No one ever wants the day to come: you’re told that your normally happy, goofy pup has been acting lethargic and out of character because they have a brain tumor. You’re devastated. These kinds of brain tumors are considered incurable. How absolutely unfair that such a random stroke of biological fate would single out your canine best friend. But what if there was a way for your pup, in the middle of the worst time of their life, to get a chance at a potentially life-prolonging treatment and to help other dogs and humans who suffer from the same disease?

This is the purpose of a clinical trial funded by the National Institutes of Health at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), the Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine, and two other sites. The trial focuses on the treatment of high-grade glioma, or HGG, a devastating brain tumor that is estimated to affect approximately 17,000 new patients this year. Because dogs and humans get HGG at around the same rate and their tumors look very similar, Dr. Renee Chambers, the lead investigator on the study, had the idea to test an exciting new treatment for the disease in both dogs and humans at the same time. And thus, CANINE (Canine ImmunoNEurotherapeutics) was born. Let’s take a deeper look at why HGG is so devastating in dogs and humans, how this new treatment works, and how investigators at UAB and Auburn are bringing people and their furry best friends together to give brain tumor patients a better shot at survival.

High-grade glioma, a devastating and incurable disease

Gliomas are tumors that arise from glial cells, or the cells in the brain that are not neurons. These tumors can be located just about anywhere in the brain. The ones labeled “high grade” (HGG) are so insidious because individual tumor cells can invade the normal brain. These sneaky, havoc-wreaking cancer cells are too small to be seen by a surgeon, so it’s impossible to remove them completely. Although people with HGG are normally first treated with surgery to remove their tumor, we know that some of these invisible cells are almost always left behind, where they can grow back into tumors later. To attack these tiny invaders, patients are usually treated with cancer-killing chemotherapy or radiation after their surgery. However, HGG cells have developed many ways of resisting typical cancer treatments, so patients’ tumors almost always come back. Unfortunately, even with this aggressive treatment, typical survival time for an HGG patient is only 12-15 months. There are some environmental or hereditary factors that have been linked to an increased risk of developing HGG, but scientists don’t know for sure what causes these tumors, making it difficult to develop new treatments for them. Researchers regularly use brain tumor samples from human and canine patients to try to figure out how these tumors happen and how to better treat them.

Cancer-killing viruses: a new frontier in HGG treatment

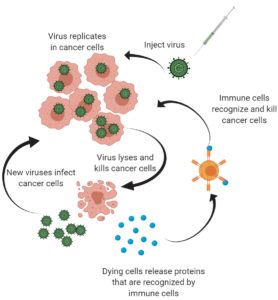

One of the most promising treatments for HGG to come on the scene in the last few years is the use of cancer-killing, or oncolytic, viruses to kill the leftover invading tumor cells after surgery. Normally, viruses cause damage to your body by infecting cells, using their machinery to make lots of new viruses, and then bursting the cells open, releasing more virus and starting the cycle over again. In oncolytic virus therapy, scientists hijack this cycle to create viruses that preferentially infect and kill cancer cells while leaving healthy, normal cells alone. The virus used in the CANINE trials is a modified version of a herpes virus called M032 developed at UAB in the lab of neurosurgeon Dr. James Markert. This virus has shown promise in destroying cancer cells grown in the lab as well as in mice with brain tumors, but with fewer of the harmful effects on healthy tissue seen in traditional chemotherapy or radiation treatment. With these promising data in mind, it was time to move on to clinical trials to see if M032 could help humans and dogs.

A new leash on life for canine and human glioma patients

That’s where the CANINE trial comes in. Run by Dr. Chambers along with Auburn veterinarians Drs. Amanda Taylor and Amy Yanke, and Auburn veterinary pathologist Dr. Jey Koehler, this trial recruits dogs that have been diagnosed with HGG and are out of options. Typically, these dogs are short-nosed breeds like boxers and French bulldogs, who are at an increased risk for developing brain tumors over their longer-snouted counterparts. Drs. Taylor and Yanke, who specialize in canine brain surgery, remove the visible tumors and then later inject the M032 virus directly into the hole that is left behind. The idea is that the modified virus will seek out and destroy the hiding leftover cancer cells that make HGG so deadly. While in the trial, the pupper patients have access to cutting edge medication and treatments to help manage their symptoms, and the best part is that their owners don’t pay a dime for their best friends’ care. Owners are responsible for the costs associated with HGG diagnosis, but the NIH funding for the trial takes care of the rest. While dogs are being treated at Auburn, human HGG patients are undergoing the same surgery and virus injection at UAB. The idea, the study investigators say, is that since dogs and humans both spontaneously develop these brain tumor and share a lot of environmental influences, like our houses, our sleep schedule, and in some cases, our food, studying brain tumor treatment in both species at the same time could yield better insights into how the tumors arise and how the treatments work.

While the CANINE trial will ultimately benefit human HGG patients, the study authors stress that the pups stand to gain just as much. Unlike a lot of animal research, the study protocol is carried out on pet dogs who have developed devastating tumors, not laboratory animals that the disease has been introduced into for the purpose of the study. The dogs are receiving state-of-the-art treatment and veterinary care, and what we learn from their treatment can be used to help future canine brain tumor patients. So while we know that all doggos are good (that’s just a scientifically proven fact), the pups in this trial are downright superheroes. During the hardest days of these dogs’ and owners’ lives, they are contributing to translational science that will hopefully help thousands of other pups and humans down the road.

For more information on the CANINE trial, click here. For information about enrolling a pupper patient in the trial, click here.

Peer edited by Eliza Thulson and Jenna Beam