As most chemists probably know, a couple of weeks ago the scientific journal Angewandte Chemie published an opinion piece written by Tomas Hudlicky on the current state of the field of organic synthesis. The article did not recap the new reactions and methods in synthesis that had been developed over the past few decades, but instead focused more on societal and cultural factors that shape the field. Two of the factors Hudlicky discussed, “diversity in the work force” and “transference of skills”, made waves in the chemistry community, and not in a good way. Essentially, Hudlicky writes that preferential hire of women and minorities have, by default, disadvantaged other populations (read: white men) and that the deliberate effort to hire diverse candidates instead of the most qualified ones is compromising scientific progress. He also likens the relationship of a graduate student to their PI as an apprentice to a master, and that students’ “submission” to their “master” is rarely attainable in this day and age, as “many students are unwilling to submit to any level of hard work demanded by professors”. Oof.

Although the article was retracted only hours after publication, the damage had already been done; respected PIs from across the nation denounced the article and 16 members of the journal’s international advisory board, which included multiple Nobel laureates, resigned from their positions. Angewandte Chemie has since released an apology stating they intend to both increase diversity in their editorial and advisory boards and investigate their peer review process, as people have rightly brought up concerns on the integrity of the latter given that an article like this was published. Media coverage of this incident has, deliberately or not, vilified Hudlicky for his statements, but Hudlicky has commented that he has received many emails in support of his article. To the best of my ability, I’d like to unpack some of his arguments as objectively as possible, as well as the issues in the sciences that this publication brings to light.

On diversity in the sciences. Hudlicky claims that over the last several decades, diversity initiatives have come to the forefront of hiring practices. He is correct; many companies and universities are making deliberate efforts to hire or accept women, minorities, and people in lower socioeconomic classes. He then argues that these diversity programs are hurting the rate of scientific advancement since hiring based on merit alone is no longer the priority. His opinion, presumably, is that we should strictly be hiring candidates based on their qualifications for the job, regardless of race. In other words, if the best applicant is black, great – if they’re white, also great – it shouldn’t influence the hiring process.

This is an argument I’ve heard before from friends and family – that race shouldn’t be used favorably or discriminatorily. This argument doesn’t seem advertently racist, but here’s the problem with it – our society has historically and systematically favored white men. Historically, it has been easier for white men to vote, get access to higher education, own property, etc. Because of this, if you were given an applicant pool of ten people and were tasked to pick the best one, most of those applicants would be white, simply from how society operates. Picking the best applicant in the pool would most likely mean picking a white applicant, perpetuating a lack of diversity in the workforce. Thus, it’s important to have ‘diversity hires’ so that eventually the demographic of that applicant pool naturally reflects the demographic of the modern United States. Even if that candidate is slightly less qualified, in the vast, vast majority of cases, any missing skills can be learned in a short period of time. If I were talking to Hudlicky directly, I could imagine him arguing that he shouldn’t have to invest any extra time to train a new hire, to which I would ask, “as a professor, why are you so resistant to teaching?”

Still, investing extra time to train a new hire could validate Hudlicky’s claim that diversity hires are handicapping scientific progress. And sure, the effort spent teaching skills could have theoretically been put towards making the next big synthetic breakthrough – but realistically, what is the chance of making that breakthrough? Scientific progress is an unknown variable; it could be as substantial as the discovery of penicillin, but it could equally be, and more commonly is, something much less significant. As scientists, we are trained to make a hypothesis, collect quantitative, tangible evidence, and use this evidence to determine whether our hypothesis is correct. But you can’t tangibly measure what progress is theoretically lost by diverting effort to something like training a slightly less qualified new hire. So, scientifically, if Hudlicky’s hypothesis is not quantifiable, it really isn’t much of a hypothesis at all; instead, it is a weak attempt at justifying racial prejudice in the name of science.

On the relationship between a grad student and their PI. I’d be remiss to say the average relationship between a graduate student and their PI has not changed significantly over the last several decades. In the past, PIs had much more freedom to treat graduate students how they pleased; they could (and probably often did) routinely require grueling hours, police lab notebooks, and microaggressively dismiss ideas and hypotheses from their students. And complementarily, graduate students might have viewed this as a rite of passage for earning a doctorate, one that thickens their skin and prepares them for a career in the sciences. This, I imagine, is where Hudlicky is coming from in his sentiment that grad students are now “unwilling to submit to any level of hard work demanded by professors”. He may believe this rite of passage trains graduate students to be unabashedly critical and entirely devoted to their work; this process helps make great scientists.

To me however, this argument loses its merit when Hudlicky advocates to continue teaching classical organic chemistry skills solely because they are tried and true. He mentions several synthetic and analytical techniques that are rarely used in chemistry today – because importantly, most, if not all, of them have been replaced by more advanced methods. Taking extra time to learn old techniques could hinder scientific progress (shock, horror) for minimal practical gain, so his resolve to teach somewhat antiquated chemistry skills reveals a possible ulterior motive behind treating a graduate student like an apprentice – one that echoes, I had it this way, so you should too. To this, I’d say that just because my organic chemistry lab professor used to pipette dichloromethane (a toxic chemical) with his mouth – true story – doesn’t mean I should too. Just because these methods were indispensable to organic chemistry during the 20th century, doesn’t mean they might not be now. And most importantly, just because graduate students used to tolerate a much more demanding and sometimes degrading lab environment, doesn’t mean they should now.

On the culture of racial exclusivity in the sciences. We all likely agree that the sciences, especially physical sciences, have long been dominated by white men. Despite strides to increase diversity in scientific fields, this longstanding history of racial and sexual homogeneity runs deep, and sadly, so too does the intent to keep it. If nothing else, the writing, editing, and publishing of Hudlicky’s article gives us a very tangible way to see this racial exclusivity at work.

Let’s first consider the polarizing language Hudlicky used in the “transference of skills” section of his article, namely the ‘submission’ of ‘apprentices’ and the ‘demands’ of ‘masters’. Some of my colleagues have given Hudlicky the benefit of the doubt, saying that his language was, at worst, incredibly tone-deaf and terrible timing in the recent wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. But if you think about it, the apprentice/master analogy just doesn’t work for science. Apprenticeships are most found in trade professions, such as smithing or carpentry, because the skills an apprentice must learn from their master have not appreciably changed over time. Science, however, is constantly evolving; doctoral programs literally require you to publish work that no one has previously done to receive your degree. How can this be accomplished if all a graduate student can do is recapitulate the knowledge of their PI? There’s also no such thing as a ‘science master’, because we often study the unknown, and it’s impossible to be an expert on things yet to be discovered. Why then, use this language?

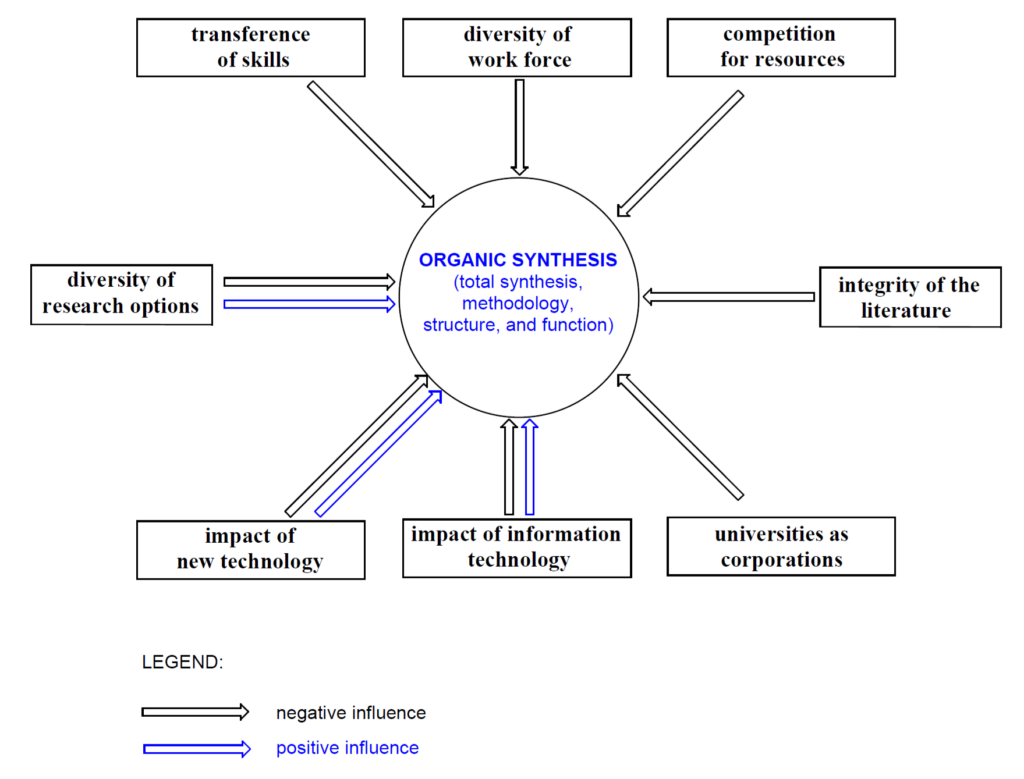

Then, there’s the issue of the figure. Hudlicky chose one figure to accompany his article (Figure 1, shown above), which originally was printed in his book, The Way of Synthesis, in 2007. The figure shows a series of factors and indicates their net influence, positive or negative, toward the field of organic synthesis; note that “diversity of work force” is shown as a negative influence. To be clear, I don’t believe that Hudlicky views diversity in the workforce as an inherently bad thing. Rather, as I discussed above, I believe that he views the deliberate effort to increase diversity as detrimental. I’ve unpacked why I still disagree with that statement, but importantly, it took me hours, if not days, of critical reflection to come to that conclusion. Most people have not given Hudlicky that luxury; they see this article and its accompanying figure, and immediately vilify him for his statement.

A colleague of mine has placed a degree of blame on the reader, then, for not taking the time to analyze and truly consider what Hudlicky meant. While I do agree that social media encourages the fast consumption of information, Hudlicky could have easily taken steps to prevent the vast ‘misinterpretation’ of his article. Hudlicky has previously mentioned that his words are being taken out of context, but in writing this paper, he himself took this figure out of a book he previously wrote, giving the reader little choice but to interpret it out of context. He also chose to make it the sole figure of the paper, in effect making it a graphical abstract. Those who read scientific papers know that a graphical abstract is key to both grabbing the reader’s attention and explaining the paper’s essence in a small space. Those who write scientific papers know that a lot of care and consideration goes into designing these figures, and that papers and their figures go through multiple drafts before submission. At best, Hudlicky did not go through this process, resulting in the submission of an ignorant, poorly conceived opinion piece. But I find it hard to believe that the ill-fitting nature of the apprentice/master analogy and the provocative figure are just a series of accidents; I believe Hudlicky was deliberate in his actions.

It is alarming that a professor at an accredited institution felt comfortable submitting this piece for publication. This in and of itself shows just how deep the sentiment of racial exclusivity is rooted in the field of chemistry. It is even more alarming, however, that his paper made it through the review process of a reputable journal and was published. What I sincerely hope is that the editors assigned to this paper were busy, or lazy, or otherwise occupied, and didn’t read it before greenlighting it for publication (which is still, extremely worrisome). But what I fear is that the editors read this paper and agreed with it, or at least felt no duty to dispute it – because this would mean that racial prejudice is so ingrained in scientific culture that it has become the status quo, and that individual scientists have either accepted this, are apathetic towards this, or are scared to speak up for fear being ostracized. This reality is not only disheartening but discouraging for aspiring scientists who aren’t white men (of which I am neither). It indirectly, but very loudly, says you aren’t welcome here.

Final thoughts. Scientists often pride themselves in being critical, deliberate, and objective, but too frequently, this means that scientists tend to be one of the last groups to engage in the discussion of qualitative issues, like those in social justice. The apathy toward discussing racial issues is only further exacerbated by the fact that most people in the sciences are white men, characteristics that have allowed them to navigate their careers without experiencing discrimination first-hand. Consequently, I sometimes feel that minorities in the sciences are burdened with a catch-22. On one hand, it is our duty to facilitate productive conversations about race in the scientific field; on the other hand, we should be satisfied just to have the opportunity to be working towards a doctoral degree in the sciences – something very few people, let alone women or minorities, get to do.

Hudlicky’s paper should never have been published. But since it has, I am at least grateful that it has provided an opportunity for scientists to speak about racial inequity in a lens they can more easily understand. In my relatively short time being in the field, I have already seen so much ignorance and passivity about race from the scientific community; I myself have sometimes been complicit in letting this racist culture continue. To those still reading, I hope this piece will encourage you to think actively on your contributions toward bridging the racial gap in the sciences, and I hope you feel compelled to act on these thoughts. Racial prejudice is still alive and well in the sciences, and Hudlicky’s paper is just one tangible example of it. One thing is clear: all of us – regardless of race, sex, or gender identity – have work to do here.

Peer edited by Keean Braceros and Jamshaid Shahir

This is a really great piece and thank you for taking the time to write it.

I have only one comment, and it’s that I think there may be a misunderstanding of what an apprenticeship is. Having done similar things in the arts and having known people who have gone into vocational training, it should not be just revomitting what the master has done. Likewise, as you say, it shouldn’t involve any “submission” to the “master” (ew I feel gross just typing that). One is a master of their trade, not their apprentices. Part of being a master is keeping up with the times. With this understanding, I would say that this is an apprenticeship.

I bring this up since it feels like an unnecessary jab at trade skills, which has some (likely unintended on the part of the writer) classist undertones. Everything else, this article is great! I remember trying to read Hudlicky’s piece and thinking to myself, ew no thank you and I hope angewandte chemie either learns a good lesson from this or goes under.

I’ve reflected some more, and I think the fact that the writer misconstrued vocabulary of apprenticeship, does speak volumes about how Hudlicky was using it– I fear I may have denied that emotional truth* in my original comment and apologize if that was the case**. Indeed, it seems to me to reinforce exactly what the writer says– that these racial, gender and class privileges protect people who aren’t truly the most adept while also blocking out those who are or have the potential to be.

Again, thank you for taking the time to write this. I hope the fact that it has stuck with me speaks to how great it is!

——-

* I use ’emotional truth’ as something which is valid since it strikes at the undertones and subtext, not in the usual dismissive sense I see in academia and stem fields in particular. Tbh, I didn’t finish Hudlicky’s article (didn’t need to, imo) and it’s been taken down (also imo, not bad thing); I believe the author’s takeaway and thank her for her service.

** This is the internet so I don’t know, and it’s not really for me to decide.