I was sitting at my kitchen table with a scattered mess of textbooks and notes studying for my first graduate school final. The white board was filled with incoherent scribbles of chemical structures and electron arrows. I had hit a wall, and all the thoughts of self doubt and inadequacy played on an endless loop through my brain: “I’m not as smart as everyone else, I don’t deserve to be here, and now they will really know I’m a fraud.” I ended up passing the courses, so clearly I am smart enough to be at UNC. However, those negative feelings kept creeping back up to the surface over the years, no matter how many P’s I earned in my courses, positive reviews I received from my PI, or even fellowship awards I won. The nagging feeling of inadequacy remained! It turns out this emotion has a name: impostor phenomenon, aka impostor syndrome.

I was sitting at my kitchen table with a scattered mess of textbooks and notes studying for my first graduate school final. The white board was filled with incoherent scribbles of chemical structures and electron arrows. I had hit a wall, and all the thoughts of self doubt and inadequacy played on an endless loop through my brain: “I’m not as smart as everyone else, I don’t deserve to be here, and now they will really know I’m a fraud.” I ended up passing the courses, so clearly I am smart enough to be at UNC. However, those negative feelings kept creeping back up to the surface over the years, no matter how many P’s I earned in my courses, positive reviews I received from my PI, or even fellowship awards I won. The nagging feeling of inadequacy remained! It turns out this emotion has a name: impostor phenomenon, aka impostor syndrome.

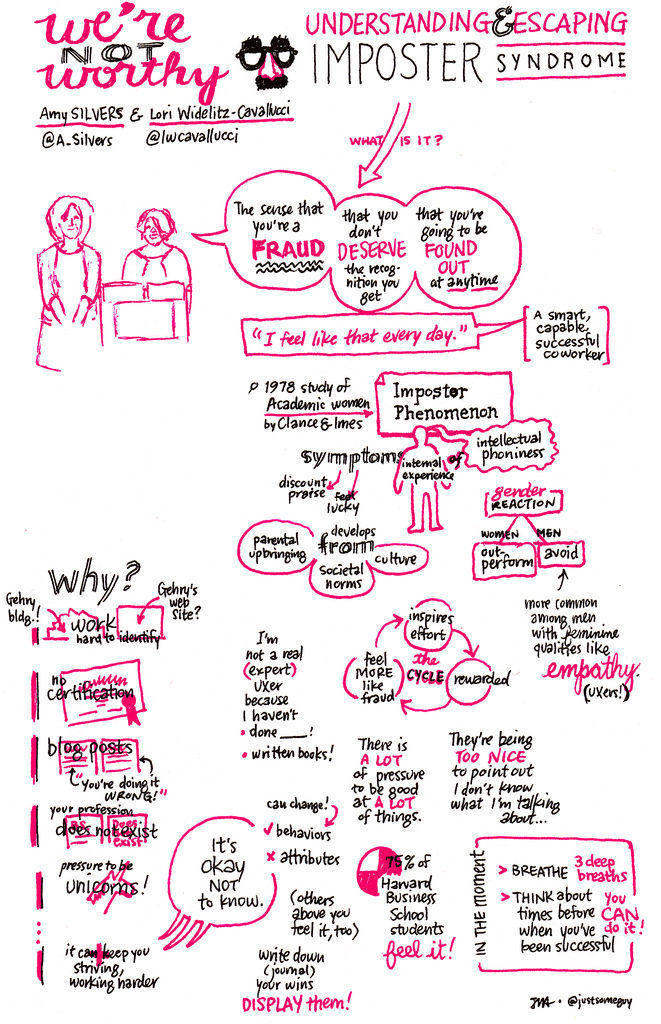

Impostor syndrome is described as feelings of perceived inadequacy even when there is plenty of evidence otherwise. Many people struggle silently with feelings of chronic self-doubt, intellectual fraudulence, anxiety, and depression. These can become so severe that it stifles performance in graduate school or the workplace. Ironically, it’s usually successful people that suffer from impostor syndrome; even acclaimed celebrities and high profile business executives are not immune. They will attribute their success to luck or generosity of others – anything but their own hard work and skills. This is extremely common for many professionals and graduate students. These high achievers set unsustainable, high expectations on their work and when the standards are not met, allowing feelings of deficiency to creep in.

The impostor phenomenon was first studied by Suzanne Imes and Dr. Pauline Clance, who saw a strong link between the impostor syndrome and perfectionism. Imes posits that impostor syndrome could result from growing up in households that place an exuberant emphasis on achievement. This resonates with my personal experience. In my family, we got A’s. Not A-’s. Only A’s were acceptable, and before long, I became overtly self-critical when I didn’t get an A on a test or even a homework assignment. It’s no wonder why self-worth becomes directly tied to achievement. Students either fear their work won’t be perfect and procrastinate, or they develop obsessive work habits, spending more energy than necessary. These unhealthy study habits, developed in high school, can become firmly seeded during undergraduate careers. In intensive graduate programs, that sense of achievement, once drawn from grades, gets drawn from the success of research projects.

Graduate and professional students spend years struggling to learn extremely difficult material, overcoming failed experiments, and (hopefully) becoming experts in highly specialized fields. It is easy for students to lose their sense of personal identity as they become expert scientists. Perfectionism and attention to detail are described as skills by many successful scientists, but these skills can also be holding us back in many ways if we succumb to the Impostor Monster.

Do others see your impostor syndrome?

Most of the time, the people suffering from impostor syndrome hide their symptoms extremely well because they are afraid of being exposed as a fraud. If impostor syndrome becomes too bad, others will start to notice your lack of self-confidence and increased self-doubt. This can be problematic during performance evaluations, job interviews, and committee meetings and can start to negatively impact your life other than just emotionally.

How could your impostor syndrome be holding you back?

Impacts on graduate school:

- The fear of being exposed as a fraud can lead students to take less risks in lab. Students would be afraid of an experiment failing and having to tell their boss they failed, over time leading to less creative research and lower productivity.

- Holding back on submitting publications or proposals because they might not be absolutely perfect.

- Negative self talk can lead you to think you’re not good enough, then you don’t do your best work which, by default, reinforcing the negative thoughts.

- Constantly comparing yourself to others only feeds the impostor monster and wastes energy that could be better spent elsewhere.

Impacts on professional career:

- Not taking ownership of personal accomplishments can result in not getting a promotions, awards, and recognition.

- Miss opportunities for new experiences: lowering career goals to match feelings of being unqualified. For example, deciding not to pursue a tenure-track position at a research intensive university because of the feelings of fraudulence and inadequacy.

- Work way too hard to make up for your “deficiencies” which can make you more likely to burn out.

So what can we do about this impostor syndrome?

Most people struggle with this their whole lives, but there are ways to keep it from running the show.

Put your impostor syndrome in perspective: Identify your feelings and do a reality check. Assess whether your feelings of incompetence are exaggerated.

Remind yourself what you are good at: Determine what your skills are and what you have accomplished so far. Remember, getting into graduate school itself is a major accomplishment!

Write down the compliments that you receive: On days when you’re struggling with negative thoughts, reading the positive thoughts others have about you will boost your self-confidence. Also, try to accept compliments with a simple “thank you” rather than discounting them.

Build a support group of trusted friends and family: There’s a good chance that most of your peers are going through this too and think that they are also the only one suffering.

It’s been a few years now since my first graduate school finals, but my impostor syndrome still resurfaces from time to time. I still struggle everyday with setting realistic standards for the amount of work I can accomplish and avoid my excessive perfectionist tendencies. When I start to think “I’m not good enough,” I stop and remind myself what I’m good at and how much I have improved as a scientist since starting graduate school. Don’t let your impostor syndrome run wild and limit your future success in life.

Peer edited by Tom Gilliss and Kelsey Noll.

Follow us on social media and never miss an article: