or anxiety, attributing ambiguous symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, digestive trouble, or inflammation to psychological distress. As a result, many women feel confused and helpless because they have to battle these symptoms constantly, just to be told “it’s all in your head” or “it’s just your period.”

In fact, a research study from 2018 uncovered hidden gender bias in research papers. They found that men in chronic pain are more likely to be perceived as “stoic” (a virtue of someone who endures and does not complain) while women in similar situations tend to be labeled as “emotional” or “hysterical” and even accused of “fabricating the pain.” But the trust gap is just one piece of a much larger puzzle. Another barrier is the “knowledge gap,” the result of a deep systemic practice of excluding women from participating in research. Before the NIH inclusion policy was written into law in 1993, women weren’t even required to be included in clinical trials. As a result, we lack a strong foundation for understanding how diseases impact women differently. Inevitably, traditional medicine has also evolved to better fit the male anatomy. Moreover, a recent Stanford Medicine-led study noted that a molecule called Xist, which is produced by every cell in a woman’s body, is a trigger for autoimmunity. Yet for decades, we have only used a male cell line as the standard model.

Gender disparity–Societal/gender roles leads to decreased access to healthcare:

There are significant gender disparities when it comes to healthcare access.

The 2024 North Carolina Health Disparities Analysis Report found that rural women experience higher rates of disease and diagnostic delays due to limited access to healthcare. North Carolina Institute of Medicine has shown that there are more people in NC without health insurance, and women are disproportionately impacted by this.

Key Points

Autoimmune diseases can take years to diagnose, which may lead to worse health outcomes and emotional damage for patients. Events like Autoimmune Disease Awareness Month are important for spreading the word, but awareness alone isn’t enough. People also need good treatment options, education about their disease, and financial help so they can actually get the care they need. Future research should look at how race, ethnicity, gender, and life changes all play a role in how these diseases start and progress, especially for women. Future studies should be more inclusive and take a more holistic view, which could close the gaps in care and give people with autoimmune diseases a fair chance at better health.

Written by: Chandana Herlekar and Kelsey Zuniga Diaz

Edited by: Raeanne Lanphier and Elizabeth Abrash